From the Minden Home Child Event of May 2012

Author Kenneth Bagnell summarizes his address given that day.

By Kenneth Bagnell

|

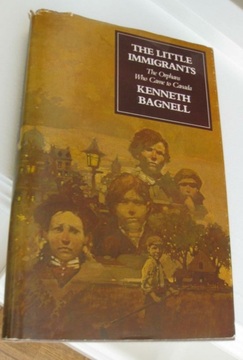

Kenneth Bagnell’s book The Little Immigrants is available on Amazon.com or by ordering through most booksellers. His second book Canadese: A Portrait of the Italian Canadians, also published by Macmillan, is also available through Amazon.com. For his other writings: www.kennethbagnell.com

|

I’m still surprised that a book of mine, one I wrote roughly thirty-five years ago, The Little Immigrants, is still available after over a dozen printings. I was fortunate. In part the book – the story of neglected British children shipped to Canadian farm families mostly between the 1870s and 1930s -- caught the attention of the media when it first appeared in 1980. That along with favorable reviews helped place it on all the country’s bestseller lists for about a year. But the fact that it’s still in print is due to something else: the ever growing interest in genealogy, especially among descendants of what we’ve come to call “the home children.” Mainly, this admirable interest is due to two things: first, the descendants want to know more fully what their parents, grandparents, or great grandparents went through. Secondly they want to assure the so-called “home children” their deserved and permanent place in Canadian history.

Most of the children – estimates of how many were shipped range from about 70,000 to 100,000 – were settled in Ontario, in theory to be welcomed into families who would treat them almost as their own. Naturally, as with so much of our thinking – especially regarding children – this was highly idealized. Most of the children were used as cheap labor, in the fields or, in the case of girls, in the kitchen. “We were,” said the legendary J. S. Woodsworth, a founder of the CCF party, “bringing children into Canada in the guise of philanthropy and turning them into cheap labor.” (He said this in the 1920s.) |

In early spring, 2012, I was invited to speak to a gathering of men and women, most having a parent or grandparent who was a home child. The meeting -- at which various people spoke, some descendants, others writers, historians or genealogists -- was held on Saturday, May 26, 2012, in the community cultural centre of Minden, Ontario. (This was helpful to me since my wife Barbara and I were spending a week or so at our cottage not far from Minden.) Once I was invited and able to attend, I gave some thought to what, so many years after the book came out, I might say. In a sense the lapse of time had its advantage: it gave the writer a mature perspective, also allowing him to include the developments of intervening years.

I decided what I’d speak on: the questions I was most often asked by journalists – television, radio and newspaper people -- during the national book tour arranged by my first publisher of The Little Immigrants, Macmillan of Canada. I began the talk by explaining my view that once you’ve been interviewed on your book five or six times you more or less know the basic questions that will be asked for the rest of the tour. Moreover, as a journalist who has also been a television interviewer, it’s my view that those questions are ones the public would like answered. After all, journalists try to ask questions they feel are on the public’s mind. So I mention here five questions I believe were on the minds of readers when the book first came out back in 1980.

1. The opening question was often this: “Are you a descendant of a home child?” No I’m not. I knew vaguely about child emigration when I was a child in Nova Scotia after a day, probably in the late 1940s, when my mother, explaining the background of a young woman, said to me: “Annie came from away when she was a little girl.” My curiosity about what lay behind the explanation stayed with me for years until in the early 1970s I did some preliminary research. Quite soon, I then felt strongly drawn to the subject as a writer. To write the book was a creative decision, not unlike the decision of an artist drawn to a scene, a playwright drawn to a plot. I decided to write it, in large part, in novelistic form, but with all the facts as accurate as possible. Some things happened that were strikes of good fortune. For example a friend suggested I have a letter carried in Canada’s Community Newspapers, many of them rural, inviting former “home children” willing to share their stories, to contact me. A large number, maybe a hundred, maybe more, from almost every province did. They were anxious to talk. I set out to cross the country, recording as many as possible over a period of two years. I also contacted Barnardo’s in London, England, to which Barbara I travelled for research, and found the staff most co-operative for which I’m deeply indebted.

2. A question often asked near the beginning of many interviews was this:

“What led to children, many so young, being sent to Canada this way?” Scholars of immigration refer to what they call a “push-pull” factor in much, if not all, migration. In England, mostly before and during the 1860s, a sense developed that the major industrial cities – London, Birmingham, Manchester and some others – were overwhelmed by large populations and hard times. So “the push” was on to reduce the population. There had long been public complaints, often by civic leaders, typified by this comment back in the 1820s by a magistrate: “I conceive that London has got too full of children.” (He recommended migration as one answer.) Before long homes were being set up to take such children in. Among the first to open an institution was social worker Annie MacPherson and her two sisters. She also put in words the so-called “pull-factor” from Canada. “We who labour here,” she wrote, “are tired of relieving misery from hand to mouth, and also heartsick of seeing hundreds of families pining away for want of work, when over on the shores of Ontario, the cry is heard, ‘come over and we will help you.’” It was then a small step to the broad conclusion as one of the later and major figures in child emigration put it: “An open door at the front requires and open door at the back’ That back door was to lead mostly to Canada.

3. In virtually all the interviews I did, this question was asked near the beginning: “Isn’t it true that the children were probably better off in Canada than they would be if they’d stayed in the miserable conditions facing them in England?” I have a problem, I replied, with the question. It suggests the children had but two options -- the abject poverty of their situation in England or emigration to remote farms in Canada. But there’s a third possibility: that England might have dealt with its own social problems rather than exporting them to Canada. In fact, a British Commission actually came to Canada in 1924, and after touring much of the country visiting farms and home children who lived on them, returned to England and recommended a change in policy: that only children of mid to late teens (school leaving age) be permitted to emigrate in the scheme. But even before the commission arrived, the greatly respected J.S. Woodsworth, founding leader of the CCF (today’s NDP) put his finger on the truth: “We were bringing children into Canada in the guise of philanthropy and turning them into cheap labour.”

4. “Surely,” I was often asked, “some children were placed with caring families? I said that was true – now and then. In Montreal a married couple actually requested a very young child who would become their adopted daughter. The parents were affluent, part of the cultural elite of their city. The child became an achiever, encouraged by her parents so that she became, one of the early female leading graduates of McGill. It would be an error to assume this was common. I heard more often of home children, male and female, who were never sure they were truly welcomed or truly belonged. Take as an example, the experience told me by a woman in southern Ontario who had been settled with a farm family not far from Belleville where I interviewed her in the late 1970s.

A few weeks after she’d arrived and been placed she heard that the family’s only daughter was to be married in a few months. “How I looked forward to that wedding,” she told me, “it was to be such a happy event everybody in the household anticipated it, and so I did as well. So I was so happy.” But a day or so before the wedding, she was told, in clear terms, she was not to show her face outside the kitchen. To some, this obviously seems a trivial matter. Not to a small child who felt she was to be part of the family she was sent to. She was an example of what James S. Woodsworth said: she was a child worker, sent to Canada under the guise of philanthropy.

5. Were there, I was also asked, any truly successful stories? Yes, I said, depending on how broadly we define success. Here and there were home children who became Christian ministers or prosperous farmers mostly because as years passed they inherited the farmland where they’d been placed, land which over the years had become quite valuable. One story was truly exceptional. I came upon it almost by accident near the end of my research in 1979.

A small boy was placed with a farm family not far from Lindsay, Ontario. The couple didn’t know what to make of him: he asked if he might take a bath, which led them to tell him he was too demanding for they themselves didn’t ever have a bath. He sat at the table most evenings writing poetry. To relieve his boredom he went to Sunday service at a nearby Presbyterian Church. The minister sensed how attentive he was during the sermon. He and his wife soon began inviting the boy to the manse for Sunday dinners with their family. In time, partly at the minister’s urging, the boy moved, on his own, to Toronto and once there, joined a working boys club at the YMCA. Y workers saw his high intelligence. Before long he was given an IQ test. Psychologists reviewing the results were astonished: a boy who had gone perhaps as far as grade six or seven in England – and virtually run away to get to Canada as an escape his family life -- was extraordinarily intelligent. With the Y’s help he finished high school in Toronto in roughly two years and was soon sent to Chicago to pursue a doctorate in sociology. His name was John R. Seeley. He was to become, in time, along with one of his YMCA benefactors, Murray Ross, one of the major influences in the creation of Canada’s renowned educational institution, York University.

When The Little Immigrants appeared in 1980, Dr. Seeley, then an academic in California was kind enough to come to Toronto, at the invitation of CBC Television on which he appeared with me on the program Front Page Challenge. Obviously, scores of other questions have been asked over the years, some of which I can answer, some not. But I was pleased to be able to take part in the gathering in Minden on May 26th, 2012. As I said, when concluding my talk, those who organized the gathering, and others who hold similar ones, participate in a very important exercise: they help assure that young children who endured a basically well intentioned if often very painful experience, are assured their place in Canada’s national memory.

I decided what I’d speak on: the questions I was most often asked by journalists – television, radio and newspaper people -- during the national book tour arranged by my first publisher of The Little Immigrants, Macmillan of Canada. I began the talk by explaining my view that once you’ve been interviewed on your book five or six times you more or less know the basic questions that will be asked for the rest of the tour. Moreover, as a journalist who has also been a television interviewer, it’s my view that those questions are ones the public would like answered. After all, journalists try to ask questions they feel are on the public’s mind. So I mention here five questions I believe were on the minds of readers when the book first came out back in 1980.

1. The opening question was often this: “Are you a descendant of a home child?” No I’m not. I knew vaguely about child emigration when I was a child in Nova Scotia after a day, probably in the late 1940s, when my mother, explaining the background of a young woman, said to me: “Annie came from away when she was a little girl.” My curiosity about what lay behind the explanation stayed with me for years until in the early 1970s I did some preliminary research. Quite soon, I then felt strongly drawn to the subject as a writer. To write the book was a creative decision, not unlike the decision of an artist drawn to a scene, a playwright drawn to a plot. I decided to write it, in large part, in novelistic form, but with all the facts as accurate as possible. Some things happened that were strikes of good fortune. For example a friend suggested I have a letter carried in Canada’s Community Newspapers, many of them rural, inviting former “home children” willing to share their stories, to contact me. A large number, maybe a hundred, maybe more, from almost every province did. They were anxious to talk. I set out to cross the country, recording as many as possible over a period of two years. I also contacted Barnardo’s in London, England, to which Barbara I travelled for research, and found the staff most co-operative for which I’m deeply indebted.

2. A question often asked near the beginning of many interviews was this:

“What led to children, many so young, being sent to Canada this way?” Scholars of immigration refer to what they call a “push-pull” factor in much, if not all, migration. In England, mostly before and during the 1860s, a sense developed that the major industrial cities – London, Birmingham, Manchester and some others – were overwhelmed by large populations and hard times. So “the push” was on to reduce the population. There had long been public complaints, often by civic leaders, typified by this comment back in the 1820s by a magistrate: “I conceive that London has got too full of children.” (He recommended migration as one answer.) Before long homes were being set up to take such children in. Among the first to open an institution was social worker Annie MacPherson and her two sisters. She also put in words the so-called “pull-factor” from Canada. “We who labour here,” she wrote, “are tired of relieving misery from hand to mouth, and also heartsick of seeing hundreds of families pining away for want of work, when over on the shores of Ontario, the cry is heard, ‘come over and we will help you.’” It was then a small step to the broad conclusion as one of the later and major figures in child emigration put it: “An open door at the front requires and open door at the back’ That back door was to lead mostly to Canada.

3. In virtually all the interviews I did, this question was asked near the beginning: “Isn’t it true that the children were probably better off in Canada than they would be if they’d stayed in the miserable conditions facing them in England?” I have a problem, I replied, with the question. It suggests the children had but two options -- the abject poverty of their situation in England or emigration to remote farms in Canada. But there’s a third possibility: that England might have dealt with its own social problems rather than exporting them to Canada. In fact, a British Commission actually came to Canada in 1924, and after touring much of the country visiting farms and home children who lived on them, returned to England and recommended a change in policy: that only children of mid to late teens (school leaving age) be permitted to emigrate in the scheme. But even before the commission arrived, the greatly respected J.S. Woodsworth, founding leader of the CCF (today’s NDP) put his finger on the truth: “We were bringing children into Canada in the guise of philanthropy and turning them into cheap labour.”

4. “Surely,” I was often asked, “some children were placed with caring families? I said that was true – now and then. In Montreal a married couple actually requested a very young child who would become their adopted daughter. The parents were affluent, part of the cultural elite of their city. The child became an achiever, encouraged by her parents so that she became, one of the early female leading graduates of McGill. It would be an error to assume this was common. I heard more often of home children, male and female, who were never sure they were truly welcomed or truly belonged. Take as an example, the experience told me by a woman in southern Ontario who had been settled with a farm family not far from Belleville where I interviewed her in the late 1970s.

A few weeks after she’d arrived and been placed she heard that the family’s only daughter was to be married in a few months. “How I looked forward to that wedding,” she told me, “it was to be such a happy event everybody in the household anticipated it, and so I did as well. So I was so happy.” But a day or so before the wedding, she was told, in clear terms, she was not to show her face outside the kitchen. To some, this obviously seems a trivial matter. Not to a small child who felt she was to be part of the family she was sent to. She was an example of what James S. Woodsworth said: she was a child worker, sent to Canada under the guise of philanthropy.

5. Were there, I was also asked, any truly successful stories? Yes, I said, depending on how broadly we define success. Here and there were home children who became Christian ministers or prosperous farmers mostly because as years passed they inherited the farmland where they’d been placed, land which over the years had become quite valuable. One story was truly exceptional. I came upon it almost by accident near the end of my research in 1979.

A small boy was placed with a farm family not far from Lindsay, Ontario. The couple didn’t know what to make of him: he asked if he might take a bath, which led them to tell him he was too demanding for they themselves didn’t ever have a bath. He sat at the table most evenings writing poetry. To relieve his boredom he went to Sunday service at a nearby Presbyterian Church. The minister sensed how attentive he was during the sermon. He and his wife soon began inviting the boy to the manse for Sunday dinners with their family. In time, partly at the minister’s urging, the boy moved, on his own, to Toronto and once there, joined a working boys club at the YMCA. Y workers saw his high intelligence. Before long he was given an IQ test. Psychologists reviewing the results were astonished: a boy who had gone perhaps as far as grade six or seven in England – and virtually run away to get to Canada as an escape his family life -- was extraordinarily intelligent. With the Y’s help he finished high school in Toronto in roughly two years and was soon sent to Chicago to pursue a doctorate in sociology. His name was John R. Seeley. He was to become, in time, along with one of his YMCA benefactors, Murray Ross, one of the major influences in the creation of Canada’s renowned educational institution, York University.

When The Little Immigrants appeared in 1980, Dr. Seeley, then an academic in California was kind enough to come to Toronto, at the invitation of CBC Television on which he appeared with me on the program Front Page Challenge. Obviously, scores of other questions have been asked over the years, some of which I can answer, some not. But I was pleased to be able to take part in the gathering in Minden on May 26th, 2012. As I said, when concluding my talk, those who organized the gathering, and others who hold similar ones, participate in a very important exercise: they help assure that young children who endured a basically well intentioned if often very painful experience, are assured their place in Canada’s national memory.

British Home Children mentioned in Kenneth's book

William Andrews, Walter Axtell, Charles Beer, Lillian Bradley (Lillian Edwards, arrived in 1921 married Thomas E Bradley in 1928), Mabel Carlton, William Coe, Margaret Crooks (Margaret Ethel CHAPMAN married Joseph Crooks in 1929), Harold Dodham, John Dove, Eva Drain, Flora Durni, Charles Elliott, Winnifred Frost, Victor Fry, Charles Goddard, Roy Grant, George Gregory, William Harris, Ellen Higgins, Kathleen Hobday, Emily Leader, Norman Mckinlay, William Maclaren, Cant Major, Katherine Major, Nellie Merry, John Mileham, Phyllis Owen, Harry atience, James Payton, Arthur Pope, Annie Smith, Ann Louise Stuart, Richad Todd, Alice Tomison, Horace Weir, Cyril White, Ernest Wilerton, Lily Wilson, Margaret Wilson.

Tapes of the interviews done were placed in the Public Archives of Canada in Ottawa.

William Andrews, Walter Axtell, Charles Beer, Lillian Bradley (Lillian Edwards, arrived in 1921 married Thomas E Bradley in 1928), Mabel Carlton, William Coe, Margaret Crooks (Margaret Ethel CHAPMAN married Joseph Crooks in 1929), Harold Dodham, John Dove, Eva Drain, Flora Durni, Charles Elliott, Winnifred Frost, Victor Fry, Charles Goddard, Roy Grant, George Gregory, William Harris, Ellen Higgins, Kathleen Hobday, Emily Leader, Norman Mckinlay, William Maclaren, Cant Major, Katherine Major, Nellie Merry, John Mileham, Phyllis Owen, Harry atience, James Payton, Arthur Pope, Annie Smith, Ann Louise Stuart, Richad Todd, Alice Tomison, Horace Weir, Cyril White, Ernest Wilerton, Lily Wilson, Margaret Wilson.

Tapes of the interviews done were placed in the Public Archives of Canada in Ottawa.

Dedicated to all who experienced Child Immigration 1618-1967

Forgotten Children

by Walter Richard Williams

|

Can anybody hear me

I'm neither brave nor bold, I'm just a child from Birmingham I'm only 9 years old, We're standing on the cold deck Franconia is her name, they say it's high adventure but it doesn't feel the same, Mommy's taken poorly Daddy just can't work, Injured in the Great War fighting in the dirt, We're sailing off across the sea, a better life they say There's seven of us children, but Mommy and Daddy stay. Please don't forget us Mommy, please bring us back some day, Don't leave us in this wilderness, don't hurt us Lord we pray. We're going on holiday, across the ocean blue, but something just don't seem right, shouldn't Mommy and Daddy too, They say we'll all learn farming, Whatever that may mean, We'll love the pigs, hug the sheep, and keep the stable clean, They mention things like "young blood", to help the country grow, Beatrice 3, Louis 10, seven birthdays in a row, I lost them at the station, they said it's for the best, I don't like the look of this they're taking off my vest. Please don't forget us mommy Please bring us back some day, Don't leave us in this wilderness, Don't hurt us Lord we pray. |

I'm told I'm fit and healthy

they put me on a train, for what seemed like forever I traveled in the rain, A man was there to meet me, He didn't seem to care, That I was cold and hungry in the middle of nowhere, "work hard" he said, and then you'll eat, Co's that's the way things go So wipe them tears from your eyes You're Mommy and Daddy know, "I'll teach you how to farm" he yelled, then beat me with a stick, I've had not food for 3 long days Oh Mommy I feel so sick. Please don't forget us Mommy, Please bring us back some day, Don't leave us in this wilderness Don't hurt us Lord we pray. 60 years we've been here they never told us why, After 30 years I found the rest. I couldn't even cry, Some were lucky, some were not but one thing we all shared, Our families had forgotten us and no-one really cared. We can't go back to England, as no-one knows we're here, Maybe the day will come about Some family will appear. Then we can tell our story, Orphans we are not - Just forgotten children Of this lonely plot..... |

The first chapter in the book by Kenneth Bagnell, The Little Immigrants, tells the story of Horace Weir for whom this poem was written.

an online excerpt of this book can be seen at:

"The Little Immigrants"

an online excerpt of this book can be seen at:

"The Little Immigrants"