Except from the book, Stories Behind the Stones: The Churchyard and the Old and New Cemeteries at Great Yarmouth by Paul P Davies

Published in 2008 (ISBN-13: 978-0954450939, 540 pages):

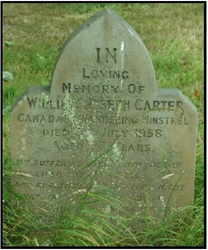

In 1958 William Carter was buried in his mother's grave in the New Cemetery, Great Yarmouth in accordance with his struct instructions, which he had drawn up a few years previously. He was 83 years of age. His directions stipulated that as his coffin was being lowered into the grave a record of George Beverly Shea singing He brought my Soul at Calvary should be played. A portable gramophone was brought to the graveside and was played as the Rev. A. Heigham read the commital service. George Shea was born in 1909 and sang at the services of the American evangelist, Billy Graham in the 1950's.

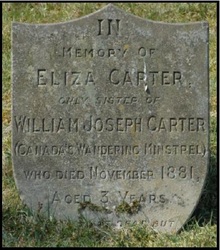

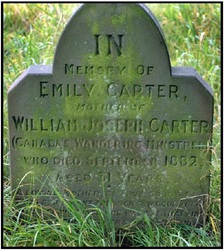

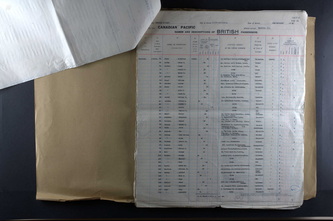

William Carter was born in Great Yarmouth in 1875 and led his adult life wandering around Canada. His mother died in 1882 and he entered a Dr. Barnardo's Home. One of his earliest memories was playing the mouth-organ and picking up tunes by ear. He never had a music lesson in his life. In 1899 he went to Canada with one of the groups of children, who were sent there from Dr. Barnardo's Homes, to be trained in farming. After fire destroyed his rented farm in Carrot River Valley in Saskatchewan in 1929, William Carter took to the road. He had lost all of his belongings, apart from his fiddle and his five whistles. He was forbidden to play on street corners and public places. Therefore, he gave impromptu recitals in offices, restaurants, pool rooms and wherever a few people were gathered. Usually a collection was made and he earned a few dollars.

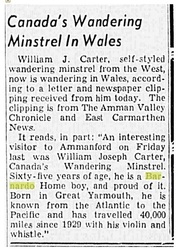

He crossed Canada four times playing a violin and penny-whistles. He claimed that the had wandered over 30,000 miles. His biggest audience was in Callender, Ontario, where he played to an audience of 8,000 people at a gathering to celebrate the birthday of the Dionne quintuplets. He had frequently broadcast from Western Canadian radio stations. His chief ambition was to return to England and, by saving coppers earned in the copper mining towns of Northern Ontario, he managed to pay his fare.

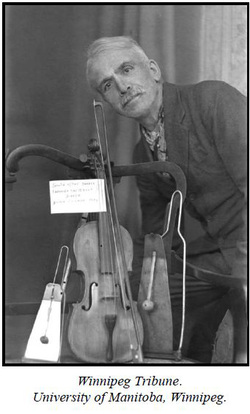

In 1935 William Carter was interviewed by the Winnipeg Tribune. Their journalist wrote:

William Joseph Carter is a wandering minstrel of these depression years. He has learned life's rich secret to live life carefully and happily with no anxious though for the morrow. He drifted into Winnipeg a few days ago. He played babbling melodies on his whistles and haunting lyrics on his violin, while office boys went into roars of laughter as he went into rhythmic ecstasies of movement. His iron-grey hair and chin-whisker, his face chestnut brown from life in the great outdoors, his brown eyes twinkling merrily, his incredible 60 year old vitality, his sturdy 62 inches of height combine to proclaim hi spiritual kinship with the troubadours and minstrels of Merrie England that was.

William Carter travels by train or bus, if he is in funds. Sometimes he is given lifts in cars, but mainly he walks. He has never been turned away from houses or farms hungry. People are glad to see the old fiddler. They find him happy and carefree. The whole day is one song of gladness to him. He likes to see people happy and to see the lines of care melt away from their faces as he plays.

In 1937 he was in Burnley, England where the local paper reported: 'this week a little elderly man with a goatee beard and a curious black lambskin hat is playing his metal whistle in the streets of Burnley. He stated his intention of trying his luck in this town for a week, having arrived here form Blackburn. Afterwards he intends to journey north to Scotland.'

In 1942, Winnipeg Tribune reported under the heading 'Top-Hatted Fiddler gets Nod from Genius':

one time prairie farmer and minstrel, W. J. Carter, who often wandered into Winnipeg with his fiddle tucked under a big bright smile has again broken into print, this time in England, his new stamping ground. The Nottingham Guardian had a story to tell of Canada's wandering minstrel with his black coat and battered top hat. This story concerns one of his proudest memories, an experience in Calgary in 193. William Carter related that he was doing his stuff when a man stopped to listen and then edged up to him and said 'why do you hold the fiddle like that'. I told him that it 'suited me and my public did not give a damn how I held her if the tunes pleased them'. The man then lent forward and said 'you're doing fine' and dropped a dollar bill into my hat. He then gave me his card and said 'beat it round to my hotel and tell them to fix you up'. That man was Fritz Kreisler, the famous violinist.

William Carter often returned to Great Yarmouth, though he died in an old men's home in Liverpool, where he had been living for some years. His will was made in 1953 and he lodged a copy, detailing his funeral wishes, at the Great Yarmouth Mercury's office, with the cemetery superintendent and with his solicitor. He left his scrapbook and three photographs to the Great Yarmouth Mercury to make use of them as they wished, and then they should be forwarded to the Winnipeg Tribune in Canada. The photographs were inscribed 'the last photograph of W. J. Carter'. In a note scribbled at the bottom of his will he stated that he had sent copies of it to newspapers in Winnipeg, Montreal and victoria, British Columbia. On the back of the will was written a number of verses and some prose, and some perhaps original and others from his scrapbook. After the payment of funeral expenses the residue of his estate was left to Dr. Barnardo's Homes

William Carter was born in Great Yarmouth in 1875 and led his adult life wandering around Canada. His mother died in 1882 and he entered a Dr. Barnardo's Home. One of his earliest memories was playing the mouth-organ and picking up tunes by ear. He never had a music lesson in his life. In 1899 he went to Canada with one of the groups of children, who were sent there from Dr. Barnardo's Homes, to be trained in farming. After fire destroyed his rented farm in Carrot River Valley in Saskatchewan in 1929, William Carter took to the road. He had lost all of his belongings, apart from his fiddle and his five whistles. He was forbidden to play on street corners and public places. Therefore, he gave impromptu recitals in offices, restaurants, pool rooms and wherever a few people were gathered. Usually a collection was made and he earned a few dollars.

He crossed Canada four times playing a violin and penny-whistles. He claimed that the had wandered over 30,000 miles. His biggest audience was in Callender, Ontario, where he played to an audience of 8,000 people at a gathering to celebrate the birthday of the Dionne quintuplets. He had frequently broadcast from Western Canadian radio stations. His chief ambition was to return to England and, by saving coppers earned in the copper mining towns of Northern Ontario, he managed to pay his fare.

In 1935 William Carter was interviewed by the Winnipeg Tribune. Their journalist wrote:

William Joseph Carter is a wandering minstrel of these depression years. He has learned life's rich secret to live life carefully and happily with no anxious though for the morrow. He drifted into Winnipeg a few days ago. He played babbling melodies on his whistles and haunting lyrics on his violin, while office boys went into roars of laughter as he went into rhythmic ecstasies of movement. His iron-grey hair and chin-whisker, his face chestnut brown from life in the great outdoors, his brown eyes twinkling merrily, his incredible 60 year old vitality, his sturdy 62 inches of height combine to proclaim hi spiritual kinship with the troubadours and minstrels of Merrie England that was.

William Carter travels by train or bus, if he is in funds. Sometimes he is given lifts in cars, but mainly he walks. He has never been turned away from houses or farms hungry. People are glad to see the old fiddler. They find him happy and carefree. The whole day is one song of gladness to him. He likes to see people happy and to see the lines of care melt away from their faces as he plays.

In 1937 he was in Burnley, England where the local paper reported: 'this week a little elderly man with a goatee beard and a curious black lambskin hat is playing his metal whistle in the streets of Burnley. He stated his intention of trying his luck in this town for a week, having arrived here form Blackburn. Afterwards he intends to journey north to Scotland.'

In 1942, Winnipeg Tribune reported under the heading 'Top-Hatted Fiddler gets Nod from Genius':

one time prairie farmer and minstrel, W. J. Carter, who often wandered into Winnipeg with his fiddle tucked under a big bright smile has again broken into print, this time in England, his new stamping ground. The Nottingham Guardian had a story to tell of Canada's wandering minstrel with his black coat and battered top hat. This story concerns one of his proudest memories, an experience in Calgary in 193. William Carter related that he was doing his stuff when a man stopped to listen and then edged up to him and said 'why do you hold the fiddle like that'. I told him that it 'suited me and my public did not give a damn how I held her if the tunes pleased them'. The man then lent forward and said 'you're doing fine' and dropped a dollar bill into my hat. He then gave me his card and said 'beat it round to my hotel and tell them to fix you up'. That man was Fritz Kreisler, the famous violinist.

William Carter often returned to Great Yarmouth, though he died in an old men's home in Liverpool, where he had been living for some years. His will was made in 1953 and he lodged a copy, detailing his funeral wishes, at the Great Yarmouth Mercury's office, with the cemetery superintendent and with his solicitor. He left his scrapbook and three photographs to the Great Yarmouth Mercury to make use of them as they wished, and then they should be forwarded to the Winnipeg Tribune in Canada. The photographs were inscribed 'the last photograph of W. J. Carter'. In a note scribbled at the bottom of his will he stated that he had sent copies of it to newspapers in Winnipeg, Montreal and victoria, British Columbia. On the back of the will was written a number of verses and some prose, and some perhaps original and others from his scrapbook. After the payment of funeral expenses the residue of his estate was left to Dr. Barnardo's Homes