Dr. C. K. Clarke (Charles Kirk), 1857-1924

From "The Little Immigrants" by Kenneth Bagnell

Dr. C. K. Clarke, the superintendent of an asylum and a man whose name was to be given a generous place in Canada's medical history - Toronto's Clark Institute was named after him - once lectured to a group of students at Queen's College in Kingston and was warmly applauded as soon as he began to attack the inferiority of British waifs in Canada. "A pretty strong proof that the general public has not awakened to its responsibilities in regard to the problems of heredity" the doctor said, "is the fact that in Canada we are deliberately adding to our population hundreds of childdren bearing all the stigmata of physical and mental degeneracy. And this is being done openly and apparently with the consent of many who are really anxious to prove themselves philanthropists. I refer to the children who are brought to Canada in order to benefit themselves and the country. It is asserted that these children pass a medical examination and are invariably of healthy type. Could anything be more misleading, more untrue?". Dr. Clarke a man with large, bright eyes and a soft voice, went on recall that a few months earlier he had been on a train on which some of the children were being taken to the farms. For days afterward, he said, he was depressed, recalling the signs of degeneracy that were so obvious in the entire lot of them. "It is almost criminal neglect on the part of the authorities," he concluded to waves of applause, "to allow this sort of immigration to be permitted. And while some may assert that asylum and jail populations have not been materially increaded by such importations, they should remember that those who sow the wind shall reap the whirlwind. The next generation must be considered, bu the harvest has already commenced - a juvenile criminal here, an insane person there"

The next day, the Mail and Empire of Toronto declared that his address should be reprinted in every paper in the country.

The next day, the Mail and Empire of Toronto declared that his address should be reprinted in every paper in the country.

Dr. C. K. Clarke (Charles Kirk), 1857-1924

From: Archeion - Ontario's Archival Information Network

Charles Kirk (C.K.) Clarke, M.B., M.D., LL.D. was born in Elora, Ontario on February 16, 1857 and died January 20, 1924, in Toronto, Ontario. C.K. Clarke was the only son of Emma (Kent) Clarke and Lieutenant-Colonel the Honourable Charles Clarke, Member of the Legislative Assembly, 1871-1894, Speaker of the Assembly, 1880-1885, and Clerk of the Assembly, 1901-1907. C.K. had two older sisters—Jennie and Emma. Jennie married a son of Dr. Joseph Workman, Superintendent of the Toronto Asylum. Emma married Dr. William Metcalf, who had been medical assistant to Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke, and, from 1882 until his violent death at the hands of a patient in 1885, was Superintendent of Kingston Asylum. Clarke married Margaret DeVeber Andrews in Toronto, October 1880 (deceased December, 1902). They had four sons and two daughters: Charles Marshall Clarke (1881-1940), Emma deVeber (Goldie) Clarke (1882-?), Margery Workman Clarke (1884-?), Harold Metcalf Clarke (1885-1925), Herbert Secord Clarke (1887-1938) and Eric Kent Clarke (1894-1958). Clarke’s second wife was Theresa Gallagher, whom he married in August 1904 in Kingston, Ontario. His residence in Toronto was at 55 Wellesley Street.

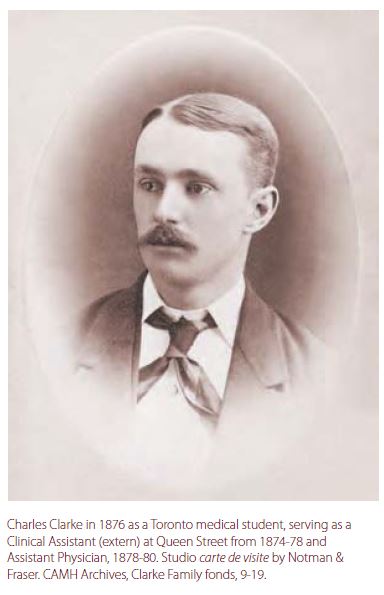

C.K. Clarke was educated at Elora High School and Toronto University (M.B., 1878; M.D., 1879). He received an honourary LL.D. from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario in 1906. He was Clinical Assistant to Dr. Workman at the Toronto Hospital for the Insane, 1874-1878, and Assistant Physician of the same institution from 1878-1880. He was Assistant Superintendent at the Hamilton Hospital for the Insane, 1880-1881, Assistant Superintendent at Rockwood Hospital for the Insane, Kingston, 1881-1885, under Dr. Metcalf, Superintendent, Rockwood Hospital, Kingston, 1885-1905, Superintendent, Toronto Hospital for the Insane, 1905-1911 (replacing Dr. Daniel Clark), Medical Superintendent, Toronto General Hospital, 1911-1917 and Medical Director, Toronto General Hospital from1917-1918. Clarke first became a member of the University of Toronto’s teaching staff in 1889, while still the Superintendent of Rockwood.

He was also Professor of Mental Diseases at Queen’s University until coming to Toronto. In 1906, Clarke became the first Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto. He later served as Dean of the Medical Faculty at the University of Toronto from 1908-1920.

On March 15, 1887, in connection with the Hospital for Insane, Kingston, the medical staff gave the first of a series of lectures to the student nurses. This was the earliest attempt in Canada to provide formal psychiatric training for nurses caring for the mentally ill. The first class graduated in 1889. One of the students, Miss Theresa Gallagher, eventually became Head Nurse and Dr. Clarke’s second wife. Also at Rockwood, Clarke introduced an infirmary for acute cases, occupational therapy, established non-restraint and had convalescent homes and outdoor treatment of cases of tuberculosis put into existence. He steadfastly tried to destroy any resemblance between an asylum and a prison, and would eventually succeed in reducing the stigmatic designation by having Ontario’s asylums renamed ‘hospitals for the insane’. Clarke was appointed Co-Editor of the American Journal of Insanity, 1904, becoming the first Canadian to hold the position. He was appointed Royal Commissioner to investigate and report on conditions at the Provincial Asylum for the Insane at New Westminster, British Columbia, and then Royal Commissioner investigating methods of treatment of the insane in Europe, 1907. Further, Clarke was Vice-President of the Canadian Hospital Association from 1907-1908.

Prompted by his despair at witnessing the severe overcrowding at mental institutions, Clarke, beginning around 1895, began to keenly focus on the disproportionate rate of admissions amongst immigrant populations. Thus began one of the two obsessions that seemed to dominate the last three decades of Clarke’s professional life, alongside his ongoing perception of political interference in hospital affairs. In 1905 he lobbied for more and better-trained psychiatrists as medical inspectors of potential immigrants. In addition, he began publishing articles on the ‘defective and insane’ immigrant. This produced an ‘unpleasant controversy’ amongst some politicians and resulted in the (brief) taming of Clarke’s campaign. But by 1907 Clarke’s attitude towards immigrants was hardening. In his annual report, the word ‘evil’ had crept into the text, and the term ‘medical inspection’ had been replaced with the words ‘getting rid of them’.

In December of 1909 Clarke persuaded the Board of Trustees of Toronto General Hospital to establish an outpatient service, Canada’s first psychiatric clinic. It was called the ‘Ward Clinic’ and Dr. Ernest Jones (later Freud’s biographer) was its first Medical Director. The clinic was modeled after one in Munich operated by pioneering German psychiatrist, Emil Kraepelin, originator of an early scientific classification of mental diseases. The Toronto clinic closed for a year upon Jones’s return to England, but was reopened in 1914 for the study of “feeble-mindedness” with Dr. Clarke as Director. Clarke’s daughter, Miss Emma deVeber Clarke, was the Social Service Nurse. C.K. Clarke also had the responsibility, in 1915, for organizing the University’s No. 4 Overseas Hospital, consisting of 1,040 beds, and supervising a clinic for venereal diseases. In 1918, he became consultant in psychiatry to Military District No.2 (Toronto and Central Ontario). The year 1918 also saw Clarke, Dr. Clarence M. Hincks, and Dr. Helen MacMurchy (and others) found the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene (CNCMH).

From its inception until the time of his death, Clarke was Medical Director of the CNCMH, later (1950) re-named the Canadian Mental Health Association. One of the main objectives of the Committee was mental examination of immigrants, including children, to ensure a ‘better’ selection of newcomers. This prompted a major research project on Canadian immigration. Additionally, mental hygiene surveys were undertaken at the requests of the provinces of Manitoba in 1918, British Columbia in 1919, and Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia in 1920. Dr. Clarke, alongside Dr. Hincks, was one of the principal investigators. Dr. Clarke wondered why a country as young as Canada should have to bear such a heavy burden of mental illness and mental deficiency. He believed that this was due to the malign consequences of importing insane and defective immigrants into Canada and a significant rate of export of the “better class” of Canadians to the United States. Clarke saw this as a serious menace to Canada’s nationhood. Clarke thus persuaded the government to introduce a restrictive immigration policy that led to the amending of the Immigration Act of 1919 and extended the list of prohibited persons to include mental defectives, the mentally ill, psychopaths, and alcoholics as well as those who had committed crimes involving ‘moral turpitude’. In the year following the new Act, Clarke spent a month in St. Johns personally supervising the landing of some four thousand immigrants and advising and instructing the Inspectors on how to examine them. From his Toronto clinic he drew statistical findings about immigrants that are now seen as dubious and unrepresentative, but which were then readily received in many quarters. On May 24, 1923 Dr. Clarke was invited by the Royal Medico-Psychological Association of Great Britain to deliver the fourth annual prestigious Maudsley Lecture. He devoted a major part of his address to the ‘crisis’ caused by the migration into Canada of large numbers of mentally ill and intellectually subnormal adults and children, many of them British.

At crucial stages during the 1920s Clarke’s two chief acolytes, Farrar and Hincks, encouraged the introduction of the eugenics legislation that was enacted in Alberta and British Columbia. Clarke had been urging his medical colleagues and successive governments, for the better part of 25 years, to support the establishment of a psychiatric institute in Toronto; this, one of his most cherished ambitions, was realized a few months before he died. On October 12, 1923, he took part in laying the cornerstone for the Toronto Psychiatric Hospital. Clarke also arranged for one of his protégés, Dr. C.B. Farrar, to become its first director and his direct successor as the University’s Professor (and Chair) of Psychiatry. During the 1920s two of Clarke’s children were also active in the field: Emma DeVeber Clarke was supervisor of mental hygiene nursing for the city while Dr. Eric Kent Clarke worked briefly as a psychiatrist in Toronto’s health department before emigrating to the United States; their physician brother, Harold, had emigrated previously. C.K. Clarke died of cardiovascular disease in 1924 and is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto. In addition to his many passionate professional pursuits and publications, Clarke wrote prose, limericks and ornithological observations. He also played violin and cello and, in later years, he was one of the three non-professional players in the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. Despite having lost two fingers in a hunting accident, he built boats, a house and a pipe organ. In 1890, with Dr. William Gage as a partner, he won the Canadian Doubles Tennis Championship. Clarke was commemorated as the namesake of the Toronto Psychiatric Hospital’s successor institution, the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, when it opened in 1966. The Clarke Institute merged with three other specialized mental health and addiction institutions in 1998, becoming the College Street Site of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Selective

C.K. Clarke was educated at Elora High School and Toronto University (M.B., 1878; M.D., 1879). He received an honourary LL.D. from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario in 1906. He was Clinical Assistant to Dr. Workman at the Toronto Hospital for the Insane, 1874-1878, and Assistant Physician of the same institution from 1878-1880. He was Assistant Superintendent at the Hamilton Hospital for the Insane, 1880-1881, Assistant Superintendent at Rockwood Hospital for the Insane, Kingston, 1881-1885, under Dr. Metcalf, Superintendent, Rockwood Hospital, Kingston, 1885-1905, Superintendent, Toronto Hospital for the Insane, 1905-1911 (replacing Dr. Daniel Clark), Medical Superintendent, Toronto General Hospital, 1911-1917 and Medical Director, Toronto General Hospital from1917-1918. Clarke first became a member of the University of Toronto’s teaching staff in 1889, while still the Superintendent of Rockwood.

He was also Professor of Mental Diseases at Queen’s University until coming to Toronto. In 1906, Clarke became the first Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto. He later served as Dean of the Medical Faculty at the University of Toronto from 1908-1920.

On March 15, 1887, in connection with the Hospital for Insane, Kingston, the medical staff gave the first of a series of lectures to the student nurses. This was the earliest attempt in Canada to provide formal psychiatric training for nurses caring for the mentally ill. The first class graduated in 1889. One of the students, Miss Theresa Gallagher, eventually became Head Nurse and Dr. Clarke’s second wife. Also at Rockwood, Clarke introduced an infirmary for acute cases, occupational therapy, established non-restraint and had convalescent homes and outdoor treatment of cases of tuberculosis put into existence. He steadfastly tried to destroy any resemblance between an asylum and a prison, and would eventually succeed in reducing the stigmatic designation by having Ontario’s asylums renamed ‘hospitals for the insane’. Clarke was appointed Co-Editor of the American Journal of Insanity, 1904, becoming the first Canadian to hold the position. He was appointed Royal Commissioner to investigate and report on conditions at the Provincial Asylum for the Insane at New Westminster, British Columbia, and then Royal Commissioner investigating methods of treatment of the insane in Europe, 1907. Further, Clarke was Vice-President of the Canadian Hospital Association from 1907-1908.

Prompted by his despair at witnessing the severe overcrowding at mental institutions, Clarke, beginning around 1895, began to keenly focus on the disproportionate rate of admissions amongst immigrant populations. Thus began one of the two obsessions that seemed to dominate the last three decades of Clarke’s professional life, alongside his ongoing perception of political interference in hospital affairs. In 1905 he lobbied for more and better-trained psychiatrists as medical inspectors of potential immigrants. In addition, he began publishing articles on the ‘defective and insane’ immigrant. This produced an ‘unpleasant controversy’ amongst some politicians and resulted in the (brief) taming of Clarke’s campaign. But by 1907 Clarke’s attitude towards immigrants was hardening. In his annual report, the word ‘evil’ had crept into the text, and the term ‘medical inspection’ had been replaced with the words ‘getting rid of them’.

In December of 1909 Clarke persuaded the Board of Trustees of Toronto General Hospital to establish an outpatient service, Canada’s first psychiatric clinic. It was called the ‘Ward Clinic’ and Dr. Ernest Jones (later Freud’s biographer) was its first Medical Director. The clinic was modeled after one in Munich operated by pioneering German psychiatrist, Emil Kraepelin, originator of an early scientific classification of mental diseases. The Toronto clinic closed for a year upon Jones’s return to England, but was reopened in 1914 for the study of “feeble-mindedness” with Dr. Clarke as Director. Clarke’s daughter, Miss Emma deVeber Clarke, was the Social Service Nurse. C.K. Clarke also had the responsibility, in 1915, for organizing the University’s No. 4 Overseas Hospital, consisting of 1,040 beds, and supervising a clinic for venereal diseases. In 1918, he became consultant in psychiatry to Military District No.2 (Toronto and Central Ontario). The year 1918 also saw Clarke, Dr. Clarence M. Hincks, and Dr. Helen MacMurchy (and others) found the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene (CNCMH).

From its inception until the time of his death, Clarke was Medical Director of the CNCMH, later (1950) re-named the Canadian Mental Health Association. One of the main objectives of the Committee was mental examination of immigrants, including children, to ensure a ‘better’ selection of newcomers. This prompted a major research project on Canadian immigration. Additionally, mental hygiene surveys were undertaken at the requests of the provinces of Manitoba in 1918, British Columbia in 1919, and Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia in 1920. Dr. Clarke, alongside Dr. Hincks, was one of the principal investigators. Dr. Clarke wondered why a country as young as Canada should have to bear such a heavy burden of mental illness and mental deficiency. He believed that this was due to the malign consequences of importing insane and defective immigrants into Canada and a significant rate of export of the “better class” of Canadians to the United States. Clarke saw this as a serious menace to Canada’s nationhood. Clarke thus persuaded the government to introduce a restrictive immigration policy that led to the amending of the Immigration Act of 1919 and extended the list of prohibited persons to include mental defectives, the mentally ill, psychopaths, and alcoholics as well as those who had committed crimes involving ‘moral turpitude’. In the year following the new Act, Clarke spent a month in St. Johns personally supervising the landing of some four thousand immigrants and advising and instructing the Inspectors on how to examine them. From his Toronto clinic he drew statistical findings about immigrants that are now seen as dubious and unrepresentative, but which were then readily received in many quarters. On May 24, 1923 Dr. Clarke was invited by the Royal Medico-Psychological Association of Great Britain to deliver the fourth annual prestigious Maudsley Lecture. He devoted a major part of his address to the ‘crisis’ caused by the migration into Canada of large numbers of mentally ill and intellectually subnormal adults and children, many of them British.

At crucial stages during the 1920s Clarke’s two chief acolytes, Farrar and Hincks, encouraged the introduction of the eugenics legislation that was enacted in Alberta and British Columbia. Clarke had been urging his medical colleagues and successive governments, for the better part of 25 years, to support the establishment of a psychiatric institute in Toronto; this, one of his most cherished ambitions, was realized a few months before he died. On October 12, 1923, he took part in laying the cornerstone for the Toronto Psychiatric Hospital. Clarke also arranged for one of his protégés, Dr. C.B. Farrar, to become its first director and his direct successor as the University’s Professor (and Chair) of Psychiatry. During the 1920s two of Clarke’s children were also active in the field: Emma DeVeber Clarke was supervisor of mental hygiene nursing for the city while Dr. Eric Kent Clarke worked briefly as a psychiatrist in Toronto’s health department before emigrating to the United States; their physician brother, Harold, had emigrated previously. C.K. Clarke died of cardiovascular disease in 1924 and is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto. In addition to his many passionate professional pursuits and publications, Clarke wrote prose, limericks and ornithological observations. He also played violin and cello and, in later years, he was one of the three non-professional players in the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. Despite having lost two fingers in a hunting accident, he built boats, a house and a pipe organ. In 1890, with Dr. William Gage as a partner, he won the Canadian Doubles Tennis Championship. Clarke was commemorated as the namesake of the Toronto Psychiatric Hospital’s successor institution, the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, when it opened in 1966. The Clarke Institute merged with three other specialized mental health and addiction institutions in 1998, becoming the College Street Site of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Selective

Bibliography:

bibliography: Charles Kirk Clarke: A Pioneer of Canadian Psychiatry by Cyril Greenland. University of Toronto Press for the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, 1966. Dictionary of Canadian Biography, entry for C.K. Clarke by Ian R. Dowbiggin. forthcoming. Keeping America Sane: Psychiatry and Eugenics in the United States and Canada, 1880-1940 by Ian R. Dowbiggin. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1997. “’Keeping This Young Country Sane’: C.K.Clarke, Immigration Restriction, and Canadian Psychiatry, 1890-1925”, by Ian R. Dowbiggin. The Canadian Historical Review, 76:4, December 1995. Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada, 1885-1945, by Angus McLaren. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1998. Who’s Who in Canada, International Press Ltd., 1922.