The Christmas at Sea; A Bittersweet Story of Child Migration

Written by Anthony Chambers

It was just beginning to become cold on that winter's day in December in 1951. The leaves were long fallen, but their delicate brown and crumpled skeletons lifted up easily with the chilling wind as they fell and drifted from the bank into the Grand Union Canal whose muddy waters flowed into the village of Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire, England. The narrow Grand Union Canal had begun its journey in London, just twenty miles away, yet to the small boy on its banks, engrossed in his own imaginative world, life in this market town was truly a million miles from the devastation and destruction still evident from the last World War in the great city.

The brisk, almost icy, breeze blew along the old rutted, uneven tow path, which still showed the wear from a hundred years ago when horses pulled the longboats. But the little boy, Anthony, Tony to his family and friends, never noticed the cold wind as he continued playing his solitary game of pirates and scampering over the slippery wooden lock gates on the canal.

Tony's family, like most of the village, were poor, yet they were in a special position as opposed to their less fortunate neighbors. The family resided in a lovely, old, detached home with a secluded front flower garden which was tended lovingly by his grandmother. The family also kept an allotment where Tony's grandfather grew their vegetables. His grandfather was a "Brickie" who worked reeling bricks for the many new homes under construction. Masses of Londoners sought to escape the constant noise and confusion of reconstruction in an attempt to erase the memories of years of destruction through escaping to the outer villages.

Tony, nine years old, lived in this rambling old home with his grandparents, his mother and an aunt. This happy little boy had no idea that tensions brewed within this family. The unspoken stigma of a child born out of wedlock placed an uncomfortable pressure upon the relationships in the home. When Tony's mother announced her pregnancy, an undeniable and unshakeable wedge had began to form between her and her parents.

Tony had never known his father, but this was no hardship. Due to a close knit family, including cousins nearby, he had never missed a biological father. He was also a joyful child, who spent his boyhood in dreams and wonder. He would spend entire afternoons wandering the old market town, marching and running through the gentle, grassy fields and steep, wooded hills engaged in his own world of imagination.

Unbeknownst to him, Tony's seemingly idyllic existence reached its end during this cold December. Tony's mother, due to family problems and tensions, was forced to remove herself from the home and go out to work. To an woman without marketable skills, that meant, more than likely, a job as a live-in housekeeper. But no domestic servant would be allowed to keep her illegitimate child in the home of her employer, so she took the only available option open to her in those days. She approached the local authorities to see if there was a way for Tony to be properly cared for temporarily. It would only be until she could get on her feet.

Just weeks earlier, his mother had met earlier with the child welfare agency. They told her of a great opportunity that was available to her son. They smiled as they told her of how he would be happier under the child emigration scheme to the British Commonwealth countries. There, under the warm sun and healthy open spaces, Tony would be given a more secure environment than any which she could offer him in the damp, English air and tough economic climate.

All she had to do was sign. Just sign her name saying he could participate. That was all she had to do and Tony would be taken to the land of milk and honey.

With that trembling signature, and without realizing the conditions, Tony's mother signed her parental rights away. With just a pen's stroke, she lost her chance to bring him back to England once she regained her ability to support him. As she walked out of the agency's door, she believed that Tony would only be obtaining schooling and foster care until she could have him back with her in a home she would provide. She could confidently believe he would be safe; he would be healthy; and he would be back.

That wintery December afternoon, though, Tony ran to his home as usual having slain the pirates and capturing his imaginary castle. Sometime later, he was told that he would be leaving. He would be going on a holiday, a wonderful adventure, where he would be traveling on a great steamship to a new home in a strange and wonderful land.

Far from sad and filled with a sense of discovery, Tony left his home and family later that month on dreary, cold, early evening. His large suitcase was carried by his uncle and Tony walked with his mother down the path from the house to a narrow foot bridge where he crossed the canal and away from the village where he had been born. Away from the only home he had ever known.

The little trio reached the train station. For Tony, it was pure magic. He had often watched the steam trains seemingly fly by his village, but, being poor, he had never actually ridden one. The world raced by as they sped to the great city of London. In awe as he reached the busy train station, he excitedly climbed aboard a double decker bus.

They reached a large, rambling hotel where his mother and uncle gave him a quiet goodbye. No tears, he remembered later. Perhaps those tears would be shed later, when she was alone. Despite her sudden onset of "cold feet," she knew she had to obtain a job and a place to live before she could arrange to bring him back. It was only temporary, she could keep telling herself, it was only temporary. Private regrets and consequences would follow her for the rest of her life but she always tried to believe that mantra.

Because it was late in the evening when they reached the hotel, Tony did not meet the rest of the party with whom he would be traveling. Those children and teenagers were already tucked away in their rooms, so Tony was taken to a room where he would be staying by himself. The kindly porter gently told him to ring a bell if there was anything he needed, then the he closed the door and was gone.

For the first time in his nine years, Tony was alone. He had never been alone before. He had no idea what to do or what to ask for if he did ring that bell. He could not remember the last time he had eaten, yet he remained quiet, unable to find the courage or determination to ring the bell. Confused and disoriented, he then spent that half of that night wandering the long, scary hotel corridors and stairwells on his own.

During his travels through the old hotel, he had become enraptured with the central foyer goldfish pond, letting the hours slip by watching the fish dart about in the water. The officials in his party found him still there the next morning. Upon his discovery by the relieved guardians, Tony was ready to go. He believed that his adventure had begun with the fascination he had found in that fishpond.

He was introduced to his group of 17 children and teenagers, along with the two supervisors, a man and a woman. Tony was the second to the youngest boy in the group of mixed children and three teenaged girls. Once he had his belongings and the group were reunited, they were placed into taxis and taken to the St. Pancras station where they would catch the 10:45 boat train to the shipping docks of Tilbury. They would be boarding the steamship Rangitoto, its name originating from "Rangi", a New Zealand Maori god, as well as a sleeping volcano in the Auckland harbor. There the little group would join other individuals and families, emigrating for as many reasons as there were people.

The train ride from London to Tilbury was exhilarating. It was exciting to be with the other children, who were also giddy from the adventures they would have, and with the older teenagers traveling alongside them, it became even more thrilling.

Once in Tilbury, the group queued up with all of the ship's passengers. Tony stayed on deck with some of the older children and watched as the ship pulled away from the dock, gliding down the Thames River past the lights of South End. It was there, in the foggy night, that Tony, through fear or confusion, began to escape into the safety of memories which would become hidden in his subconscious, creeping through sporadically throughout his life. Somehow, he managed to make it to his six-birth cabin where he slept with five others and the male supervisor. He tried once to to search the ship for his mother, even though he knew inside she was gone, just in case.

Their adopted guardians were kind to the group of children. They were New Zealanders who were returning home who had been conscripted, of sorts, by the agency handling the children's migration on behalf of the government. Over the weeks that followed, the children clung to the couple, bonding with them in a sort of ragtag family.

The migrant families were another story. He would see them staring and often heard them saying about the little group "you poor kids with no mums or dads." But I have a mum, he thought, resenting their clouded concern.

The ship sailed past the Channel Islands into the heaving dark green seas of the Atlantic. The children had finally settled into shipboard life and, even if their legs were a bit wobbly from the persistent seasickness, they found themselves have a wonderful time. There were good meals and bunk room pillow fights. There were the kind supervisors to make sure they bathed and brushed their teeth and to offer comfort and affection. The pain of homesickness gave way to the enjoyment of life at sea.

Time slowed to a crawl as the ship continued its way across the ocean. It seemed to take ages to arrive in the Caribbean. The first port of call was the tiny island of Curacao, part of the Netherlands Antilles. Tony finally found his sea legs as they reached these calmer waters. As they finally neared his first landmass, he saw with amazement the oil refineries on shore intersected with scattered palm trees.

As soon as they came into port, the party arranged to go into the capital city of Willemstad. Tony felt a thrilling chill as he set foot on a foreign shore for the first time. Upon touching the sandy earth, it was relief to feel the hot dry air and stand once again upon solid ground.

Tony had become close to one of the boys in his group. With this new found friend by his side, Tony and the group walked toward the town. The day was one of sheer pleasure for active, healthy children and passed quickly. The day complete, the little group gingerly walked back to the ship, when, suddenly, his friend nudged Tony. He looked up and saw a field of pineapples along the road. The two boys, snickering, sneaked into the fields and picked two of the strange fruits, when they were astonished to discover the farmer chasing after them with a big knife. The boys made a quick getaway back to the ship.

The ship departed, traveling into the Panama Canal zone. Passengers went ashore at Colon in the Port of Cristobel, and Tony was taken aback at the site of jungle bound lakes and wild, tropical looking streets. Within the town, dirty water would be thrown from the upstairs windows to the streets below. These sights would remain with Tony through his life so strongly that, though he did not know it at the time, he would return one day of his own accord.

Later on the ship, as they traversed the Canal, they passed American naval vessels, and crossed into the Pacific Ocean. To Tony this truly was a brave, new world. England and Hertfordshire seemed a faded memory for him now.

As the Rangitoto crossed the equator, it seemed the the rambunctious boys grew ever more active. While pillow fighting in the their lower deck bunk room, Tony sprained his ankle. Not long after, while helping with the stacking and unstacking of the portable chairs for the ship's cinema, he fell into a stack of the chairs as the ship lurched. This injury caused the ship to stop mid-ocean and set the serious break in his wrist. He was taken around the decks with his already sprained ankle to have a cast fitted to his arm from his right wrist all the way up to to a fix set elbow.

Despite his injuries and raucous enjoyment of friends, Tony was one of the ship's darlings. He knew how to charm the Captain, his officers and the crew. Because he had been grounded from his injuries, he took time to learn more about the floating home he had been residing within. Instead of running amuck, he stood at the ships railing and marveled at the sea, looking for land. Instead of racing along the corridors and ramps, he began to study the curvature of the ocean from a large world map which showed the ship's course.

One morning, as the children awoke as usual on their floating home, the ship's Purser gave out a "merry Christmas to all."

That night, the seas seemed silent and the Southern Cross shimmered int he distanced as if an angel had appeared over the large ship.

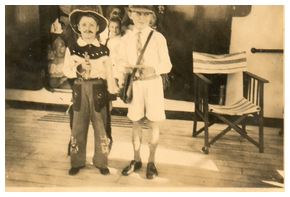

At the Christmas party that night, Tony watched as Santa himself, dressed in his red regalia and long white beard, appeared out of a tiny door in the huge single smokestack. All of the children received presents for the festive occasion. An enormous Christmas dinner complete with a fancy dress party for the children. Tony dressed as a Royal message boy with a cookie cap and his famous smile. He was surprised to learn he had actually won first prize in the costume contest by delivering a telegram to the Captain.

Carol singing, colored lights and the magic of a warm tropical night at sea.

But back in England, Tony's mother would not be in Christmas spirit. There was a sense of loss within this family, and for his mother, the holiday would never be the same.

Christmas complete, the ship continued on its journey, anchoring at Pitcairn Island. Tony stood amazed at the huge, long boats which rowed out to the ship. The Pitcairn islanders climbed aboard to sell souvenirs and talk about their isolated life. Entranced by the islanders, he looked, still in wonder, out on the murky water to see fish flying into the air like aircraft. It was surreal, unbelievable and wonderful.

As they moved on, suddenly a new land seemed to arise before his very eyes. "Aotearoa" the land of the long, white cloud was coming up to meet them as it had done to the early Maori voyagers when the legend said "they fished the land from the deep, blue sea." The Maori had come in their stout canoes from Polynesia, and now Tony was arriving with his group in their own stout canoe named as those canoes had been so long ago.

The children were called into the spacious lounge where they had played by moving the soft chairs to form hide-outs. All of the group were given a briefing on what to expect in this new country called New Zealand. Tony listened in amazement of the active volcanoes, earthquakes, hot mud pools, millions of sheep, and native forests called the "Bush." He sat wide-eyed hearing of the original people who did a war dance called "Haka", of rugby, its heroes dressed in black. He learned of the farms which were everywhere on the two main islands, of low type houses and spread out cities. They told him of the beaches and the snow-capped Alps. The New Zealanders on the ship had said it was the best country in the world, and at the moment this wonderland was certainly that to these enthralled migrant children. With the New Year breaking, the children, now adjusted to the surety and sameness of life on a ship, wistfully gathered up their belongings from the galleys where they had felt at home. They stood and watched as the ship began slow steaming into a beautiful enclosed harbor with dark green forested hills on one side and funny little wooden houses with gaily painted rooftops in the steep hills on the other side.

His arm still encased in plaster, Tony went with the little group to the deck for a picture to document their time on the ship. To help support his arm, the porters sat him within a lifebuoy.

The children's guardians gathered their foster brood of jubilant youth together and told them not to wander off, because the officials would be coming on board when they docked. It was important that they stayed together so that they could be accounted for and documented to be sent to the various destinations to which they would be going.

Tony clung to the rails of the ship, goggle-eyed at this new land. He had not given any thoughts to the future. He had put aside the memories of his childhood in England. He felt as if he had been born anew. Ushered into a meeting room for the welfare officials, he was told of disembarkation. He was told to stay close to the rails of the gangplank as his new parents would be coming to claim him.

He began to escape into his familiar dreamworld, one where he could hide, but before he slipped away, he was suddenly shaken by a call out. "Tony, here is Mr. and Mrs. Chambers, come to take you to their home."

Suddenly warm and cuddly arms embraced him and a kind, loving face looked at him with a smile, telling him, "Call me mum and here is your new dad."

Together these three walked away and into a new life. Yes, there would be recriminations and guilt over the leaving of a mother in England. Yes, there would be confusion and frustration over the way Mother Britainnia chose to take those she did not wish to support and toss them to the winds where they may or may not find happiness in foreign worlds. Yes, there would be tears and bullies. But there would also be joy, happiness and friends for this British child migrant. There would be growing up, marriage and children. The story would continue.

But right now, on the warm January morning in 1952, thousands of miles from England, there was just a family, and a new beginning for Tony Chambers, the "boy in the Lifebuoy.'

The brisk, almost icy, breeze blew along the old rutted, uneven tow path, which still showed the wear from a hundred years ago when horses pulled the longboats. But the little boy, Anthony, Tony to his family and friends, never noticed the cold wind as he continued playing his solitary game of pirates and scampering over the slippery wooden lock gates on the canal.

Tony's family, like most of the village, were poor, yet they were in a special position as opposed to their less fortunate neighbors. The family resided in a lovely, old, detached home with a secluded front flower garden which was tended lovingly by his grandmother. The family also kept an allotment where Tony's grandfather grew their vegetables. His grandfather was a "Brickie" who worked reeling bricks for the many new homes under construction. Masses of Londoners sought to escape the constant noise and confusion of reconstruction in an attempt to erase the memories of years of destruction through escaping to the outer villages.

Tony, nine years old, lived in this rambling old home with his grandparents, his mother and an aunt. This happy little boy had no idea that tensions brewed within this family. The unspoken stigma of a child born out of wedlock placed an uncomfortable pressure upon the relationships in the home. When Tony's mother announced her pregnancy, an undeniable and unshakeable wedge had began to form between her and her parents.

Tony had never known his father, but this was no hardship. Due to a close knit family, including cousins nearby, he had never missed a biological father. He was also a joyful child, who spent his boyhood in dreams and wonder. He would spend entire afternoons wandering the old market town, marching and running through the gentle, grassy fields and steep, wooded hills engaged in his own world of imagination.

Unbeknownst to him, Tony's seemingly idyllic existence reached its end during this cold December. Tony's mother, due to family problems and tensions, was forced to remove herself from the home and go out to work. To an woman without marketable skills, that meant, more than likely, a job as a live-in housekeeper. But no domestic servant would be allowed to keep her illegitimate child in the home of her employer, so she took the only available option open to her in those days. She approached the local authorities to see if there was a way for Tony to be properly cared for temporarily. It would only be until she could get on her feet.

Just weeks earlier, his mother had met earlier with the child welfare agency. They told her of a great opportunity that was available to her son. They smiled as they told her of how he would be happier under the child emigration scheme to the British Commonwealth countries. There, under the warm sun and healthy open spaces, Tony would be given a more secure environment than any which she could offer him in the damp, English air and tough economic climate.

All she had to do was sign. Just sign her name saying he could participate. That was all she had to do and Tony would be taken to the land of milk and honey.

With that trembling signature, and without realizing the conditions, Tony's mother signed her parental rights away. With just a pen's stroke, she lost her chance to bring him back to England once she regained her ability to support him. As she walked out of the agency's door, she believed that Tony would only be obtaining schooling and foster care until she could have him back with her in a home she would provide. She could confidently believe he would be safe; he would be healthy; and he would be back.

That wintery December afternoon, though, Tony ran to his home as usual having slain the pirates and capturing his imaginary castle. Sometime later, he was told that he would be leaving. He would be going on a holiday, a wonderful adventure, where he would be traveling on a great steamship to a new home in a strange and wonderful land.

Far from sad and filled with a sense of discovery, Tony left his home and family later that month on dreary, cold, early evening. His large suitcase was carried by his uncle and Tony walked with his mother down the path from the house to a narrow foot bridge where he crossed the canal and away from the village where he had been born. Away from the only home he had ever known.

The little trio reached the train station. For Tony, it was pure magic. He had often watched the steam trains seemingly fly by his village, but, being poor, he had never actually ridden one. The world raced by as they sped to the great city of London. In awe as he reached the busy train station, he excitedly climbed aboard a double decker bus.

They reached a large, rambling hotel where his mother and uncle gave him a quiet goodbye. No tears, he remembered later. Perhaps those tears would be shed later, when she was alone. Despite her sudden onset of "cold feet," she knew she had to obtain a job and a place to live before she could arrange to bring him back. It was only temporary, she could keep telling herself, it was only temporary. Private regrets and consequences would follow her for the rest of her life but she always tried to believe that mantra.

Because it was late in the evening when they reached the hotel, Tony did not meet the rest of the party with whom he would be traveling. Those children and teenagers were already tucked away in their rooms, so Tony was taken to a room where he would be staying by himself. The kindly porter gently told him to ring a bell if there was anything he needed, then the he closed the door and was gone.

For the first time in his nine years, Tony was alone. He had never been alone before. He had no idea what to do or what to ask for if he did ring that bell. He could not remember the last time he had eaten, yet he remained quiet, unable to find the courage or determination to ring the bell. Confused and disoriented, he then spent that half of that night wandering the long, scary hotel corridors and stairwells on his own.

During his travels through the old hotel, he had become enraptured with the central foyer goldfish pond, letting the hours slip by watching the fish dart about in the water. The officials in his party found him still there the next morning. Upon his discovery by the relieved guardians, Tony was ready to go. He believed that his adventure had begun with the fascination he had found in that fishpond.

He was introduced to his group of 17 children and teenagers, along with the two supervisors, a man and a woman. Tony was the second to the youngest boy in the group of mixed children and three teenaged girls. Once he had his belongings and the group were reunited, they were placed into taxis and taken to the St. Pancras station where they would catch the 10:45 boat train to the shipping docks of Tilbury. They would be boarding the steamship Rangitoto, its name originating from "Rangi", a New Zealand Maori god, as well as a sleeping volcano in the Auckland harbor. There the little group would join other individuals and families, emigrating for as many reasons as there were people.

The train ride from London to Tilbury was exhilarating. It was exciting to be with the other children, who were also giddy from the adventures they would have, and with the older teenagers traveling alongside them, it became even more thrilling.

Once in Tilbury, the group queued up with all of the ship's passengers. Tony stayed on deck with some of the older children and watched as the ship pulled away from the dock, gliding down the Thames River past the lights of South End. It was there, in the foggy night, that Tony, through fear or confusion, began to escape into the safety of memories which would become hidden in his subconscious, creeping through sporadically throughout his life. Somehow, he managed to make it to his six-birth cabin where he slept with five others and the male supervisor. He tried once to to search the ship for his mother, even though he knew inside she was gone, just in case.

Their adopted guardians were kind to the group of children. They were New Zealanders who were returning home who had been conscripted, of sorts, by the agency handling the children's migration on behalf of the government. Over the weeks that followed, the children clung to the couple, bonding with them in a sort of ragtag family.

The migrant families were another story. He would see them staring and often heard them saying about the little group "you poor kids with no mums or dads." But I have a mum, he thought, resenting their clouded concern.

The ship sailed past the Channel Islands into the heaving dark green seas of the Atlantic. The children had finally settled into shipboard life and, even if their legs were a bit wobbly from the persistent seasickness, they found themselves have a wonderful time. There were good meals and bunk room pillow fights. There were the kind supervisors to make sure they bathed and brushed their teeth and to offer comfort and affection. The pain of homesickness gave way to the enjoyment of life at sea.

Time slowed to a crawl as the ship continued its way across the ocean. It seemed to take ages to arrive in the Caribbean. The first port of call was the tiny island of Curacao, part of the Netherlands Antilles. Tony finally found his sea legs as they reached these calmer waters. As they finally neared his first landmass, he saw with amazement the oil refineries on shore intersected with scattered palm trees.

As soon as they came into port, the party arranged to go into the capital city of Willemstad. Tony felt a thrilling chill as he set foot on a foreign shore for the first time. Upon touching the sandy earth, it was relief to feel the hot dry air and stand once again upon solid ground.

Tony had become close to one of the boys in his group. With this new found friend by his side, Tony and the group walked toward the town. The day was one of sheer pleasure for active, healthy children and passed quickly. The day complete, the little group gingerly walked back to the ship, when, suddenly, his friend nudged Tony. He looked up and saw a field of pineapples along the road. The two boys, snickering, sneaked into the fields and picked two of the strange fruits, when they were astonished to discover the farmer chasing after them with a big knife. The boys made a quick getaway back to the ship.

The ship departed, traveling into the Panama Canal zone. Passengers went ashore at Colon in the Port of Cristobel, and Tony was taken aback at the site of jungle bound lakes and wild, tropical looking streets. Within the town, dirty water would be thrown from the upstairs windows to the streets below. These sights would remain with Tony through his life so strongly that, though he did not know it at the time, he would return one day of his own accord.

Later on the ship, as they traversed the Canal, they passed American naval vessels, and crossed into the Pacific Ocean. To Tony this truly was a brave, new world. England and Hertfordshire seemed a faded memory for him now.

As the Rangitoto crossed the equator, it seemed the the rambunctious boys grew ever more active. While pillow fighting in the their lower deck bunk room, Tony sprained his ankle. Not long after, while helping with the stacking and unstacking of the portable chairs for the ship's cinema, he fell into a stack of the chairs as the ship lurched. This injury caused the ship to stop mid-ocean and set the serious break in his wrist. He was taken around the decks with his already sprained ankle to have a cast fitted to his arm from his right wrist all the way up to to a fix set elbow.

Despite his injuries and raucous enjoyment of friends, Tony was one of the ship's darlings. He knew how to charm the Captain, his officers and the crew. Because he had been grounded from his injuries, he took time to learn more about the floating home he had been residing within. Instead of running amuck, he stood at the ships railing and marveled at the sea, looking for land. Instead of racing along the corridors and ramps, he began to study the curvature of the ocean from a large world map which showed the ship's course.

One morning, as the children awoke as usual on their floating home, the ship's Purser gave out a "merry Christmas to all."

That night, the seas seemed silent and the Southern Cross shimmered int he distanced as if an angel had appeared over the large ship.

At the Christmas party that night, Tony watched as Santa himself, dressed in his red regalia and long white beard, appeared out of a tiny door in the huge single smokestack. All of the children received presents for the festive occasion. An enormous Christmas dinner complete with a fancy dress party for the children. Tony dressed as a Royal message boy with a cookie cap and his famous smile. He was surprised to learn he had actually won first prize in the costume contest by delivering a telegram to the Captain.

Carol singing, colored lights and the magic of a warm tropical night at sea.

But back in England, Tony's mother would not be in Christmas spirit. There was a sense of loss within this family, and for his mother, the holiday would never be the same.

Christmas complete, the ship continued on its journey, anchoring at Pitcairn Island. Tony stood amazed at the huge, long boats which rowed out to the ship. The Pitcairn islanders climbed aboard to sell souvenirs and talk about their isolated life. Entranced by the islanders, he looked, still in wonder, out on the murky water to see fish flying into the air like aircraft. It was surreal, unbelievable and wonderful.

As they moved on, suddenly a new land seemed to arise before his very eyes. "Aotearoa" the land of the long, white cloud was coming up to meet them as it had done to the early Maori voyagers when the legend said "they fished the land from the deep, blue sea." The Maori had come in their stout canoes from Polynesia, and now Tony was arriving with his group in their own stout canoe named as those canoes had been so long ago.

The children were called into the spacious lounge where they had played by moving the soft chairs to form hide-outs. All of the group were given a briefing on what to expect in this new country called New Zealand. Tony listened in amazement of the active volcanoes, earthquakes, hot mud pools, millions of sheep, and native forests called the "Bush." He sat wide-eyed hearing of the original people who did a war dance called "Haka", of rugby, its heroes dressed in black. He learned of the farms which were everywhere on the two main islands, of low type houses and spread out cities. They told him of the beaches and the snow-capped Alps. The New Zealanders on the ship had said it was the best country in the world, and at the moment this wonderland was certainly that to these enthralled migrant children. With the New Year breaking, the children, now adjusted to the surety and sameness of life on a ship, wistfully gathered up their belongings from the galleys where they had felt at home. They stood and watched as the ship began slow steaming into a beautiful enclosed harbor with dark green forested hills on one side and funny little wooden houses with gaily painted rooftops in the steep hills on the other side.

His arm still encased in plaster, Tony went with the little group to the deck for a picture to document their time on the ship. To help support his arm, the porters sat him within a lifebuoy.

The children's guardians gathered their foster brood of jubilant youth together and told them not to wander off, because the officials would be coming on board when they docked. It was important that they stayed together so that they could be accounted for and documented to be sent to the various destinations to which they would be going.

Tony clung to the rails of the ship, goggle-eyed at this new land. He had not given any thoughts to the future. He had put aside the memories of his childhood in England. He felt as if he had been born anew. Ushered into a meeting room for the welfare officials, he was told of disembarkation. He was told to stay close to the rails of the gangplank as his new parents would be coming to claim him.

He began to escape into his familiar dreamworld, one where he could hide, but before he slipped away, he was suddenly shaken by a call out. "Tony, here is Mr. and Mrs. Chambers, come to take you to their home."

Suddenly warm and cuddly arms embraced him and a kind, loving face looked at him with a smile, telling him, "Call me mum and here is your new dad."

Together these three walked away and into a new life. Yes, there would be recriminations and guilt over the leaving of a mother in England. Yes, there would be confusion and frustration over the way Mother Britainnia chose to take those she did not wish to support and toss them to the winds where they may or may not find happiness in foreign worlds. Yes, there would be tears and bullies. But there would also be joy, happiness and friends for this British child migrant. There would be growing up, marriage and children. The story would continue.

But right now, on the warm January morning in 1952, thousands of miles from England, there was just a family, and a new beginning for Tony Chambers, the "boy in the Lifebuoy.'

Notes From the Author: As an adult, it was often difficult for me to understand why I had to be sent away, although, technically, without a biological father in the house for me or for the child of my aunt, it was considered a "broken home.” At first, it did not make sense to me why the agency to which my mother applied did not suggest sending me to another part of England. I was, however, to learn later that many children who went into care in England fared far worse conditions than I ever imagined. I had, it turned out, to have been very lucky indeed.

The group of children with whom I traveled were not war evacuees. Those children were given a return ticket booked for them depending on the results of the war in the proper time. The country cherished them. Our small group were socially stigmatized with a one way ticket--we could have been called "the No Pound Poms" as it cost our parents nothing--yet everything--to send us on this journey.

From the beginning of my time in New Zealand, life was happy for me. There were issues and problems, both those that most kids face growing up, but also the bullying and teasing of schoolmates as a “Pommie bastard." But generally the extended family and kind neighborly friends I had inherited with my loving new parents gave me a sense of security and stability. I was happy in my new, clean cut, sunny environment.

I became the legitimate son of a new mum and dad who were a kind and loving family. Parents who literally doted on me as a gift from England. Yet, the unfortunate consequence of this was that my birth mother went on to live a daily nightmare, always suffering with regret in the decision she made, or the decision which was imposed upon her, to give me up for adoption, and for me, fragmentation from my home and my birth family as well as great black holes in my memories. I became confused as to my real identity of family or allegiance to any nation.

Yet this confusion and the frustration helped me to find answers which allowed me a sense of re-conciliatory completion. It has also allowed me to be a the subject of a film (The Boy in the Lifebuoy) by Sejal Deshande of Mumbai (Bombay) India (who obtained her Masters degree from a Birmingham University. Her persistent and very professional efforts further helped me to unravel my fractured early life in the film story as well as its counterpart website: “The Child Migration Saga."

This, then, concludes a shortened version of the first chapter of my proposed book, The Boy in the Lifebuoy. There are seven more chapters which are available:

Chapter 2: This chapter deals with my growing up in NZ; family adaptation; legal adoption; schooling; trade work.

Chapter 3: My first return to search for lost birth roots via a six month Asian, Middle East & East/western Europe journey: (2nd migration)

Chapter 4: This chapter includes my settling back into England with a momentous visit to my birth family & home; work in London & Slough (close to Windsor Castle); meeting old down under mates (wild colonials all).

Chapter 5: This chapter includes meeting my future Spanish wife Maria in London; our wedding; and honeymoon in Spain; meeting Maria’s two different social class Spanish families, with last Spanish (adios) & English family goodbyes.

Chapter 6: Our journey to New Zealand via all Central America a three month journey (3rd migration at one time in an Indian dugout canoe en-route to down Under).

Chapter 7: Settling back into NZ with my new wife; raising our family with an internal shift from Christchurch to Auckland (4th migration); later Sydney Australia (5th migration); return to NZ (6th migration).

Chapter 8: Our last migration - a return to Europe and retirement; finely back into my old home town that sent me away (7th migration).

Afterword: The last years of caring for my birth mother, her saddened nightmare over at last; Maria’s serious illness; Hemel finally claiming its lost son in full reconciliation.

I would be pleased to offer via British Home Children Descendants a digest of the rest of the chapters if there is an interest to follow my story to its sad, but sweet, end.

Anthony (Tony) Chambers: pen name “Tonykiwi”… for (Anthony of the Commonwealth). [email protected]

The group of children with whom I traveled were not war evacuees. Those children were given a return ticket booked for them depending on the results of the war in the proper time. The country cherished them. Our small group were socially stigmatized with a one way ticket--we could have been called "the No Pound Poms" as it cost our parents nothing--yet everything--to send us on this journey.

From the beginning of my time in New Zealand, life was happy for me. There were issues and problems, both those that most kids face growing up, but also the bullying and teasing of schoolmates as a “Pommie bastard." But generally the extended family and kind neighborly friends I had inherited with my loving new parents gave me a sense of security and stability. I was happy in my new, clean cut, sunny environment.

I became the legitimate son of a new mum and dad who were a kind and loving family. Parents who literally doted on me as a gift from England. Yet, the unfortunate consequence of this was that my birth mother went on to live a daily nightmare, always suffering with regret in the decision she made, or the decision which was imposed upon her, to give me up for adoption, and for me, fragmentation from my home and my birth family as well as great black holes in my memories. I became confused as to my real identity of family or allegiance to any nation.

Yet this confusion and the frustration helped me to find answers which allowed me a sense of re-conciliatory completion. It has also allowed me to be a the subject of a film (The Boy in the Lifebuoy) by Sejal Deshande of Mumbai (Bombay) India (who obtained her Masters degree from a Birmingham University. Her persistent and very professional efforts further helped me to unravel my fractured early life in the film story as well as its counterpart website: “The Child Migration Saga."

This, then, concludes a shortened version of the first chapter of my proposed book, The Boy in the Lifebuoy. There are seven more chapters which are available:

Chapter 2: This chapter deals with my growing up in NZ; family adaptation; legal adoption; schooling; trade work.

Chapter 3: My first return to search for lost birth roots via a six month Asian, Middle East & East/western Europe journey: (2nd migration)

Chapter 4: This chapter includes my settling back into England with a momentous visit to my birth family & home; work in London & Slough (close to Windsor Castle); meeting old down under mates (wild colonials all).

Chapter 5: This chapter includes meeting my future Spanish wife Maria in London; our wedding; and honeymoon in Spain; meeting Maria’s two different social class Spanish families, with last Spanish (adios) & English family goodbyes.

Chapter 6: Our journey to New Zealand via all Central America a three month journey (3rd migration at one time in an Indian dugout canoe en-route to down Under).

Chapter 7: Settling back into NZ with my new wife; raising our family with an internal shift from Christchurch to Auckland (4th migration); later Sydney Australia (5th migration); return to NZ (6th migration).

Chapter 8: Our last migration - a return to Europe and retirement; finely back into my old home town that sent me away (7th migration).

Afterword: The last years of caring for my birth mother, her saddened nightmare over at last; Maria’s serious illness; Hemel finally claiming its lost son in full reconciliation.

I would be pleased to offer via British Home Children Descendants a digest of the rest of the chapters if there is an interest to follow my story to its sad, but sweet, end.

Anthony (Tony) Chambers: pen name “Tonykiwi”… for (Anthony of the Commonwealth). [email protected]