The Stewart children lost & found

written by and published with permission of Paul Barton of London, England

CORK

My Great Grandfather Johnny Stewart was born in Cork, Ireland in 1867, the son of a bookbinder called James Stewart and his wife Catherine. My mother would tell me of his playful nature that the other adults in the family regarded as somewhat infantile, but he was adored by the children. However, he carried a deep sadness that would bring him to tears. My mother’s recollection was that his family had sailed away to America, leaving him behind. In fact, my research has shown that they went to Canada, not America. In later life he would tearfully regret that he failed to maintain any sort of correspondence with his dispersed family and eventually lost touch. The departure of the Stewarts was family legend, and a few years ago, when I got my first computer, I began a quest to discover what really happened to them. I had no great expectations but, bit by bit I was able to trace the story and to unfold a tragedy that has left me astonished and deeply moved.

LONDON

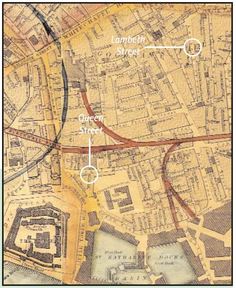

Johnny would in later years regale his family with tales of an idyllic childhood in rural Ireland, but research has shown this to be 'a touch of the Blarney’. In 1869 we find the family in London where Johnny was baptised for a second time aged 22 months. This took place at St Paul, Dock Street, Tower Hamlets, known as the Seamen's Chapel, on 10th October. The address given was 6 Queen Street, near the Tower of London at the south end of the Minories.

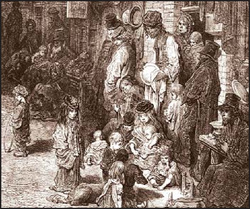

The Irish Potato Famine bequeathed an exodus of Irish immigrants to Whitechapel, joining the existing social melting pot along with Eastern Europeans and Jews. Whitechapel thus transformed itself into an area of urban housing based upon this influx of immigrants. Indeed, the almost complete lack of economic and social stability for the residents of Whitechapel was one of the reasons why Jack The Ripper was never caught; very few residents left any trace that they ever existed.The alleyways and houses in Whitechapel were cramped so close together that up to three families lived together in a two bedroom dwelling. Housing was in the control of individual local landlords,not the council, so eviction was a common feature of life in the area. As a result most residents lived on a day to day basis with employment prone to extreme fluctuations and mortality rates extremely high, especially in comparison to the richer West End of the city.

Sanitation was an issue only tackled byWestminster in the second half of the nineteenth century, but the problem in Whitechapel was overcrowding. Cholera outbreaks in Whitechapel in 1830 and 1866 underlined the marginalisation of the community from the rest of the city. Conditions in Whitechapel remained well below the standard of living for the remainder of the century, though increased state intervention had at least recognized the gravity of the problem. Bad conditions, poverty, drunkenness, prostitution, begging and thieving went together.

The Irish Potato Famine bequeathed an exodus of Irish immigrants to Whitechapel, joining the existing social melting pot along with Eastern Europeans and Jews. Whitechapel thus transformed itself into an area of urban housing based upon this influx of immigrants. Indeed, the almost complete lack of economic and social stability for the residents of Whitechapel was one of the reasons why Jack The Ripper was never caught; very few residents left any trace that they ever existed.The alleyways and houses in Whitechapel were cramped so close together that up to three families lived together in a two bedroom dwelling. Housing was in the control of individual local landlords,not the council, so eviction was a common feature of life in the area. As a result most residents lived on a day to day basis with employment prone to extreme fluctuations and mortality rates extremely high, especially in comparison to the richer West End of the city.

Sanitation was an issue only tackled byWestminster in the second half of the nineteenth century, but the problem in Whitechapel was overcrowding. Cholera outbreaks in Whitechapel in 1830 and 1866 underlined the marginalisation of the community from the rest of the city. Conditions in Whitechapel remained well below the standard of living for the remainder of the century, though increased state intervention had at least recognized the gravity of the problem. Bad conditions, poverty, drunkenness, prostitution, begging and thieving went together.

Baptised at the same time as Johnny was a younger brother called Thomas. He had been born 29th August 1868 - less than nine months after Johnny and presumably premature. By the time of the 1871 census Thomas had died. The family were then living at 6 Lambeth Street, St Mary Whitechapel, east of their previous home and now overbuilt by the modern offices of the Royal Bank of Scotland, whose frontage is in Whitechapel High Street. This was a fairly squalid part of the East End inhabited by expatriate Jews and Irish. James’s place of birth was given as Dublin, yet years later Johnny was to state that his father had been born in Edinburgh, either an error or more Blarney.

Living with James, Catherine and toddler Johnny was Catherine's widowed 50-year old mother Sarah Sheehan who was born in Cork. Catherine would have been heavily pregnant with her first daughter, Sarah. In 1872 she had James; a later census names another brother George of the same age, though he doesn't feature in any other records. Catherine, or Kate, was born in 1873 and then in 1876 another son, Alexander, baptised on Christmas Eve at Saint Jude, Commercial Road, Whitechapel which was to the north West of Lambeth Street. James Senior’s health at this time was beginning to decline.

Living with James, Catherine and toddler Johnny was Catherine's widowed 50-year old mother Sarah Sheehan who was born in Cork. Catherine would have been heavily pregnant with her first daughter, Sarah. In 1872 she had James; a later census names another brother George of the same age, though he doesn't feature in any other records. Catherine, or Kate, was born in 1873 and then in 1876 another son, Alexander, baptised on Christmas Eve at Saint Jude, Commercial Road, Whitechapel which was to the north West of Lambeth Street. James Senior’s health at this time was beginning to decline.

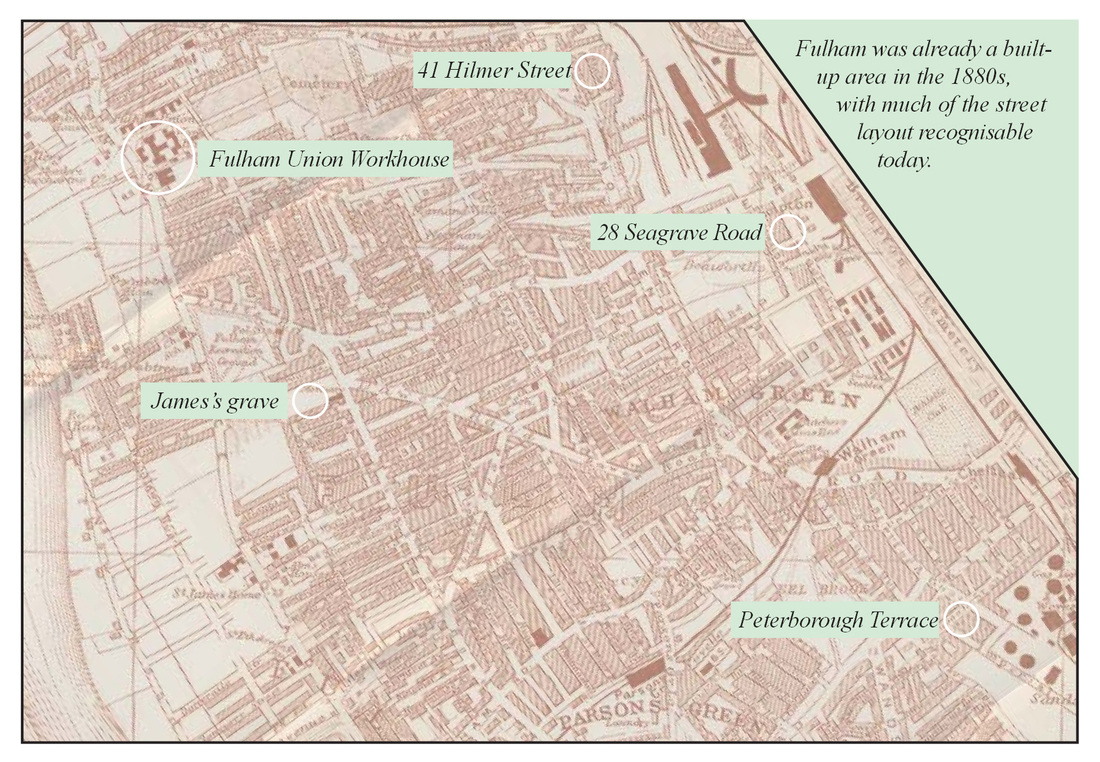

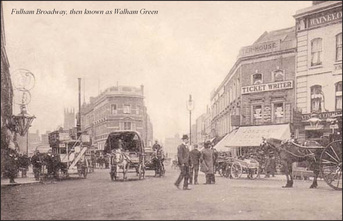

FULHAM

By the end of the decade the family had settled in Fulham, West London. Fulham had been a largely rural area until the arrival of the railways. As a result, the second half of the nineteenth century saw a huge increase in population, from 10,000 in 1801 to 250,000 in 1901. By the time of little Charley's birth in 1879 the family were living at 27 Seagrave Road, Fulham. A terrace of tall three-storey houses, it was at the northern end near the junction with Lillie Road, facing a pub which still stands called the Atlas. Their end of the street was a mixture of classes, with the social scale improving further down at the southern end. At that southern end was the Western Smallpox Hospital - called the Wolston Hospital so as not to give the district a bad name. Also at that end was the London Road Car company’s stables, bus factory and repair shop, covering much ground.

James Stewart had been diagnosed with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in 1877, an infectious disease of the lungs. TB is caught by breathing in droplets containing the bacteria, for example, when an infected person coughs or sneezes. In many people who become infected, the immune system successfully fights off the infection. Anyone can get TB, but it’s more likely if you already have another disease, don’t eat well, or live in overcrowded or sub-standard housing. This may have been the reason the family moved out of Whitechapel. TB is characterized by several symptoms; a persistent cough accompanied by large amounts of phlegm, sometimes bloodstained; swollen glands, especially in the neck; tiredness; loss of appetite; weight loss; sweating at night; chest pain on breathing-in caused by inflammationof the membranes lining the lungs (pleurisy). The initial TB infection normally affects the lungs but often spreads to lymph nodes. It can also affect bones, joints and kidneys, and cause a type of meningitis (inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord).

By May 1880 his condition now included Laryngeal Tuberculosis, an uncommon and highly virulent, infectious form of the disease infecting the larynx, or the vocal chord area. His additional symptoms would now have included: hoarseness; pain on swallowing foods or fluids; pain in the ear; the constant sensation of something in the throat; a harsh, high pitched sound to his inward breathing; frothy, alkaline bloodstained sputum and a swollen throat. Tuberculosis caused the most widespread public concern in the 19th and early 20th centuries as the endemic disease of the urban poor. After the establishment in the 1880s that the disease was contagious,TB was made a notifiable disease in Britain; there were campaigns to stop spitting in public places, and the infected poor were ‘encouraged’ to enter sanatoria that rather resembled prisons.

James's plight would have been an extremely distressing experience for his family. He would have been struggling for breath, rasping, perhaps unable to speak. With swallowing becoming increasingly difficult even eating would have been an ordeal. His emaciated body must have been a painful reminder for Catherine of her childhood at the height of the Potato Famine.

On 1st June the three children Kate, Sarah and Jamie were admitted to Fulham Workhouse, who sent them onwards a couple of days later to become inmates at the West London District School in Ashford, Middlesex. This was clearly to spare them the distress of witnessing their father’s lingering but now inevitable death. Their final farewell to their waning father must have been touching in the extreme though the room would have been rank with the unfortunate man’s foul breath as a result of his condition. James died on 30th June. The witness was 49-year old Ellen Oakham, who also lived with her husband in the house. The burial took place at 3pm on Wednesday 6th July 1880 in a common grave in consecrated ground at Fulham cemetery. The following Sunday 10th July, the children were discharged from school and returned to Fulham workhouse where they remained for that day. The summer of 1880 was notedfor bad weather and rain, deepening the Stewart family’s misery.

On 15th October Johnny started his apprenticeship with bookbinder John Ramage, aged thirteen. Considering that the family breadwinner was now gone, Catherine would have dug deep into any savings she had to pay the £16 shillings required, roughly the equivalent of four months of James’s salary. It would be some time before Johnny would be earning enough to pay any of it back, but he would have been the only member of the family in a position to earn any sort of decent income. Three days later, on 18th October, young Kate and Jamie were sent back to the workhouse and on 18th November Kate was re-admitted to the Ashford school.

James Stewart had been diagnosed with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in 1877, an infectious disease of the lungs. TB is caught by breathing in droplets containing the bacteria, for example, when an infected person coughs or sneezes. In many people who become infected, the immune system successfully fights off the infection. Anyone can get TB, but it’s more likely if you already have another disease, don’t eat well, or live in overcrowded or sub-standard housing. This may have been the reason the family moved out of Whitechapel. TB is characterized by several symptoms; a persistent cough accompanied by large amounts of phlegm, sometimes bloodstained; swollen glands, especially in the neck; tiredness; loss of appetite; weight loss; sweating at night; chest pain on breathing-in caused by inflammationof the membranes lining the lungs (pleurisy). The initial TB infection normally affects the lungs but often spreads to lymph nodes. It can also affect bones, joints and kidneys, and cause a type of meningitis (inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord).

By May 1880 his condition now included Laryngeal Tuberculosis, an uncommon and highly virulent, infectious form of the disease infecting the larynx, or the vocal chord area. His additional symptoms would now have included: hoarseness; pain on swallowing foods or fluids; pain in the ear; the constant sensation of something in the throat; a harsh, high pitched sound to his inward breathing; frothy, alkaline bloodstained sputum and a swollen throat. Tuberculosis caused the most widespread public concern in the 19th and early 20th centuries as the endemic disease of the urban poor. After the establishment in the 1880s that the disease was contagious,TB was made a notifiable disease in Britain; there were campaigns to stop spitting in public places, and the infected poor were ‘encouraged’ to enter sanatoria that rather resembled prisons.

James's plight would have been an extremely distressing experience for his family. He would have been struggling for breath, rasping, perhaps unable to speak. With swallowing becoming increasingly difficult even eating would have been an ordeal. His emaciated body must have been a painful reminder for Catherine of her childhood at the height of the Potato Famine.

On 1st June the three children Kate, Sarah and Jamie were admitted to Fulham Workhouse, who sent them onwards a couple of days later to become inmates at the West London District School in Ashford, Middlesex. This was clearly to spare them the distress of witnessing their father’s lingering but now inevitable death. Their final farewell to their waning father must have been touching in the extreme though the room would have been rank with the unfortunate man’s foul breath as a result of his condition. James died on 30th June. The witness was 49-year old Ellen Oakham, who also lived with her husband in the house. The burial took place at 3pm on Wednesday 6th July 1880 in a common grave in consecrated ground at Fulham cemetery. The following Sunday 10th July, the children were discharged from school and returned to Fulham workhouse where they remained for that day. The summer of 1880 was notedfor bad weather and rain, deepening the Stewart family’s misery.

On 15th October Johnny started his apprenticeship with bookbinder John Ramage, aged thirteen. Considering that the family breadwinner was now gone, Catherine would have dug deep into any savings she had to pay the £16 shillings required, roughly the equivalent of four months of James’s salary. It would be some time before Johnny would be earning enough to pay any of it back, but he would have been the only member of the family in a position to earn any sort of decent income. Three days later, on 18th October, young Kate and Jamie were sent back to the workhouse and on 18th November Kate was re-admitted to the Ashford school.

By the time of the April 1881 census on 3rd April the rest of the family had relocated to 41 HilmerStreet, Fulham, now long since built over as a housing estate just north of the Earls Court Exhibition Centre, but at the time an ‘Irish ghetto’. Catherine, now 35, was a washer, and Johnny was already listed as a 14-year old bookbinder. Alexander was not on the census so it can be assumed that he had died. Apart from Kate who was at Ashford School, the rest of the family was there including Jamie, who should have been in the workhouse on that day – strangely he appears on the census sheet for the workhouse too. on the census who appeared to be Jamie’s twin. Apart from this I have found no other record of him and I wonder if this was some sort of error. Johnny would talk of witnessing the death of a brother, and seeing his soul rise to heaven. This could have been Alexander or maybe this mysterious George. On 22nd September 1881 little Jamie was transferred from the workhouse to the Ashford school. On 8th November, Catherine with 2-year old Charley and 10-year old Sarah were taken into the workhouse. On 1st December Sarah was re-admitted to Ashford School.

After James’s death the family became more and more institutionalised. Their fate largely lay in the hands of the Board of Guardians responsible for the Fulham workhouse and for the West London District School.It is worth reflecting that Victorian society was obliged to deal with an avalanche of destitutionon a scale unimaginable in the 21st century. Our view of 19th century poverty has to some extent been moulded by the writings of Charles Dickens, Lewis Carrol and others who were addressing their concerns not to us but to the people of their own time. The robust measures taken were a response to what would now be viewed as a national crisis. Consider for a moment how even a modern welfare state could cope with poverty and life-threatening disease on the scale faced by our forefathers.

After James’s death the family became more and more institutionalised. Their fate largely lay in the hands of the Board of Guardians responsible for the Fulham workhouse and for the West London District School.It is worth reflecting that Victorian society was obliged to deal with an avalanche of destitutionon a scale unimaginable in the 21st century. Our view of 19th century poverty has to some extent been moulded by the writings of Charles Dickens, Lewis Carrol and others who were addressing their concerns not to us but to the people of their own time. The robust measures taken were a response to what would now be viewed as a national crisis. Consider for a moment how even a modern welfare state could cope with poverty and life-threatening disease on the scale faced by our forefathers.

FULHAM WORKHOUSE

The workhouse was an old institution set up by a local parish to care for the poor. After the British Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, many of the communities with workhouses found they could no longer afford the support costs, so they came together to build and administer a single large workhouse - or union - for the care of their indigent poor, supported by the group of communities involved. After 1872, each workhouse or workhouse union was obliged by law to provide an education for its child residents until they reached 14 years. Fulham Union was one of these.

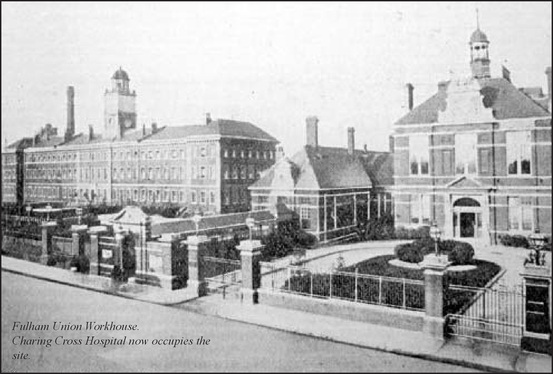

As far as can be established, Catherine spent just over four months in the Fulham Workhouse. This 35- year old building on east side of Fulham Palace Road was designed by Alfred Gilbert and adopted a corridor-plan layout with entrance block, T-shaped main block and infirmary running in parallel.

A newspaper report from when it was opened said:

The site was a plot of ground, five acres in extent, on the side of the high road leading from Hammersmith Church to Fulham, to contain 450 inmates. The style of the building is Italian, of red and window dressings. The plan includes spacious yards for each class of inmates, and playgrounds for boys and girls; besides a chapel. The main building, which is 150 feet from the road, is approached through an archway, over which is the Board Room; and on either side is accommodation for relieving officers, porters, &c.

The site later became Fulham Hospital and is now the Charing Cross Hospital. All the former workhouse buildings have been demolished. Life inside the workhouse was intended to be as off putting as possible. Men, women, children, the infirm,and the able-bodied were housed separately and given very basic and monotonous food such as watery porridge called gruel, or bread and cheese. All inmates had to wear the rough workhouse uniform and sleep in communal dormitories. Supervised baths were given once a week. The able-bodied were given hard work such as stone-breaking or picking apart old ropes called oakum. The elderly and infirm sat around in the day-rooms or sick-wards with little opportunity for visitors. Parents were only allowed limited contact with their children... perhaps for an hour or so a week on Sunday afternoon. The workhouse was not, however, a prison. People could, in principle, leave whenever they wished, for example when work became available locally. Some people, known as the ‘ins and outs’, entered and left quite frequently, treating the workhouse almost like a guest-house, albeit one with the most basic of facilities. For some, however, their stay in the workhouse would be for the rest of their lives.

People ended up in the workhouse for a variety of reasons. Usually, it was because they were too poor, or ill to support themselves. This may have resulted from such things as a lack of work during periods of high unemployment, or someone having no family willing or able to provide care for them when they became elderly or sick. Prior to the establishment of public mental asylums in the mid-nineteenth century (and in some cases even after that), the mentally ill and mentally handicapped poor were often consigned to the workhouse. Workhouses, though, were never prisons, and entry into them was generally a voluntary although often painful decision. It also carried with it a change in legal status. Until 1918, receipt of poor relief meant a loss of the right to vote.

Admission into the workhouse first required an interview to establish the applicant’s circumstances. This was most often undertaken by a Relieving Officer who would visit each part of the Union on a regular basis. However, the workhouse Master could also interview anyone in urgent need of admission. Formal admission into the workhouse proper was authorised by the Board of Guardians at their weekly meetings. In between times, new arrivals would be placed in a receiving or probationary ward. There the workhouse medical officer would examine them to check on their state of health. Those suffering from an illness would be placed in a sick ward. Upon entering the workhouse, paupers were stripped, bathed (under supervision), and issued with a workhouse uniform. Their own clothes would be washed and disinfected and then put into store along with any other possessions they had and only returned to them when they left the workhouse. Uniforms were usually made from fairly coarse materials with the emphasis being on hard-wearing rather than on comfort and fit. The uniform for able-bodied women was generally a shapeless, waistless dress reaching their ankles, with a pattern of broad, verticalstripes in a rather washed out blue on an off-white background. A smock was worn over it. Beneath such exterior garments, the women wore under-draws, a shift and long stockings, with a poke bonnet on their heads.

Inmates were strictly segregated into seven classes: • Aged or infirm men • Able bodied men, and youths above 13 • Youths and boys above 7 and under 13• Aged or infirm women • Able-bodied women and girls above 16• Girls above 7 and under 16• Children under 7

Each class had its own area of the workhouse. Husbands, wives and children were separated as soon as they entered the workhouse and could be punished if they even tried to speak to one another. Children under seven could be placed (if the Guardians thought fit) in the female wards and, from 1842, their mothers could have access to them ‘at all reasonable times’. Parents could also have an ‘interview’ with their children at some time in each day. The workhouse was like a small self-contained village. Apart from the basic rooms such as the dining- hall and dormitories, workhouses often had their own bakery, laundry, tailor and shoe-maker, vegetable gardens and orchards, and even a piggery. There would also be school-rooms, nurseries, fever-wards for the sick, a chapel, and a dead-room or mortuary. Once inside the workhouse, an inmate’s only possessions were their uniform and the bed they had in the large dormitory. Beds were simply constructed with a wooden or iron-frame, and could be as little as two feet across.

As far as can be established, Catherine spent just over four months in the Fulham Workhouse. This 35- year old building on east side of Fulham Palace Road was designed by Alfred Gilbert and adopted a corridor-plan layout with entrance block, T-shaped main block and infirmary running in parallel.

A newspaper report from when it was opened said:

The site was a plot of ground, five acres in extent, on the side of the high road leading from Hammersmith Church to Fulham, to contain 450 inmates. The style of the building is Italian, of red and window dressings. The plan includes spacious yards for each class of inmates, and playgrounds for boys and girls; besides a chapel. The main building, which is 150 feet from the road, is approached through an archway, over which is the Board Room; and on either side is accommodation for relieving officers, porters, &c.

The site later became Fulham Hospital and is now the Charing Cross Hospital. All the former workhouse buildings have been demolished. Life inside the workhouse was intended to be as off putting as possible. Men, women, children, the infirm,and the able-bodied were housed separately and given very basic and monotonous food such as watery porridge called gruel, or bread and cheese. All inmates had to wear the rough workhouse uniform and sleep in communal dormitories. Supervised baths were given once a week. The able-bodied were given hard work such as stone-breaking or picking apart old ropes called oakum. The elderly and infirm sat around in the day-rooms or sick-wards with little opportunity for visitors. Parents were only allowed limited contact with their children... perhaps for an hour or so a week on Sunday afternoon. The workhouse was not, however, a prison. People could, in principle, leave whenever they wished, for example when work became available locally. Some people, known as the ‘ins and outs’, entered and left quite frequently, treating the workhouse almost like a guest-house, albeit one with the most basic of facilities. For some, however, their stay in the workhouse would be for the rest of their lives.

People ended up in the workhouse for a variety of reasons. Usually, it was because they were too poor, or ill to support themselves. This may have resulted from such things as a lack of work during periods of high unemployment, or someone having no family willing or able to provide care for them when they became elderly or sick. Prior to the establishment of public mental asylums in the mid-nineteenth century (and in some cases even after that), the mentally ill and mentally handicapped poor were often consigned to the workhouse. Workhouses, though, were never prisons, and entry into them was generally a voluntary although often painful decision. It also carried with it a change in legal status. Until 1918, receipt of poor relief meant a loss of the right to vote.

Admission into the workhouse first required an interview to establish the applicant’s circumstances. This was most often undertaken by a Relieving Officer who would visit each part of the Union on a regular basis. However, the workhouse Master could also interview anyone in urgent need of admission. Formal admission into the workhouse proper was authorised by the Board of Guardians at their weekly meetings. In between times, new arrivals would be placed in a receiving or probationary ward. There the workhouse medical officer would examine them to check on their state of health. Those suffering from an illness would be placed in a sick ward. Upon entering the workhouse, paupers were stripped, bathed (under supervision), and issued with a workhouse uniform. Their own clothes would be washed and disinfected and then put into store along with any other possessions they had and only returned to them when they left the workhouse. Uniforms were usually made from fairly coarse materials with the emphasis being on hard-wearing rather than on comfort and fit. The uniform for able-bodied women was generally a shapeless, waistless dress reaching their ankles, with a pattern of broad, verticalstripes in a rather washed out blue on an off-white background. A smock was worn over it. Beneath such exterior garments, the women wore under-draws, a shift and long stockings, with a poke bonnet on their heads.

Inmates were strictly segregated into seven classes: • Aged or infirm men • Able bodied men, and youths above 13 • Youths and boys above 7 and under 13• Aged or infirm women • Able-bodied women and girls above 16• Girls above 7 and under 16• Children under 7

Each class had its own area of the workhouse. Husbands, wives and children were separated as soon as they entered the workhouse and could be punished if they even tried to speak to one another. Children under seven could be placed (if the Guardians thought fit) in the female wards and, from 1842, their mothers could have access to them ‘at all reasonable times’. Parents could also have an ‘interview’ with their children at some time in each day. The workhouse was like a small self-contained village. Apart from the basic rooms such as the dining- hall and dormitories, workhouses often had their own bakery, laundry, tailor and shoe-maker, vegetable gardens and orchards, and even a piggery. There would also be school-rooms, nurseries, fever-wards for the sick, a chapel, and a dead-room or mortuary. Once inside the workhouse, an inmate’s only possessions were their uniform and the bed they had in the large dormitory. Beds were simply constructed with a wooden or iron-frame, and could be as little as two feet across.

|

Workhouse rules included… • No written or printed paper of an impropertendency, or which may be likely to produce insubordination, shall be allowed to circulate, or be read aloud, among the inmates of the Workhouse. • No pauper shall play at cards, or at any game of chance, in the Workhouse; and the Master may take from any pauper, and keep until his departure from the Workhouse, any cards, dice, or other articles applicable to games of chance, which may be in his possession. • No pauper shall smoke in any room of the Workhouse, except by the special direction of the Medical Officer, or shall have any matches or other articles of a highly combustible nature in his possession, and the Master may take from any person any articles of such a nature. Breaking of workhouse rules fell into two categories: Disorderly Conduct, which could be punished by a withdrawal for food ‘luxuries’ such as cheese or tea, or the more serious Refractory Conduct, which could result in a period of solitary confinement. |

The inmates’ toilet facilities were often a simple privy... a cesspit with a simple cover with a hole on which to sit, shared perhaps by as many as 100 inmates. Dormitories were usually provided with chamber pots or earth closets... boxes containing dry soil which could afterwards be used as fertiliser. Once a week, the inmates were bathed (usually superintended; another assault on their dignity). The model timetable devised by the Poor Law Commissioners meant that the workhouse day began when the rising bell rang out at 6am from March to September and at 7am for the rest of the year. After prayers, breakfast followed from 6 to 7am. They then worked from 7 until noon. After an hour for lunch, work resumed until supper from 6 to 7pm. This was followed by more prayers and then bed, by 8pm at the latest.The main constituent of the workhouse diet was bread. At breakfast it was supplemented by gruel or porridge... both made from water and oatmeal (or occasionally a mixture of flour and oatmeal).Workhouse broth was usually the water used for boiling the dinner meat, perhaps with a fewonions or turnips added. Tea, often without milk, was provided for the aged and infirm at breakfast, together with a small amount of butter. Supper was usually similar to breakfast.

The mid-day dinner was the meal that varied most, although on several days a week this could just be bread and cheese. Other dinner fare included:

• pudding – either rice-pudding or steamed suet pudding. These would be served plain. In later years, suet-pudding might be served with gravy, or sultanas added to make plum pudding particularly when served to children or the infirm.

• meat and potatoes - the potatoes might be grown in the workhouse’sown garden; the meat was usually cheap cuts of beef or mutton, with occasional pork or bacon. Meat was usually boiled,although by the 1880s, some workhouses served roast meat.

• soup - this would usually be broth, with a few vegetablesadded and thickened with barley, rice or oatmeal. Although healthy in some respects, workhouse food wasoften created from the cheapest ingredients. Milk was oftendiluted with water and fruit was rarely included.

Meals were usually eaten in a large communal dining-hall which often doubled up as a chapel. Dining halls were equipped with scales so that inmates could get their food weighed if they thought it was below the regulation weight. However, practice did not always match theory and stories abounded about the quality and quantity of food in the workhouse diet. The ‘gruel cauldron’ was blamed for outbreaks of diarrhoea amongst inmates. Inmates were given varied work to perform, much of which was involved in running the workhouse. The women mostly did domestic jobs such as cleaning or helping in the kitchen or laundry. Some workhouseshad workshops for sewing, spinning and weaving or other local trades. Others had their own vegetable gardens where the inmates worked to provide food for the workhouse. No work, except necessary household work and cooking, was performed by inmates on Sunday, Good Friday, and Christmas Day.

Virtually all workhouses had at least a small infirmary block for the care of sick inmates, and the one in Fulham was well-equipped. However, with the exception of the medical officer, early nursing care in the workhouse was invariably in the hands of female inmates who would often not be able to read... a serious problem when dealing with labels on medicine bottles.

Relaxations very gradually began to creep in from the 1870s including the allowance of books, newspapers and snuff for the elderly, toys for the children, and tea-brewing facilities for deserving inmates. Living conditions were often healthier than existed in much poor housing of the time. Although monotonous, the food was regular and reasonably wholesome. The staff in many institutions were kindly, and the brutal treatment that was sensationalised in the press was probably much the exception.

|

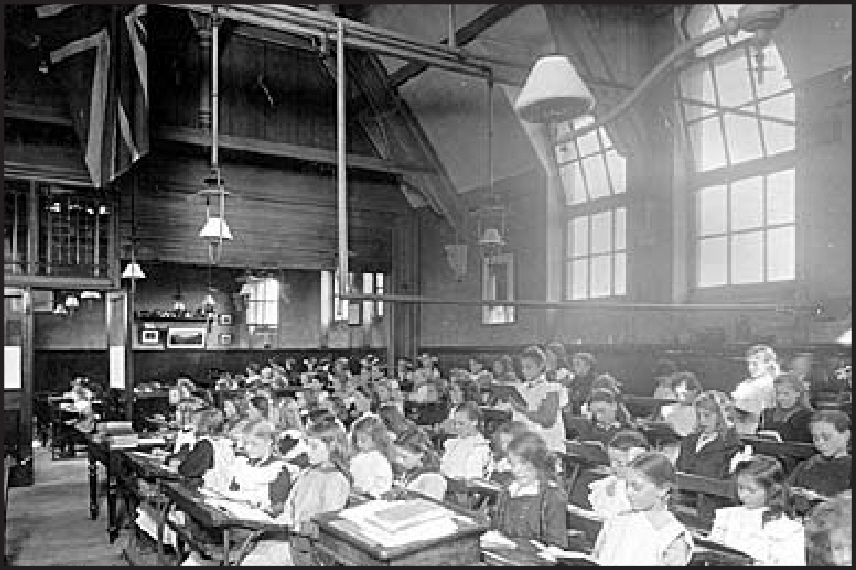

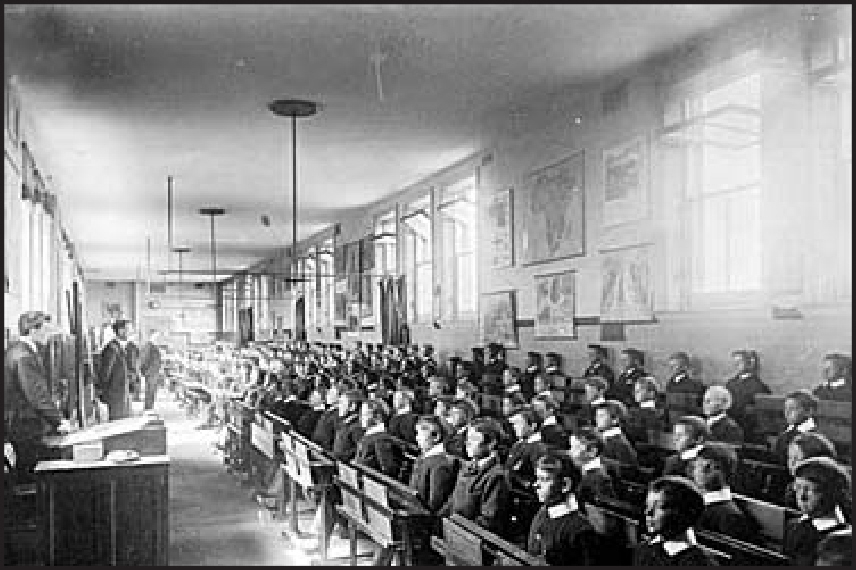

THE WEST LONDON DISTRICT SCHOOL, ASHFORD

The West London School District served theLondon Unions of Fulham, Hammersmith andPaddington. The School District Board built aschool for 800 children in 1869-72 at the westside of District Road, now Woodthorpe Road, at Ashford near Staines. The main building comprised a large central administrative block with long narrow wings to each side, one forboys and one for girls. A chapel was located atthe eastern end of the main building. A boiler-house, laundry and farm lay at the south of the school, and an infirmary to the south-west. Life for the inmates was quite harsh. They had to get up at 5.45am. After fires had been lit and the bathrooms cleaned they had breakfast at 7am. The children attended outside schools for their regular education. There was plenty of hard work and discipline. Many children were very unhappy but there seemed to be just as large a number who relished their time there, rather in the way that some recruits can take immediately to the army while others cannot tolerate the lifestyle. The youngsters slept in dormitories, ate and played in large communal areas and even enjoyed the luxury of an indoor swimming pool, with older pupils being taught practical subjects to set them up for when they left the care of the school. Many worked on the adjoining farm, which provided fresh produce for the school. In the grounds of the institution was a full sized replica of a sailing ship above the water line, used to train boys for the Merchant Navy |

On 23rd March 1882 Kate, Jamie and Sarah were discharged from Ashford School. Their mother and 3-year old Charley were discharged from the workhouse on 25th March. The next day, little Charley was baptised in the Anglican church of Saint John, Walham Green. The abode was given as Peterborough Terrace, south of Fulham Broadway. The Stewart's lives were about to change drastically.The older children were destined for a new life in the new world, courtesy of a philanthropist called Miss Maria Rye.

THE LOST CHILDREN

Most of the British poor who emigrated to Canada came in families, but an impressive number did not. Conspicuous in the latter’s ranks were thousands of young boys and girls who arrived unaccompanied by an adult family member. These children were apprenticed as agricultural labourers or, in the case of girls, sent to smaller towns or rural homes to work as domestic servants.

These were the ‘home children,’ slum youngsters plucked from philanthropic rescue homes and parish workhouse schools and dispatched to Canada and other British colonies to meet the soaring demand for cheap labour on Canadian farms and household labour in family homes. Many of these youngsters, of whom ranged in age between eight and ten, came from families of the urban poor who could not care for them properly. Other children, perhaps one-third their number, were orphans, while the balance were runaways or abandoned youngsters. At a time when few British emigrants were indentured in their overseas destinations, nearly all these child immigrants were apprenticed shortly after their arrival in Canada.

Although Canadian farms had received orphaned and destitute British children as early as the 1830s, it was not until 1868 that the home-children movement began in an organised way. In that year, Maria Susan Rye, the feminist daughter of a distinguished London solicitor, purchased an old jail on the outskirts of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, had it refurbished, and then made preparations to bring her first party of children to Canada. They arrived in October 1869 with the well-publicised blessings ofboth the Archbishop of Canterbury and The Times of London.

A few months later, Annie Macpherson, a Quaker working independently of Rye, brought another party of young children to Ontario. Soon, Louisa Birt of Liverpool (Macpherson’s sister), Thomas Barnardo of London, Leonard Shaw of Manchester, and William Quarrier of Glasgow… to name but a few of the best-known child-savers… were launching their own child-emigration programmes. Before long there was a proliferation of similar programmes, some of the more notable being implemented by the National Children’s Homes, Mr. Fegan’s Homes of Southwark and Westminster, the Middlemore Homesin Birmingham, the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society, and Miss Stirling of Edinburgh. Because Canada was closer to Britain than was Australia or New Zealand, it became the favoured destination for these charges.

Maria Rye eventually placed over 5,000 children, mostly girls, in many parts of Canada and the United States. Problems arose in 1875 when the Doyle Report was released. Mr. Doyle was sent in 1874 to inspect the children sent to Canada by the Unions (workhouses). His report was very negative about Miss Rye’s work, in particular about the lack of inspection after children had been placed, and she did not bring any children to Canada for a few years after the release of the report.

Underlying all these schemes was the activists’ belief that emigration was an effective way to rescue impoverished British children from the poorest and most crowded districts of Britain’s teeming cities. On Canadian farms, far from the temptations and polluted air of city life, their slum protégés would grow into healthy, industrious adults. Or so the thinking went. The long-lived programme eventually came to a halt in 1939, its end hastened not only by the Great Depression and the opposition of the Canadian labour movement but also by a change of thinking onthe part of Canadians and Britons. Both, it seems, could no longer tolerate the idea of philanthropic organisations separating young children from their parents and sending them to work in distant lands, no matter how salubrious the setting.

These were the ‘home children,’ slum youngsters plucked from philanthropic rescue homes and parish workhouse schools and dispatched to Canada and other British colonies to meet the soaring demand for cheap labour on Canadian farms and household labour in family homes. Many of these youngsters, of whom ranged in age between eight and ten, came from families of the urban poor who could not care for them properly. Other children, perhaps one-third their number, were orphans, while the balance were runaways or abandoned youngsters. At a time when few British emigrants were indentured in their overseas destinations, nearly all these child immigrants were apprenticed shortly after their arrival in Canada.

Although Canadian farms had received orphaned and destitute British children as early as the 1830s, it was not until 1868 that the home-children movement began in an organised way. In that year, Maria Susan Rye, the feminist daughter of a distinguished London solicitor, purchased an old jail on the outskirts of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, had it refurbished, and then made preparations to bring her first party of children to Canada. They arrived in October 1869 with the well-publicised blessings ofboth the Archbishop of Canterbury and The Times of London.

A few months later, Annie Macpherson, a Quaker working independently of Rye, brought another party of young children to Ontario. Soon, Louisa Birt of Liverpool (Macpherson’s sister), Thomas Barnardo of London, Leonard Shaw of Manchester, and William Quarrier of Glasgow… to name but a few of the best-known child-savers… were launching their own child-emigration programmes. Before long there was a proliferation of similar programmes, some of the more notable being implemented by the National Children’s Homes, Mr. Fegan’s Homes of Southwark and Westminster, the Middlemore Homesin Birmingham, the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society, and Miss Stirling of Edinburgh. Because Canada was closer to Britain than was Australia or New Zealand, it became the favoured destination for these charges.

Maria Rye eventually placed over 5,000 children, mostly girls, in many parts of Canada and the United States. Problems arose in 1875 when the Doyle Report was released. Mr. Doyle was sent in 1874 to inspect the children sent to Canada by the Unions (workhouses). His report was very negative about Miss Rye’s work, in particular about the lack of inspection after children had been placed, and she did not bring any children to Canada for a few years after the release of the report.

Underlying all these schemes was the activists’ belief that emigration was an effective way to rescue impoverished British children from the poorest and most crowded districts of Britain’s teeming cities. On Canadian farms, far from the temptations and polluted air of city life, their slum protégés would grow into healthy, industrious adults. Or so the thinking went. The long-lived programme eventually came to a halt in 1939, its end hastened not only by the Great Depression and the opposition of the Canadian labour movement but also by a change of thinking onthe part of Canadians and Britons. Both, it seems, could no longer tolerate the idea of philanthropic organisations separating young children from their parents and sending them to work in distant lands, no matter how salubrious the setting.

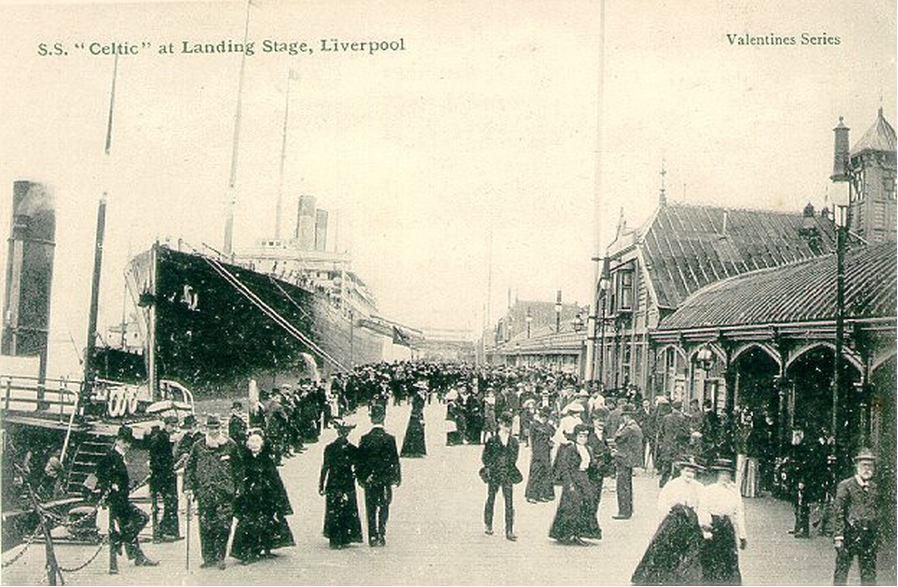

THE PARISIAN

At 4pm on Wednesday 5th April 1882 the SS Parisian let slip from the Great Landing Stage of Liverpool Dock. With a moderate to fresh north wind, it was a fine but cloudy, cold afternoon Captain Wylie headed her into the Irish Sea. On board were 107 cabin passengers, 40 intermediate and902 steerage passengers. Of the 76 children on board, 60 were Miss Rye’s party, 47 of them under 12. Listed among them were Kate, Sarah and Jamie Stewart.

At 4pm on Wednesday 5th April 1882 the SS Parisian let slip from the Great Landing Stage of Liverpool Dock. With a moderate to fresh north wind, it was a fine but cloudy, cold afternoon Captain Wylie headed her into the Irish Sea. On board were 107 cabin passengers, 40 intermediate and902 steerage passengers. Of the 76 children on board, 60 were Miss Rye’s party, 47 of them under 12. Listed among them were Kate, Sarah and Jamie Stewart.

|

By the standards of the day this was a luxurious liner. Having been in service only a year, this single screw steamer made a respectable 14 knots. Amongst the largest liners in the world at 448 feet she was the biggest yet built for the North Atlantic Mail run, the pride of the Allan Line which later became Canadian Pacific. The following day the ship made a brief stop at Queenstown, near Cork, a poignant reminder for the children of their origins. Then on into the Atlantic. At 5,359 tons, the Parisian was the first North Atlantic mail steamer built of steel and the first with bilge keels which stabilised the ship to reduce seasickness. Contrary to modern preconceptions the Allan Line made every effort on behalf of the steerage passengers, who were located on the upper and second passenger decks. |

According to the Allan Line brochure they were ‘supplied with cooked victuals of the best quality. The sanitary arrangements all through the ship are of the most perfect kind. The Company provides the use of a suitable and ample outfit for the voyage, whereby passengers may be saved the trouble, inconvenience, and loss consequent on having to supply their own outfit previous to embarking. The outfit consists of patent life-preserving pillows, mattress, pannikin [tin cup] to hold a pint and a-half, plate, knife, nickel- plated fork, and nickel-plated spoon, and the charge for the use of these articles for the voyage is only a very few shillings.’

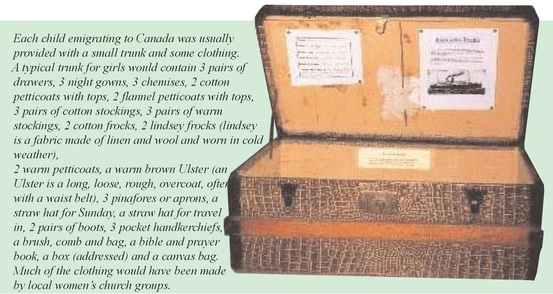

Maria Rye estimated that the cost of emigrating a child to Canada was approximately £15. The Workhouse Guardians paid to Miss Rye approximately £12 for each child that they sent... this was to cover railway fares, passage money, kit, bedding and food etc. The families with whom the children were placed in Canada were not required to pay any fees to Miss Rye.

The Easter holiday was celebrated mid-Atlantic. In fact Kate would have celebrated her birthday too during the trip... if only she'd known the date of her birthday. After another stop at St Johns Newfoundland, the Parisian arrived at Halifax, Nova Scotia at 9am Friday 14th April following a recent snowfall. This was the children's bleak introduction to the New World.

ONTARIO, CANADA

So what awaited the Stewart children? Jamie’s final destination according to his ticket was Halifax itself. Sarah and Kate were destined for Ontario. As Miss Rye only dealt in girls, not boys, it seems that some arrangement had been made for all the children to travel together, at least to Halifax. During this period shiploads of children would arrive at Halifax, Montreal and Quebec City. Most were between the ages of nine and fourteen, but some were much younger; about two-thirds were boys. Once they disembarked, they travelled by train to a distributing home run by the agency that had sent them. In the case of Miss Rye’s children this was at Niagara-on-the-Lake. Children would remain there until final arrangements were made to transport them to their final destination... usually a farm.

So from Halifax the Rye party would have taken the Intercolonial through northern New Brunswick and down the eastern shore of the St. Lawrence river. The remaining train trip, from Montreal to Niagara would have been by the Grand Trunk (possibly stopping at Annie Macphersons childrens' home in Belleville) on to Toronto where they probably stayed overnight in a hostel. Some of the children could have been collected by their new families. The next day they would have travelled on by Great Western of Canada to Niagara-on-the-Lake, with further children being dropped off at stations along the way.

ONTARIO, CANADA

So what awaited the Stewart children? Jamie’s final destination according to his ticket was Halifax itself. Sarah and Kate were destined for Ontario. As Miss Rye only dealt in girls, not boys, it seems that some arrangement had been made for all the children to travel together, at least to Halifax. During this period shiploads of children would arrive at Halifax, Montreal and Quebec City. Most were between the ages of nine and fourteen, but some were much younger; about two-thirds were boys. Once they disembarked, they travelled by train to a distributing home run by the agency that had sent them. In the case of Miss Rye’s children this was at Niagara-on-the-Lake. Children would remain there until final arrangements were made to transport them to their final destination... usually a farm.

So from Halifax the Rye party would have taken the Intercolonial through northern New Brunswick and down the eastern shore of the St. Lawrence river. The remaining train trip, from Montreal to Niagara would have been by the Grand Trunk (possibly stopping at Annie Macphersons childrens' home in Belleville) on to Toronto where they probably stayed overnight in a hostel. Some of the children could have been collected by their new families. The next day they would have travelled on by Great Western of Canada to Niagara-on-the-Lake, with further children being dropped off at stations along the way.

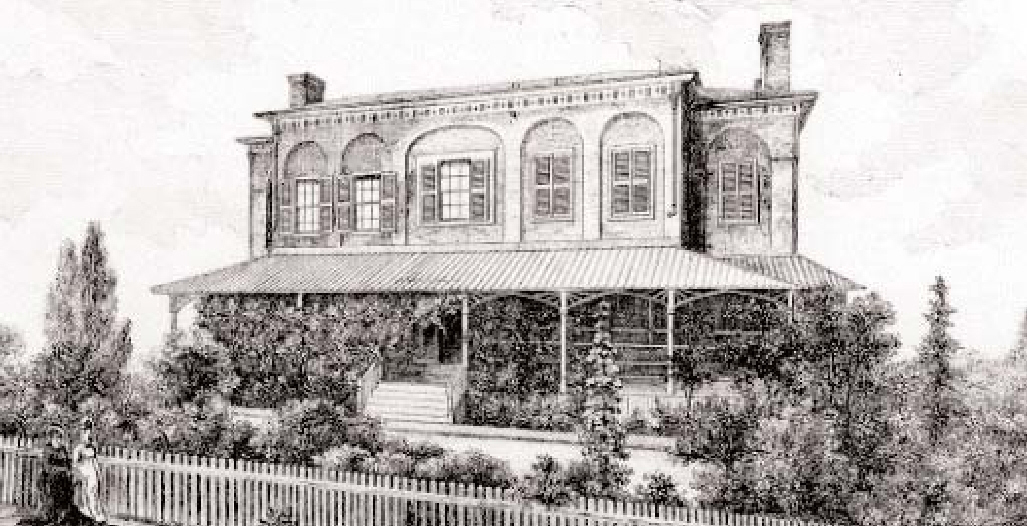

Miss Rye's reception home at Niagara was called 'Our Western Home'. This former jail and courthouse could accommodate up to 120 children.

Newspaper advertisements would alert farmers to anew shipment of children. They would go to the home, size up the children as they would livestock at a market fair, select a child and take him or her home. No attempt was made to keep brothers and sisters together. Rye would line them up in the living room and interested parties would take their pick. She even advertised in the New York and other USA newspapers. In one newspaper account she bragged that she got rid of her girls quickly... within a couple of days. The younger ones were supposed to get training but in reality were not in the home for long enough. There was evidently a school at Our Western Home and a large garden tended by the children. The 1882 Annual Report for Miss Rye’s Emigration Home for Destitute Little Girls referring to Kate and Sarah said tersely: “father dead; mother in the workhouse” and that Kate was adopted by Mrs M.P., London, Ontario; and that Sarah was adopted by Mr. R.T., Farmer, Brussels, Ontario.

Aside from very young children too small to be put to work, home children were not usually adopted in any formal or legal sense. Rather, they were indentured, placed in the care and custody of farm families to whom they were bound by a loose agreement. Therefore the situation of a home child was not always one of being ‘adopted’ as we understand the term today, but rather of being ‘bound’ to the family in the capacity of domestic servant and really not having the privileges of family. Once they turned 18 they were free from the indenture or placement to go out on their own and find their own means and work.It was the responsibility of the guardian until the child reached 15 to provide food, education and religion, and up to age 17 a wage per month in lieu of clothing.

Despite the good intentions of those running the distributing homes, sufficient precautions were not taken to ensure proper care of the children once they left the homes. Applicant farmers were not thoroughly screened as to suitability, and children were not visited regularly by an inspector despite government requirements. More often than not, a farmer’s word that “things are fine” was accepted in lieu of an inspector’s visit and detailed inquiry into a child’s welfare. The homes lost track of many children. The children themselves lost track of brothers and sisters sent to other farms. In adulthood, many lacked birth certificates and had no knowledge of their families or of their medical histories. Some children were treated kindly by farm families and fared well. It seems at least that Kate was oneof these. But the broader experience, as evidenced in written and oral accounts recently gathered from former home children and their descendants, ranged from endless drudgery to outright horror. At the extreme end were children who were physically and psychologically abused in criminal ways, beaten, or inadequately clothed and fed. Few gained an education beyond the minimum government requirements, and not all received even that.

Regardless of their treatment, all were exploited… by governments, by emigration agencies, and by farm families.

Aside from very young children too small to be put to work, home children were not usually adopted in any formal or legal sense. Rather, they were indentured, placed in the care and custody of farm families to whom they were bound by a loose agreement. Therefore the situation of a home child was not always one of being ‘adopted’ as we understand the term today, but rather of being ‘bound’ to the family in the capacity of domestic servant and really not having the privileges of family. Once they turned 18 they were free from the indenture or placement to go out on their own and find their own means and work.It was the responsibility of the guardian until the child reached 15 to provide food, education and religion, and up to age 17 a wage per month in lieu of clothing.

Despite the good intentions of those running the distributing homes, sufficient precautions were not taken to ensure proper care of the children once they left the homes. Applicant farmers were not thoroughly screened as to suitability, and children were not visited regularly by an inspector despite government requirements. More often than not, a farmer’s word that “things are fine” was accepted in lieu of an inspector’s visit and detailed inquiry into a child’s welfare. The homes lost track of many children. The children themselves lost track of brothers and sisters sent to other farms. In adulthood, many lacked birth certificates and had no knowledge of their families or of their medical histories. Some children were treated kindly by farm families and fared well. It seems at least that Kate was oneof these. But the broader experience, as evidenced in written and oral accounts recently gathered from former home children and their descendants, ranged from endless drudgery to outright horror. At the extreme end were children who were physically and psychologically abused in criminal ways, beaten, or inadequately clothed and fed. Few gained an education beyond the minimum government requirements, and not all received even that.

Regardless of their treatment, all were exploited… by governments, by emigration agencies, and by farm families.

Sarah's destination, Brussels, a community in Ontario, was originally called Ainleyville. Despite its Belgian name, the village’s population was largely Scots and Irish. By 1880, the village had a population of 1,000. In its heyday, Brussels had mills of every sort… planing, gristing, flouring, saw-powered by water and steam. The town’s millpond is now a reminder of an industry that once flourished there.

Brussels also had a steam carding mill, a corset factory, a furniture factory, blacksmiths, carriage shops, pump factories, a tannery, a steam flax mill, merchant tailor establishments, milliners, boot and shoe makers, and dress-making establishments. Of the many stores recorded in 1879 were six general stores, five groceries, two hardware stores, four tin and stove stores, four boot and shoe stores, two drug stores, two confectioneries, as well as several butchers and bakers. There were no fewer than five hotels, the grandest of which was the Queen’s Hotel on Main Street. The village was served by two lawyers, three doctors and one dentist. The first school was built in 1864. Another report indicates that a public school was built in 1872 with an addition made five years later. There were five teachers in Brussels in 1888.

Kate’s destination, London, Ontario was a city bursting with modernity in the 1880s. Muddy wagon ruts were replaced by gravel and paving stone roads, a telephone exchange and electrical street lighting were established, several modern steel bridges were thrown across the mighty Thames River, an electric street-car line was created, and regular bathing had become more than a passing fad of the ruling classes. In 1880 this thriving young city was already home to a major psychiatric hospital and the brand new Western University. Supplied by the sweet waters of the Thames, London was the home to the great breweries of Ontario including John Carling’s, John Labbatt’s, and the establishment of John C. Blitz. Just to the South of London, across the Thames River, was the township of Westminster.

Brussels also had a steam carding mill, a corset factory, a furniture factory, blacksmiths, carriage shops, pump factories, a tannery, a steam flax mill, merchant tailor establishments, milliners, boot and shoe makers, and dress-making establishments. Of the many stores recorded in 1879 were six general stores, five groceries, two hardware stores, four tin and stove stores, four boot and shoe stores, two drug stores, two confectioneries, as well as several butchers and bakers. There were no fewer than five hotels, the grandest of which was the Queen’s Hotel on Main Street. The village was served by two lawyers, three doctors and one dentist. The first school was built in 1864. Another report indicates that a public school was built in 1872 with an addition made five years later. There were five teachers in Brussels in 1888.

Kate’s destination, London, Ontario was a city bursting with modernity in the 1880s. Muddy wagon ruts were replaced by gravel and paving stone roads, a telephone exchange and electrical street lighting were established, several modern steel bridges were thrown across the mighty Thames River, an electric street-car line was created, and regular bathing had become more than a passing fad of the ruling classes. In 1880 this thriving young city was already home to a major psychiatric hospital and the brand new Western University. Supplied by the sweet waters of the Thames, London was the home to the great breweries of Ontario including John Carling’s, John Labbatt’s, and the establishment of John C. Blitz. Just to the South of London, across the Thames River, was the township of Westminster.

|

A letter has remained in the possession of the family, written by 13-year old Kate to her 17-year old brother Johnny in England.

|

Westminster Dec 11th 85 (1885)

Dear Brother Johnny, I received your letter & was very pleased to hear from you, & hope you will write again soon & tell me any news of mother & all that you can - I hope you are doing well. I am very well - & very comfortable going to school now again regularly. Mrs. Phillips was very sick along time & I had to stay at home to help her. Next Wednesday is our examination at school. Our teacher is going to leave this Christmas & next year we are to have a gentleman teacher. We had a large party on 3rd November. Mrs.Phillips niece was married here - we had about 50 guests. I had a splendid time. They were married in the evening about half past 8 o'clock. I have a good time. Mrs. Phillips is very kind to me - we have plenty of apples and all kinds of fresh fruit especially raspberries & lots of ducks, chickens,turkeys &c. I help Mrs. Phillips with all kinds ofwork. She wants me to grow up useful. There is a'Home' near here called the 'Guthrie Home'; the children come from Mr. Middlemore's home at Birmingham. One of the girls goes to school with me. I know a girl who came from Miss Ryes some years ago. Now she is grown up & gets 7dollars a month & is such a neat tidy girl I hope I shall be able to get such wages some time. Can you tell me when my birthday is please? I give my love to all & with love I am your affe sister Kate. |

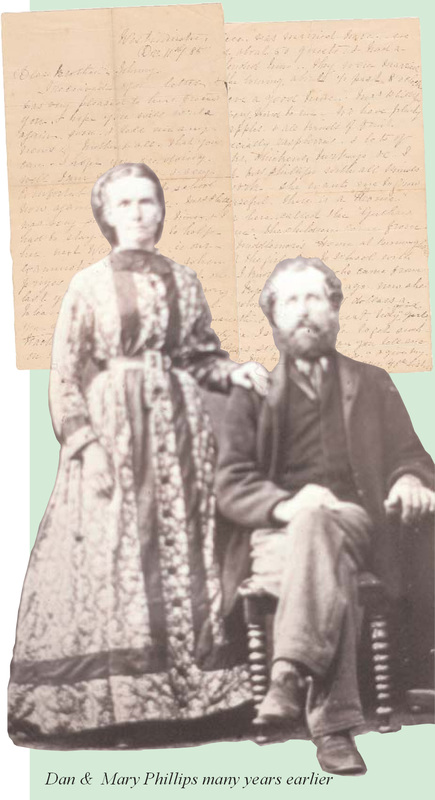

Kate had been adopted by Dan and Mary Phillips, who apparently took on other home children apart from Kate and also ran a boarding house. Dan Dewitt Phillips was 63 in 1882, a Presbyterian farmer of Scottish ancestry. Mary, his 45-year old second wife, was Church of England but of Dutch ancestry. He seems to have owned three farm lots (200 acres each) east of Pond Mills on the north side of what is now Southdale Road (or maybe the north or south side of Commissioners Road to the north of Southdale Road).Dan was developing a terrible skin condition that was eventually to claim his life. His death certificate said, "Died at age 77 years and 5 months of ulcers and slough of face and nose, of 12 years duration".

Kate’s letter contains mention of a wedding celebration, and the London Advertiser, 6th November 1885 carried the following article.“An interesting event occurred on Tuesday evening in Westminster, the occasion being the marriage ofMr. Thomas Flinn to Miss Mary Catherine Hart of Cornwall. The 'Commodore' was supported by Mr. Jas. Dunn.A large number of guests were in attendance, and the presents were numerous and costly. After the ceremony the happy couple left for a trip to the East.”

The Ontario Marriage Register shows that Mary actually lived a few hundred miles away in Cornwall in eastern Ontario. The 1886 London Ontario directory shows a Thomas Flynn, chief attendant at the Asylum or the Insane, resident there. On 4th September 1888 Kate married Dan’s nephew William S Tilton at 168 Adelaide St. London Ontario.They gave their ages as 17 and 25 respectively, though Kate was probably barely 16 and he was definitely31. The witnesses were Thomas and Mary Flynn. The marriage was destined to fail, as a member of the Tilton family had noted of William, “Separated from wife, last seen going west on a boat.” His occupation had been recorded as ‘Labourer’.

Kate headed in the opposite direction, crossing into the United States in 1890. After becoming a naturalised US citizen the following year she married Canadian farm owner Cornelius Sullivan, 17 years her senior, on 10th March 1892. Just three months later on 8th June 1892, she gave birth to James. Her marriage to William Tilton is not mentioned in any further documents, although it could be argued that as she was underage at the time it would not have been legally binding anyway. The Sullivans settled in Brady, Saginaw, Michigan.

A few miles to the east in Birch Run, Saginaw, her sister Sarah married glassblower William Cannon on May 16 1895. This suggests that the two girls had maintained contact in Ontario and crossed over to the United States together.

The Sullivans remained in the Michigan area and had a total of ten children, though not all survived infancy. Cornelius died in 1922 of a long standing kidney inflammation. Three years later Catherine married George H Ransom, a streetcar conductor of the same age with a taste for wedding cake… this was his third marriage and by the time of his death in 1937 he and Kate were divorced.

Sarah and William Cannon had six children but by 1910 only three had survived. He died of a stroke in 1915 a few months after their daughter’s wedding and Sarah, who had been divorced from William, lived in rented property in Toledo City with her two boys and the family all remained in that area for many years.

[Photograph below ] Sarah aged 55