Edward Jones

Memoirs of a Barnardo Child

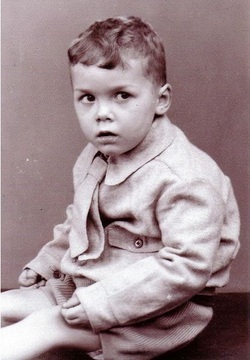

Photo: 1937 Edward at 3 years 6 months.

In April of 1934, when Edward was just three months old, his mother died. On that same day, in the very same family home, her brother also died. They lived on Crichton Street, right on the boundaries of Clapham and Battersea, England. After the death of his mother, Edward was taken to the Barnardo's Hawkhurst Babies Castle. Although Barnardo's was a charity, his father had to pay to have him there.

At three and a half, the day this photo was taken, Edward was fostered out to the Gostling family in Stowmarket, Suffolk. Here Edward would live until he was nine years old. His years spent with the Gostling family were happy ones. Sadly his foster mother suffered a stroke and became unable to care for Edward. He was sent to live with an older couple who had five Barnardo children already with them.

At nine years of age, Edward was put to work at this home doing milk rounds with another Barnardo child named Frank. Together they would rise at 5:30 am , walk a mile to the dairy and work their way back home measuring milk out on the door steps. When they were finished, they grabbed their school things and off to school they went.

In the summers they would have double summertime, meaning it was light until 10 pm. After school they would have bread and jam, then went to work in the fields, singling beets, which meant where there was five beet growing you would remove four and leave the strongest one. They would do this until it was nearly dark.

One Saturday, when the boys were out working a milk run, Frank was helping the milk man by collecting money. Unknown to Edward, Frank was helping himself to some money. When the boys were done work they walked home. The milk man, who had a bike, had already been there and had told the older foster couple about the missing money. When Edward, first inside, entered the home the man trapped him inside. With no explanation at all, he beat Edward with a stick for the theft. At church that Sunday, a relative of Edward's previous foster mother saw all the bruises and reported it to his Barnardo's visitor. Not long after that Edward was sent to Barnardo's Watts Naval Training Center. In 1947 Edward's name was down to be sent to Canada, it was only then that he learned that he actually had a father and two sisters who were alive and living in London.

In April of 1934, when Edward was just three months old, his mother died. On that same day, in the very same family home, her brother also died. They lived on Crichton Street, right on the boundaries of Clapham and Battersea, England. After the death of his mother, Edward was taken to the Barnardo's Hawkhurst Babies Castle. Although Barnardo's was a charity, his father had to pay to have him there.

At three and a half, the day this photo was taken, Edward was fostered out to the Gostling family in Stowmarket, Suffolk. Here Edward would live until he was nine years old. His years spent with the Gostling family were happy ones. Sadly his foster mother suffered a stroke and became unable to care for Edward. He was sent to live with an older couple who had five Barnardo children already with them.

At nine years of age, Edward was put to work at this home doing milk rounds with another Barnardo child named Frank. Together they would rise at 5:30 am , walk a mile to the dairy and work their way back home measuring milk out on the door steps. When they were finished, they grabbed their school things and off to school they went.

In the summers they would have double summertime, meaning it was light until 10 pm. After school they would have bread and jam, then went to work in the fields, singling beets, which meant where there was five beet growing you would remove four and leave the strongest one. They would do this until it was nearly dark.

One Saturday, when the boys were out working a milk run, Frank was helping the milk man by collecting money. Unknown to Edward, Frank was helping himself to some money. When the boys were done work they walked home. The milk man, who had a bike, had already been there and had told the older foster couple about the missing money. When Edward, first inside, entered the home the man trapped him inside. With no explanation at all, he beat Edward with a stick for the theft. At church that Sunday, a relative of Edward's previous foster mother saw all the bruises and reported it to his Barnardo's visitor. Not long after that Edward was sent to Barnardo's Watts Naval Training Center. In 1947 Edward's name was down to be sent to Canada, it was only then that he learned that he actually had a father and two sisters who were alive and living in London.

Edward's Memoirs of the Barnardo's

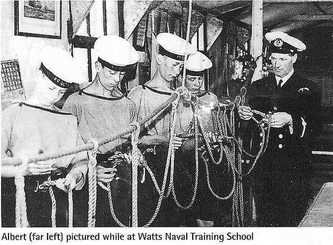

Watts Naval Training School 1945-1949

The officers at Watts School at that time were Captain Felton and Bert Busby. Mr. Haslem taught seamanship but he died soon after I got there and was replaced by Mr. Green. At the time Mr. Green seemed quite strict, but after I attended a reunion recently and had a long chat with him, he turned out to be such a nice man. He could have put plenty more of us on defaulters and let us off! He remembered nearly all of our names.My favorite Officer Sid Pointer, a lovely man, I always came top in signals. Perhaps that is why I still remember him well.

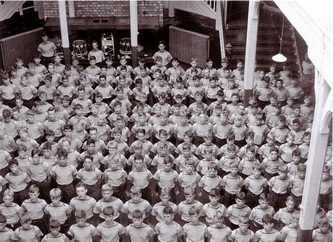

I don't think that many boys who left the school couldn't swim. I learned during my first summer I was there. There were a lot of boys who had never been in water before they went to Watts. Bert Busby and his wife used to teach us swimming. We never had swimming gear, so it was a bit embarrassing when you got to fourteen. We used to have a swimming gala once a year and they found us trunks for that.

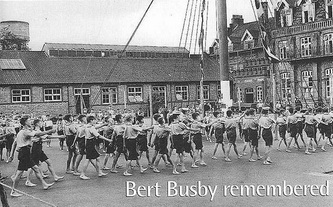

The teachers I can remember were the headmaster Wallis Hoskin, Mr. Kennerdy and the groundsman was Fred Hall. Fred gave me a cut down cricket bat for scoring a few runs in the cricket final! Bert Busby was the P.T.I. He also took us for boxing. Every year we had to box on an eliminator format. When slogger Harrington came back from the war he took over as he was an ABA champion pre-war.

I can remember being hungry most of the time. I think that when I first went to Watts it was very harsh. As I got older and more resilient it didn't worry me so much. In the summer we had siestas. We had to lay on our beds for an hour around one p.m. If you got off your bed, or made a noise, you were on defaulters!

I think we all suffered from a poor education. I can remember reading somewhere it was deliberate policy not to over educate us! When it came round to holiday periods we had to nominate someone who would take us. They used to put a list up outside the dining hall door whom had been accepted. As the end of July approached, and the boys names had gone up, there was a lot of tears near the dining hall door from those who hadn't been approved. I can also remember on the notice board, next to the holiday list, was Kiplings poem "If". The words seemed very appropriate, about being a man my son.

We were allowed to go to East Dereham once a month, on the train, from mid-day Saturday until about 6:30 when we got the train out of Dereham back to County Hall station. We had films Saturday night and whoever went to Dereham would bring back chips. Your friends would save you a seat back in the dining hall where they showed the films. When you first joined Watts you had to qualify, which entailed you learning the sailors hornpipe and learning to march. You were not allowed to go into Dereham until you were qualified in these two arts.

We had a swimming pool which was down by the river. In the summer, which began in April or May in those days, we had to go barefooted, except of Sundays, to get to the pool. We had to walk over a large area of loose asphalt and on approach to the pool the ground was covered with spiky gorse bushes. In April it was agony but by September your feet were so hard you could walk over broken glass!

While I was there we had a mass absconding, I think the boys were treated very harshly over that. When Captain Felton was in charge of the school it improved a lot. His wife was very nice as well. I can remember she used to read to the boys, mostly ghost stories! I am not sure but I think it was her that told us about the birds and bees. Living as we did, we only saw a girl about once a month! We used to go on cross country runs, mostly through young forest trees. Sometimes we would come across fields of carrots or beets and stop to eat a few, then continue on our run.

I can't remember any public floggings at Watts in my time there. The question about being in contact with people on the ourside, i used to write to my former foster mother, but Barnardo's had a policy of secrecy. I was thirteen before I found out that I had a father and two sisters living in London. My oldest sister tried for years to find out where I was.

The Bugler Calls - We all had a number, no name. They had a syster where the bugler called your number over the tannoy with a bugle call. If you didn't report to the quarter deck in a certain time, you had to give a good reason why. I think he had to go to more than one site to make his call.

On the subject of absconding, I think there was more then twenty-seven who escaped in the mass absconding as it has been reported, more like fifty. As to the subject of myself absconding, where would you go? We were all orphans or destitute children. The people I fostered with before I went to Watts treated me terribly, regular beatings with a stick, so that left them out.

We had a religious service every morning and evening. They had large hymn cards which were lowered down for us to follow. They always ended with the last verse of the naval hymn, Eternal Father. There was a plaque on the wall which said "fear God, honor your King", I'm afraid that by the time I left I didn't believe in God. Time was measured the same as on board ship, by ringing bells.

I don't think we were very well adjusted when we left Watts. I never felt I belonged anywhere until I married. I vowed I would never treat my children the way I had been treated. As to today generation, I think every previous generation think they had it tougher. I subscribe to service pals and people on there, who were in the forces in the eighties are complaining about the Squaddies of today! I think it has always been so. I personally think its just the luck of the draw who you are born to and the generation you live in.

If there is one item I would change about Watts, it would have been a better education.

Another item I remember is some of the boys were caught up in the scandal of immigration to Canada and Australia, which I think the court cases are still going on over. A friend of mine went to Canada and he wanted me to go with him, which I declined. I recently read Reg Trews article, Bakers Dozen on the web, made me cry my eyes out. I can remember some good days at Watts, I think the best moments were the nights before leave, when the school band played on the quarter deck. I finished my schooling but didn't want to go to ganges, so I stayed on at Watts for another nine months, as Commander Freeman's office boy.

I used to sit through and record all the punishment canings. All the items that were confiscated from boys, I used to take out of the locker and give back to them. They were harsh times. Remember tiller bonk?

If

by Rudyard Kipling

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too:

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or, being lied about, don't deal in lies,

Or being hated don't give way to hating,

And yet don't look too good, nor talk too wise;

If you can dream---and not make dreams your master;

If you can think---and not make thoughts your aim,

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same:.

If you can bear to hear the truth you've spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build'em up with worn-out tools;

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings,

And never breathe a word about your loss:

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: "Hold on!"

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings---nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much:

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds' worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that's in it,

And---which is more---you'll be a Man, my son!

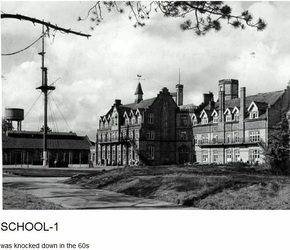

Please click on photo to see larger view