Cecelia JOWETT, her sisters Ethel & Annie, Rose, Violet and her brother Ernest, William and Sydney

An Orillia, Stephen Leacock & Home Child Connection

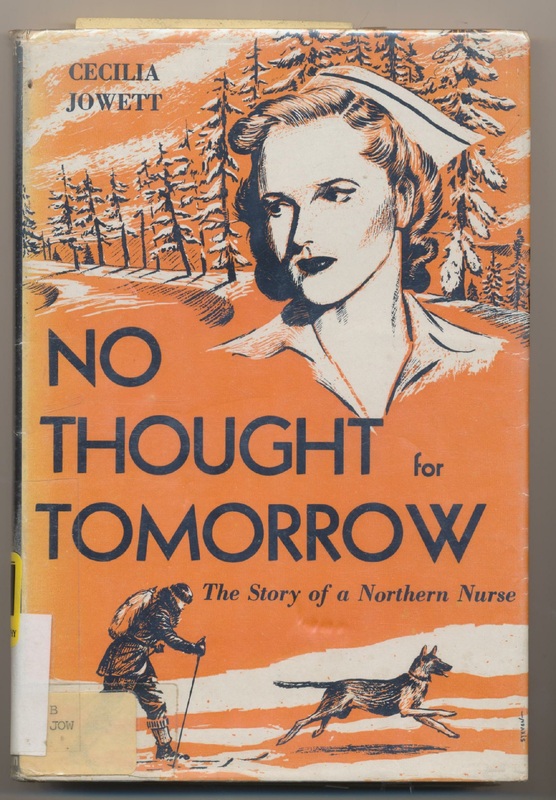

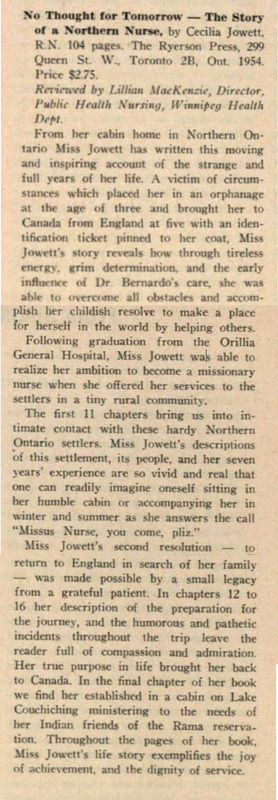

"An English orphanage child is sent to Canada, and dedicates her life to others as a nurse in the Northland."

"Oh, I'd never take a child like that into my home" I have heard ladies say, "You never know how they will turn out." And there I was, a graduate nurse, in their homes, rendering skilled assistance, perhaps saving or helping to save a life. Yet they didn't dream that I was on of "those children" once."

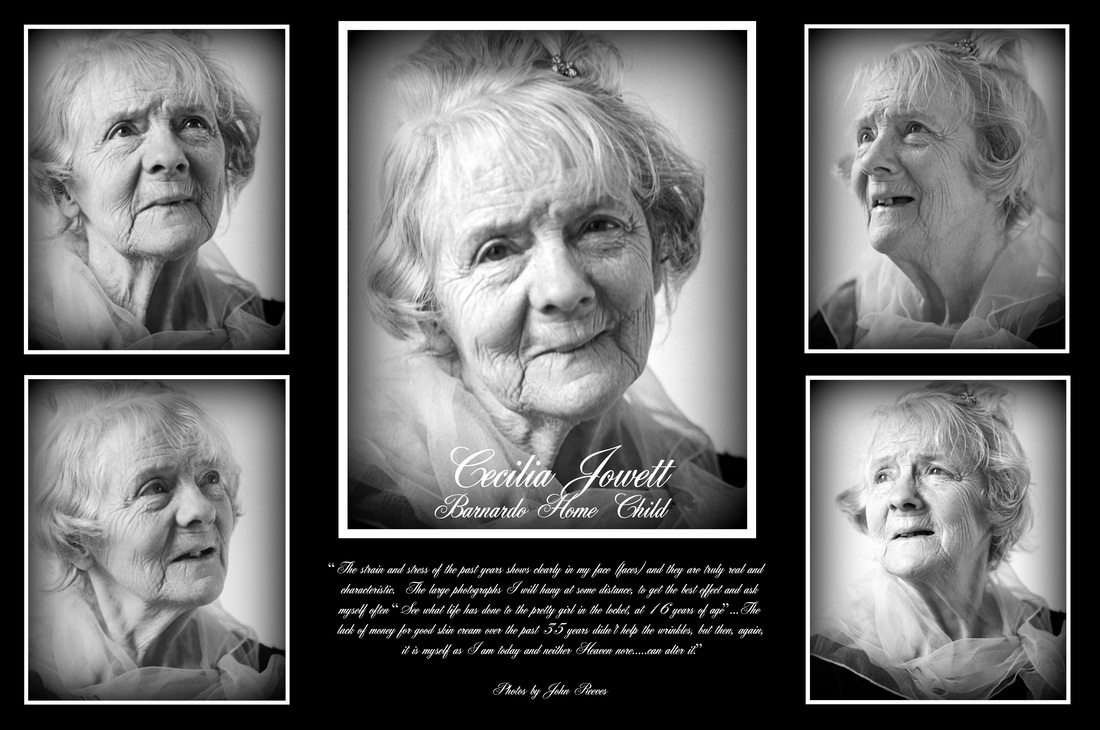

Cecelia taken by John Reeves 1965

From the book "About Face" by John Reeves, quoted with permission:

Cecilia Jowet Author, Photgraphed 1965

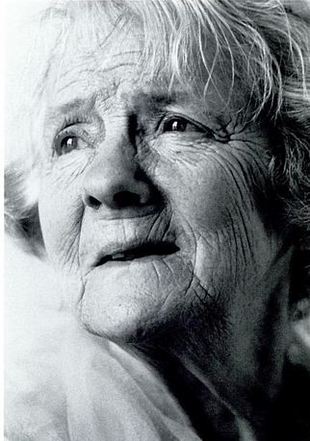

People are seldom at ease with their own portriat. The physical image you create rarely conforms to the mental image they have of themselves. There are, however, exceptions to this rule and Cecilia Jowett was one. Jowett spent the greater part of her life working as a country nurse, first in a pioneer community near Cochrane, and then in Longford Mills, a villiage nine miles north of Orillia, on Lake Couchiching. While living and working in the Orillia she got to know Stephen Leacock, who encouraged her to write about herself.

Jowett's autobiography, No Thought for Tomorrow, was published by Ryerson Press in 1954. Miss Jowett was an old family friend, and when she learned that I had become a photographer, she asked me to produce a portrait of her, which I did in March, 1965. Her poignant response to the pictures I shipped to Longford Mills was unexpected and touching. I quote her letter in part: "The photographs came safely and I do thank you for the honor you have shown me in granting my wish that they are yours, your work, and mean much more to me therefore. One pose, quite unconsciously on my part, is like "Whistler's Mother," so nothing is really new under the sun.

The strain and stress of the past years shows clearly in my face ("faces") and they are truly real and characteristic. The large photographs I will hang at some distance, to get the best effect and ask myself often "See what life has done to the pretty girl in the locket, at 16 years of age"...The lack of money for good skin cream over the past 35 years didn't help the wrinkles, but then, again, it is myself as I am today and neither Heaven nore....can alter it."

Cecilia Jowet Author, Photgraphed 1965

People are seldom at ease with their own portriat. The physical image you create rarely conforms to the mental image they have of themselves. There are, however, exceptions to this rule and Cecilia Jowett was one. Jowett spent the greater part of her life working as a country nurse, first in a pioneer community near Cochrane, and then in Longford Mills, a villiage nine miles north of Orillia, on Lake Couchiching. While living and working in the Orillia she got to know Stephen Leacock, who encouraged her to write about herself.

Jowett's autobiography, No Thought for Tomorrow, was published by Ryerson Press in 1954. Miss Jowett was an old family friend, and when she learned that I had become a photographer, she asked me to produce a portrait of her, which I did in March, 1965. Her poignant response to the pictures I shipped to Longford Mills was unexpected and touching. I quote her letter in part: "The photographs came safely and I do thank you for the honor you have shown me in granting my wish that they are yours, your work, and mean much more to me therefore. One pose, quite unconsciously on my part, is like "Whistler's Mother," so nothing is really new under the sun.

The strain and stress of the past years shows clearly in my face ("faces") and they are truly real and characteristic. The large photographs I will hang at some distance, to get the best effect and ask myself often "See what life has done to the pretty girl in the locket, at 16 years of age"...The lack of money for good skin cream over the past 35 years didn't help the wrinkles, but then, again, it is myself as I am today and neither Heaven nore....can alter it."

The Story of Cecila Jowett

by Lori Oschefski for the book "Bleating of the Lambs"

by Lori Oschefski for the book "Bleating of the Lambs"

"Oh, I'd never take a child like that into my home" I have heard ladies say, "You never know how they will turn out." And there I was, a graduate nurse, in their homes, rendering skilled assistance, perhaps saving or helping to save a life. Yet they didn't dream that I was on of "those children" once." - Cecilia Jowett in her 1954 autobiography “No Thought for Tomorrow - The Story of a Northern Nurse”

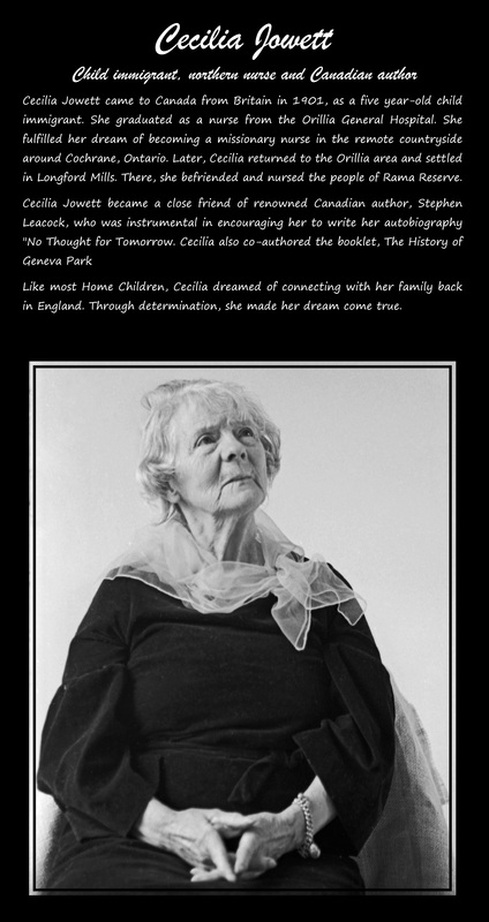

Cecilia Clara Ellen Jowett was born on November 11 1890 in East India Docks, England. She was the fourth child born to parents Seth Jowett and his wife Annie Elizabeth Sarah Sanderson. When Cecilia was three years old the family divided for reasons she never understood. After the separation, she was placed in the Dr. Barnardo Homes in England along with a sister Ethel and brother Ernest. In 1901, Cecilia was shipped to Canada.

Cecilia recalls her childhood feeling of this in her book: “my mind see the lonely little five-year-old girl who came out from England so long ago, with just a ticket pinned to her coat by way of family. She was a small girl, but with a large determination. A strange world lay all about her, and in it she walked alone." She vividly remembered the ocean journey to Canada, the beautiful scintillating icebergs, the whales which surfaced, great green billows of angry water and friendly sea birds. At her journey’s end was the large beautiful gabled home of Hazel Brae in Peterborough. Out of a gable window the St. Nicholls Hospital could be seen and Cecilia would gaze at it longing to become a nurse. After Cecilia’s stay at the Dr. Barnardo Home in England, she vowed to be kind to everyone, as the nurses there had been kind to her. She became determined to become a nurse when she grew up.

The life Cecilia describes at Hazel Brae was a peaceful and idyllic. A haven for the girls who had already suffered in their lives. Cecilia loved to lay under the big linden tree, gazing upward into the sky and dreaming of nothing in particular . She was just happy and content to be at Hazel Brae.

Her next memory she recounts was of the Partridge family farm in Shanty Bay, Ontario. “I can still taste the apples which grew in the orchard of that enchanted farm. It was a good Methodist home. On Sundays a red damask cloth was spread on the table, and we would gather about the cottage organ, Enid and Lexy and I, to sing, ‘Lord, we come in our childhood’s early morning.’” Cecilia developed a deep faith in God which she carried through her life. As content as she described her life on this farm, Cecilia suffered as many Home Children did. The children at school taunted and teased her. “Children can be so cruel and they tormented me because in their eyes I was an orphan.” As a child she would cry every time she heard a train whistle, as its sound only brought back feelings of the separation and the loneliness she had endured. “Our childhood years stay ever with us, and later on, bring back memories that move and shake us when we least expect it”

Cecilia’s second childhood wish was find her family and become part of the world she felt she had ben crowded out of at such an early age. “My beloved mother, for whom I fought for at school, I scarcely remembered.”

Cecilia was able to fulfill her dream of becoming a Nurse. Working during the day and studying at night, she put herself through nursing school, graduating from the Orillia General Hospital. During the flu epidemic in 1918 Cecilia was put in charge of an emergency hospital in Longford Mills, a small village on the south side of Lake Couchiching. It was while working at the Orillia General Hospital that she had nursed the wife of Stephen Leacock, a man who would become a close friend and encouraged her to write. Another man whom she befriended was Count Nicholas Ignatieff. Both men were inspirational influences to Cecilia. Cecilia nursed at some of the top hospitals in Canada. Mt. Sinai, Toronto General, Toronto Sick Kids, and the Hamilton General Hospital where she served as a Special Nurse. In 1930 she returned to Northern Ontario to become a Missionary Nurse. Cecilia’s brother Ernest, who lived there, was not well. He was living in Hunta, Ontario, about seventeen miles from Cochrane. Ernest was a First World War veteran suffering from pleurisy and in need of care. Although Cecilia had four siblings, her brother Ernest is the only one she writes about in her book. Cecilia would spend seven years living in Hunta, eventually building her own cottage there.

She describes Northern Ontario as a place of magic. A place where the cold and fury of winter blizzards cast a spell. “The silence of the North can be heard and felt. The music of the sleigh runners on the moonlit snow is a thing never to be forgotten. One doesn't age in the North for each day is a new adventure, testing one's powers in ways which the more enervating conditions of the South never know.”

During a short trip back to Hamilton, one of her patients gave her a puppy which she name Prince. Cecilia brought Prince to Hunta, living for a short time with Ernest. She felt at last, she had found a home and a family in Ernest. The cabin was old and in the northern cold, the splitting of the wood in the roof and walls could be heard. Cecilia and Ernest were soon beginning to plan the building of a new cottage which she would name Journey’s End. Initially Ernest would reside there with her, but restless and feeling she was encroaching on his bachelor ways, he would move out, leaving Cecilia alone once again.

During her seven years in Hunta, Cecilia nursed for very little money. Her cash receipts were forty dollars for seven years and she accepted near starvation conditions with no complaint. Anything Cecilia had, she gave to those she felt needed it more than her. She skied, walked, paddled or rode a bicycle to visit her patients. Often her pay was nothing more than a loaf of bread, a piece of chicken or ham. One woman paid her with a live hen and a dozen chicks. Those days were tough for Cecilia, she and her dog Prince often went hungry. Her friends in Hamilton often sent care packages to her. During the long evenings Cecilia began to write. Her first article was a letter to the Contributors Column of The Atlantic Monthly magazine. Cecilia would begin a stream of correspondence with a variety of people.

After a former patient passed away leaving Cecilia a bit of money, the desire to reunite with her family surfaced again. A flurry of letters to England enabled her to locate her father. She made the decision to sell Journey’s End and return to England. Cecilia donated her worldly goods, packed up what she and Prince needed and embarked on this next journey in her life.

In England, Cecilia was met by her Father and her Aunt. Cecilia’s joy was dispelled upon learning that her Aunt had not known about Cecilia and her siblings. Cecilia was expecting to stay with family but was taken to a rented room instead. That night the loneliness of the past forty years took its toll on her. She broke down and wept as though her heart would break.

Cecilia enjoyed visiting her family and was hoping to stay permanently in England, however she felt she did not fit well into her father’s life. Cecilia felt it was best to leave him undisturbed. Staying a little shy of two months, she returned to Canada at the end of August 1934.

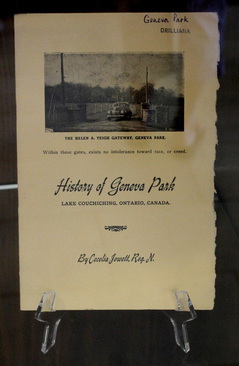

Returning to Canada meant another readjustment in her life. The northern winters had proven to be too difficult for Cecilia and her thoughts turned back to Orillia. Remembering her time in Longford Mills, she decided to settle there. Cecilia would nurse once again for the members of the Ojibway Nations at Rama. Her cottage was located two miles north of Rama, making the community accessible to her. It was while Cecilia was living here that Stephen Leacock, a well know author, befriended her. She would often travel to his home on Couchiching to tend to his gardens. Stephen Leacock encourage Cecilia to write. In 1948 she published a booklet on the history of Geneva Park, a one hundred and fifty acre YMCA facility, located across the street from her Longford Mills home. Geneva Park is still an active conference center today. In 1954 Cecilia published her autobiography, “No Thought for Tomorrow”.

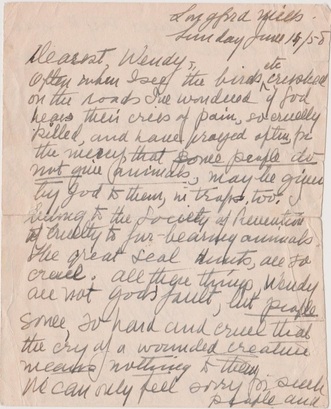

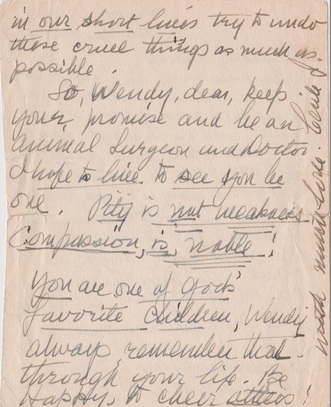

Though out her life, Cecilia touched many people. We are still uncovering people with many fond memories of Cecilia. Wendy Wilson Pearce shares this letter Cecilia wrote her in 1958:

Dearest Wendy

Often when I see the Birds etc crushed on the roads I've wondered if God hears their cries of pain, so cruelly killed and have prayed often for the mercy that some people do not give the animals may be given by God to them, in traps too. I belong to the Society of Prevention of Cruelty to fur bearing animals. The great Seal Hunts all so cruel. All these things Wendy are not Gods fault but People. Some so hard and cruel that the cry of a wounded creature means nothing to them. We can only feel sorry for such people and in our short lives try to undo these cruel things as much as possible. So Wendy Dear keep your promise and be an animal Surgeon and Doctor. I hope to live to see you be one. PITY IS NOT WEAKNESS COMPASSION IS NOBLE. You are one of Gods favorite Children Wendy always remember that through your life be Happy to Cheer others.

With much Love Cecilia Jowett

John Reeves

In 1965, when Cecilia found out that a good friend’s son, John Reeves, had become a photographer, she asked that he take her portrait. In his recent book “About Face”, he published one of the portraits of he had taken of Cecilia. He remarks on her reaction to her portrait, noting that not many people are comfortable with their images, he felt Cecilia was an exception. In a thank you note to John she writes:

“The strain and stress of the past years shows clearly in my face ("faces") and they are truly real and characteristic. The large photographs I will hang at some distance, to get the best effect and ask myself often "See what life has done to the pretty girl in the locket, at 16 years of age"...The lack of money for good skin cream over the past 35 years didn't help the wrinkles, but then, again, it is myself as I am today and neither Heaven nore....can alter it."

What Cecilia kept hidden

In Cecilia’s autobiography she often spoke of the loss of her family. The only sibling mentioned in her book was Ernest. There was no reference to how he arrived in Canada, leading to the speculation that he also was the British Home Child. Cecilia leads us to believe she never saw her mother again. She speaks of Ernest and her reunion with her father. What she does not tell us may very well be more profound than what she did. Her words “My beloved mother, for whom I fought for at school, I scarcely remembered” proved to be delusive.

While researching Cecilia’s story I discovered that, in fact, her mother, Annie and many other siblings Cecilia did not mention, immigrated to Canada and lived in close proximity with her. Cecilia’s parents Seth and Annie, married in 1886 had separated. They had six children, of whom four survived, Ethel, Cecilia, Ernest and Annie. In 1898 her mother Annie would marry for a second time to John Beddow. Two children were born of this union, Rose and Violet. Annie and John are found in the 1901 census living with their two daughters along with Ernest and Annie from her first marriage. Conspicuously missing is Cecilia and Ethel. For reasons unknown, they had been taken in by the Dr. Barnardo Homes. In 1901 were found boarded out with the Stock family in Warminster, Wiltshire, England.

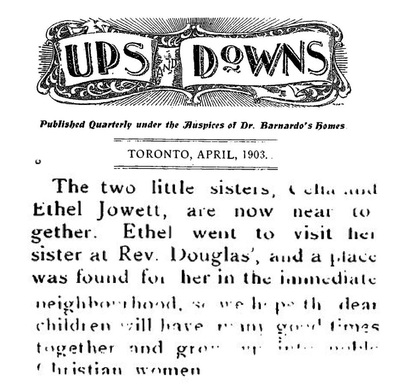

Cecilia does mention that when she arrived in Canada in 1901, her sister Ethel was sent with her. The girls were take to Peterborough together. From there Cecilia was placed, not with the Partridge family in Shanty Bay, but with Reverend Douglas. Ethel’s placement was close enough to Cecilia that the girls were able to visit often.

Virtually on the heels of Cecilia and Ethel’s immigration, their mother Annie arrived in Canada. On the January 1905 immigration record, Annie and children Ernest, Annie, Rose and Violet were all listed under the last name of “Beddows”. Annie was listed first as married, then “widow” was written beside her name. They came to Canada under the care of the Honorable Ellen Lacy, a woman who also brought British Home Children to Canada. Their destination was given as Toronto, Ontario. On October 11, 1905, nine months after their arrival, forty year old Annie married twenty two year old Cornelius John Fine. Cornelius, also from England, had arrived in Canada a few weeks after Annie and the children. John Beddows is found on the 1911 census in Wolverhampton, Staffordshire, working but listed as deaf.

Annie’s third marriage did not last either. Cornelius married Elizabeth Amanda Hackney in York, Ontario in May of 1907. Eventually Cornelius returned to England for good. The 1911 census finds Annie, Ernest, Rose and Violet still living together in Toronto. Annie is still using the last name Fine, but she is listed as single.

The 1921 census finds Annie living in Cochrane, Ontario with Ernest, her daughter Annie and her daughter’s husband and child. Cochrane was the very place Cecilia was headed in 1930, to care for her brother Ernest. The marriage record of Cecilia’s sister Annie to William Bailey in 1913 records the witness to this marriage as their mother Annie Fine and Cecilia herself. With this information Like all British Home Children, Cecilia suffered the humiliation of being essentially abandoned by both her parents. In Canada she was taunted and teased, called an orphan while living with complete strangers and knowing full well that both parents were alive. A child’s mind is unable to process the complex reasons behind a family break-up or the migration process. What Cecilia knew was that her mother did not take her back into the family, but remarried and had more children. Many of our British Home Children invented alternative pasts, they rewrote their own histories, omitting what they could not understand and omitting their pain.

Like all British Home Children, Cecilia suffered the humiliation of being essentially abandoned by both her parents. In Canada she was taunted and teased, called an orphan while living with complete strangers and knowing full well that both parents were alive. A child’s mind is unable to process the complex reasons behind a family break-up or the migration process. What Cecilia knew was that her mother did not take her back into the family, but remarried and had more children. Many of our British Home Children invented alternative pasts, they rewrote their own histories, omitting what they could not understand and omitting their pain.

Lori’s Notes: Cecilia’s special connection to me

I had grown up with the knowledge of the British Home Children but not a complete understanding of their story. It was not taught to us in school and was never mentioned in our home. After discovering my family connections to the BHC, it made me wonder why I knew about them. Upon learning the name of Cecilia’s book “No thought for Tomorrow” in the John Reeve’s book “About Face”, although he did not mention her BHC background, I knew I had read that book and that she indeed was the BHC we were searching for. Seeing her cover for the “first” time that day, brought back my memories of reading this book as a thirteen year old in my parents basement in Orillia. I now distinctly remember my Mother, who was also a Nurse, telling me that she had known Cecilia.

Cecilia Clara Ellen Jowett was born on November 11 1890 in East India Docks, England. She was the fourth child born to parents Seth Jowett and his wife Annie Elizabeth Sarah Sanderson. When Cecilia was three years old the family divided for reasons she never understood. After the separation, she was placed in the Dr. Barnardo Homes in England along with a sister Ethel and brother Ernest. In 1901, Cecilia was shipped to Canada.

Cecilia recalls her childhood feeling of this in her book: “my mind see the lonely little five-year-old girl who came out from England so long ago, with just a ticket pinned to her coat by way of family. She was a small girl, but with a large determination. A strange world lay all about her, and in it she walked alone." She vividly remembered the ocean journey to Canada, the beautiful scintillating icebergs, the whales which surfaced, great green billows of angry water and friendly sea birds. At her journey’s end was the large beautiful gabled home of Hazel Brae in Peterborough. Out of a gable window the St. Nicholls Hospital could be seen and Cecilia would gaze at it longing to become a nurse. After Cecilia’s stay at the Dr. Barnardo Home in England, she vowed to be kind to everyone, as the nurses there had been kind to her. She became determined to become a nurse when she grew up.

The life Cecilia describes at Hazel Brae was a peaceful and idyllic. A haven for the girls who had already suffered in their lives. Cecilia loved to lay under the big linden tree, gazing upward into the sky and dreaming of nothing in particular . She was just happy and content to be at Hazel Brae.

Her next memory she recounts was of the Partridge family farm in Shanty Bay, Ontario. “I can still taste the apples which grew in the orchard of that enchanted farm. It was a good Methodist home. On Sundays a red damask cloth was spread on the table, and we would gather about the cottage organ, Enid and Lexy and I, to sing, ‘Lord, we come in our childhood’s early morning.’” Cecilia developed a deep faith in God which she carried through her life. As content as she described her life on this farm, Cecilia suffered as many Home Children did. The children at school taunted and teased her. “Children can be so cruel and they tormented me because in their eyes I was an orphan.” As a child she would cry every time she heard a train whistle, as its sound only brought back feelings of the separation and the loneliness she had endured. “Our childhood years stay ever with us, and later on, bring back memories that move and shake us when we least expect it”

Cecilia’s second childhood wish was find her family and become part of the world she felt she had ben crowded out of at such an early age. “My beloved mother, for whom I fought for at school, I scarcely remembered.”

Cecilia was able to fulfill her dream of becoming a Nurse. Working during the day and studying at night, she put herself through nursing school, graduating from the Orillia General Hospital. During the flu epidemic in 1918 Cecilia was put in charge of an emergency hospital in Longford Mills, a small village on the south side of Lake Couchiching. It was while working at the Orillia General Hospital that she had nursed the wife of Stephen Leacock, a man who would become a close friend and encouraged her to write. Another man whom she befriended was Count Nicholas Ignatieff. Both men were inspirational influences to Cecilia. Cecilia nursed at some of the top hospitals in Canada. Mt. Sinai, Toronto General, Toronto Sick Kids, and the Hamilton General Hospital where she served as a Special Nurse. In 1930 she returned to Northern Ontario to become a Missionary Nurse. Cecilia’s brother Ernest, who lived there, was not well. He was living in Hunta, Ontario, about seventeen miles from Cochrane. Ernest was a First World War veteran suffering from pleurisy and in need of care. Although Cecilia had four siblings, her brother Ernest is the only one she writes about in her book. Cecilia would spend seven years living in Hunta, eventually building her own cottage there.

She describes Northern Ontario as a place of magic. A place where the cold and fury of winter blizzards cast a spell. “The silence of the North can be heard and felt. The music of the sleigh runners on the moonlit snow is a thing never to be forgotten. One doesn't age in the North for each day is a new adventure, testing one's powers in ways which the more enervating conditions of the South never know.”

During a short trip back to Hamilton, one of her patients gave her a puppy which she name Prince. Cecilia brought Prince to Hunta, living for a short time with Ernest. She felt at last, she had found a home and a family in Ernest. The cabin was old and in the northern cold, the splitting of the wood in the roof and walls could be heard. Cecilia and Ernest were soon beginning to plan the building of a new cottage which she would name Journey’s End. Initially Ernest would reside there with her, but restless and feeling she was encroaching on his bachelor ways, he would move out, leaving Cecilia alone once again.

During her seven years in Hunta, Cecilia nursed for very little money. Her cash receipts were forty dollars for seven years and she accepted near starvation conditions with no complaint. Anything Cecilia had, she gave to those she felt needed it more than her. She skied, walked, paddled or rode a bicycle to visit her patients. Often her pay was nothing more than a loaf of bread, a piece of chicken or ham. One woman paid her with a live hen and a dozen chicks. Those days were tough for Cecilia, she and her dog Prince often went hungry. Her friends in Hamilton often sent care packages to her. During the long evenings Cecilia began to write. Her first article was a letter to the Contributors Column of The Atlantic Monthly magazine. Cecilia would begin a stream of correspondence with a variety of people.

After a former patient passed away leaving Cecilia a bit of money, the desire to reunite with her family surfaced again. A flurry of letters to England enabled her to locate her father. She made the decision to sell Journey’s End and return to England. Cecilia donated her worldly goods, packed up what she and Prince needed and embarked on this next journey in her life.

In England, Cecilia was met by her Father and her Aunt. Cecilia’s joy was dispelled upon learning that her Aunt had not known about Cecilia and her siblings. Cecilia was expecting to stay with family but was taken to a rented room instead. That night the loneliness of the past forty years took its toll on her. She broke down and wept as though her heart would break.

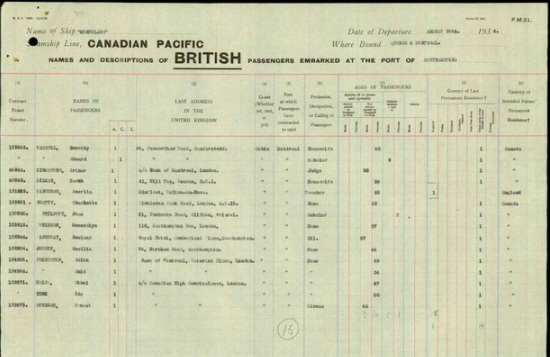

Cecilia enjoyed visiting her family and was hoping to stay permanently in England, however she felt she did not fit well into her father’s life. Cecilia felt it was best to leave him undisturbed. Staying a little shy of two months, she returned to Canada at the end of August 1934.

Returning to Canada meant another readjustment in her life. The northern winters had proven to be too difficult for Cecilia and her thoughts turned back to Orillia. Remembering her time in Longford Mills, she decided to settle there. Cecilia would nurse once again for the members of the Ojibway Nations at Rama. Her cottage was located two miles north of Rama, making the community accessible to her. It was while Cecilia was living here that Stephen Leacock, a well know author, befriended her. She would often travel to his home on Couchiching to tend to his gardens. Stephen Leacock encourage Cecilia to write. In 1948 she published a booklet on the history of Geneva Park, a one hundred and fifty acre YMCA facility, located across the street from her Longford Mills home. Geneva Park is still an active conference center today. In 1954 Cecilia published her autobiography, “No Thought for Tomorrow”.

Though out her life, Cecilia touched many people. We are still uncovering people with many fond memories of Cecilia. Wendy Wilson Pearce shares this letter Cecilia wrote her in 1958:

Dearest Wendy

Often when I see the Birds etc crushed on the roads I've wondered if God hears their cries of pain, so cruelly killed and have prayed often for the mercy that some people do not give the animals may be given by God to them, in traps too. I belong to the Society of Prevention of Cruelty to fur bearing animals. The great Seal Hunts all so cruel. All these things Wendy are not Gods fault but People. Some so hard and cruel that the cry of a wounded creature means nothing to them. We can only feel sorry for such people and in our short lives try to undo these cruel things as much as possible. So Wendy Dear keep your promise and be an animal Surgeon and Doctor. I hope to live to see you be one. PITY IS NOT WEAKNESS COMPASSION IS NOBLE. You are one of Gods favorite Children Wendy always remember that through your life be Happy to Cheer others.

With much Love Cecilia Jowett

John Reeves

In 1965, when Cecilia found out that a good friend’s son, John Reeves, had become a photographer, she asked that he take her portrait. In his recent book “About Face”, he published one of the portraits of he had taken of Cecilia. He remarks on her reaction to her portrait, noting that not many people are comfortable with their images, he felt Cecilia was an exception. In a thank you note to John she writes:

“The strain and stress of the past years shows clearly in my face ("faces") and they are truly real and characteristic. The large photographs I will hang at some distance, to get the best effect and ask myself often "See what life has done to the pretty girl in the locket, at 16 years of age"...The lack of money for good skin cream over the past 35 years didn't help the wrinkles, but then, again, it is myself as I am today and neither Heaven nore....can alter it."

What Cecilia kept hidden

In Cecilia’s autobiography she often spoke of the loss of her family. The only sibling mentioned in her book was Ernest. There was no reference to how he arrived in Canada, leading to the speculation that he also was the British Home Child. Cecilia leads us to believe she never saw her mother again. She speaks of Ernest and her reunion with her father. What she does not tell us may very well be more profound than what she did. Her words “My beloved mother, for whom I fought for at school, I scarcely remembered” proved to be delusive.

While researching Cecilia’s story I discovered that, in fact, her mother, Annie and many other siblings Cecilia did not mention, immigrated to Canada and lived in close proximity with her. Cecilia’s parents Seth and Annie, married in 1886 had separated. They had six children, of whom four survived, Ethel, Cecilia, Ernest and Annie. In 1898 her mother Annie would marry for a second time to John Beddow. Two children were born of this union, Rose and Violet. Annie and John are found in the 1901 census living with their two daughters along with Ernest and Annie from her first marriage. Conspicuously missing is Cecilia and Ethel. For reasons unknown, they had been taken in by the Dr. Barnardo Homes. In 1901 were found boarded out with the Stock family in Warminster, Wiltshire, England.

Cecilia does mention that when she arrived in Canada in 1901, her sister Ethel was sent with her. The girls were take to Peterborough together. From there Cecilia was placed, not with the Partridge family in Shanty Bay, but with Reverend Douglas. Ethel’s placement was close enough to Cecilia that the girls were able to visit often.

Virtually on the heels of Cecilia and Ethel’s immigration, their mother Annie arrived in Canada. On the January 1905 immigration record, Annie and children Ernest, Annie, Rose and Violet were all listed under the last name of “Beddows”. Annie was listed first as married, then “widow” was written beside her name. They came to Canada under the care of the Honorable Ellen Lacy, a woman who also brought British Home Children to Canada. Their destination was given as Toronto, Ontario. On October 11, 1905, nine months after their arrival, forty year old Annie married twenty two year old Cornelius John Fine. Cornelius, also from England, had arrived in Canada a few weeks after Annie and the children. John Beddows is found on the 1911 census in Wolverhampton, Staffordshire, working but listed as deaf.

Annie’s third marriage did not last either. Cornelius married Elizabeth Amanda Hackney in York, Ontario in May of 1907. Eventually Cornelius returned to England for good. The 1911 census finds Annie, Ernest, Rose and Violet still living together in Toronto. Annie is still using the last name Fine, but she is listed as single.

The 1921 census finds Annie living in Cochrane, Ontario with Ernest, her daughter Annie and her daughter’s husband and child. Cochrane was the very place Cecilia was headed in 1930, to care for her brother Ernest. The marriage record of Cecilia’s sister Annie to William Bailey in 1913 records the witness to this marriage as their mother Annie Fine and Cecilia herself. With this information Like all British Home Children, Cecilia suffered the humiliation of being essentially abandoned by both her parents. In Canada she was taunted and teased, called an orphan while living with complete strangers and knowing full well that both parents were alive. A child’s mind is unable to process the complex reasons behind a family break-up or the migration process. What Cecilia knew was that her mother did not take her back into the family, but remarried and had more children. Many of our British Home Children invented alternative pasts, they rewrote their own histories, omitting what they could not understand and omitting their pain.

Like all British Home Children, Cecilia suffered the humiliation of being essentially abandoned by both her parents. In Canada she was taunted and teased, called an orphan while living with complete strangers and knowing full well that both parents were alive. A child’s mind is unable to process the complex reasons behind a family break-up or the migration process. What Cecilia knew was that her mother did not take her back into the family, but remarried and had more children. Many of our British Home Children invented alternative pasts, they rewrote their own histories, omitting what they could not understand and omitting their pain.

Lori’s Notes: Cecilia’s special connection to me

I had grown up with the knowledge of the British Home Children but not a complete understanding of their story. It was not taught to us in school and was never mentioned in our home. After discovering my family connections to the BHC, it made me wonder why I knew about them. Upon learning the name of Cecilia’s book “No thought for Tomorrow” in the John Reeve’s book “About Face”, although he did not mention her BHC background, I knew I had read that book and that she indeed was the BHC we were searching for. Seeing her cover for the “first” time that day, brought back my memories of reading this book as a thirteen year old in my parents basement in Orillia. I now distinctly remember my Mother, who was also a Nurse, telling me that she had known Cecilia.

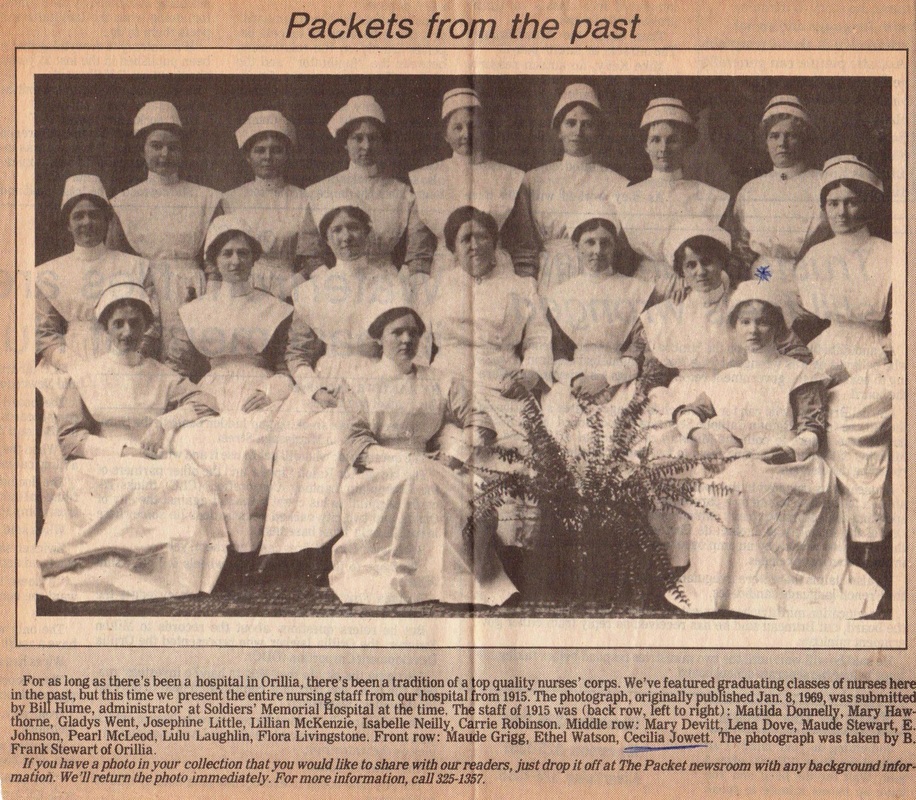

The 1915 staff of the Orillia General Hospital

Matilda Donnelly, Mary Hawthorne, Gladys West, Josephine Little, Lillian McKenzie, Isabelle Nelly, Carrie Robinson, Mary Devitt, Lena Dove, Maude Stewart, E. Johnson, Pearl McLeod, Lula Laughlin, Flora Livingstone, Maude Grigg, Ethel Watson and Cecilia Jowett.

Read Cecilia's book here, No Thought For Tomorrow, the Story of a Northern Nurse

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Download her book here!

| no_thought_for_tomorrow.pdf | |

| File Size: | 95205 kb |

| File Type: | |

A letter and note of remembrance from Wendy Wilson Pearce

July 13 2013

It is so nice to bring back memories of a person that touched my life in an unforgettable way. When I first met Ms Jowett I would have been only about 9 years old..I had a great curiosity towards older people and people in general. she was different very unique and shared care and interest in a young persons interests and thoughts. I loved visiting her and I did for quite some time. I would watch her in her garden she loved flowers and she loved animals as I did and still do. She would share stories of her life and love of nature. One day I was at the cottage with my Mother outside and we looked and here she was coming down our driveway pulling a wagon full of flowers....she said she wanted to give them to my beautiful mother..She was wearing a big sun bonnet and some kind of dress I can see her in my mind to this day. She was I would say eccentric and maybe caught up in her own world if you know what I mean. I lost touch with her as I grew older. I have to this day a hand written letter from her and a old photo that was in the packet when she was a young nurse. She had said she was writing a second book I would love to know if it ever was published. If you would like to see this letter or photo I would gladly share them with you. This is truly a wonderful Happening after all these years.

|

This note was sent to Wendy Wilson Pearce in 1958

Dearest Wendy Sunday June14/58 Often when I see the Birds etc crushed on the roads I've wondered if God hears their cries of pain, so cruelly killed and have prayed often for the mercy that some people do not give the animals may be given by God to them, in traps too. I belong to the Society of Prevention of Cruelty to fur bearing animals. The great Seal Hunts all so cruel. All these things Wendy are not Gods fault but People. Some so hard and cruel that the cry of a wounded creature means nothing to them.We can only feel sorry for such people and in our short lives try to undo these cruel things as much as possible. So Wendy Dear kee your promise and be an animal Surgeon and Doctor. I hope to live to see you be one. PITY IS NOT WEAKNESS COMPASSION IS NOBLE. You are one of Gods favorite Children Wendy always remember that through your life be Happy to Cheer others. With much Love Cecilia Jowett |

Excerpts from

"No Thought for Tomorrow: The Story of a Northern Nurse"

When I was five years old I was brought out to Canada from England, with a ticket pinned to my coat, and with the resolve already in my childish heart that some day I would make a place for myself in the great, cold world, where I could help others as the kind nurses had helped me.

"Oh, I'd never take a child like that into my home" I have heard ladies say, "You never know how they will turn out." And there I was, a graduate nurse, in their homes, rendering skilled assistance, perhaps saving or helping to save a life. Yet they didn't dream that I was on of "those children" once."

"Oh, I'd never take a child like that into my home" I have heard ladies say, "You never know how they will turn out." And there I was, a graduate nurse, in their homes, rendering skilled assistance, perhaps saving or helping to save a life. Yet they didn't dream that I was on of "those children" once."

Excerpt from "The Canadian Nurse"

http://ia600607.us.archive.org/3/items/canadiannurse071955cana/CnVol.51No7July1955.pdf

Name:Cecilia JOWETTDate of departure:3 September 1934Port of departure:SouthamptonPassenger destination port:Montreal, CanadaPassenger destination:Montreal, CanadaDate of Birth:1890 (calculated from age)Age:44Marital status:Sex:FemaleOccupation:NonePassenger recorded on:Page 3 of 14Ship:Official Number:Master's name:Steamship Line:Where bound:Square feet:Registered tonnage:Passengers on voyage:MONTCLARE145964M F MurrayCanadian PacificMontreal, Canada76429724294

Cyril Fry from Gravenhurst remembers his encounter with Cecilia Jowett

from the Orillia Public Library British Home Child Event

April 15, 2013

During the 1930s, organizations were formed in several European countries, followed by Canada and the U.S., to provide cheap overnight accommodations for young people who were prepared to hike, cycle, row or paddle in order to travel and extend their knowledge of the world. For extended trips, travel on public transport was also OK.

The Canadian Youth Hostels Association was one of these. It was founded by two ladies in the Calgary area, whose initiative led to extensions in other provinces, including Ontario and Quebec.

Members paid an annual fee of one dollar if my memory is accurate. There was no age limit in Canada, You wrote ahead, or telephoned, but long distance was something you used rarely in those days. You arrived at the hostel, and paid 25 cents per person for an overnight. There were cooking and washing facilities, usually a kerosene stove, and possibly a shower. The owner of the premises was known as the "Houseparent", and some of these were willing to provide meals, if booked ahead. I believe there was a standard charge, about $1.25.

In 1942, poliomyelitis was epidemic in much of Canada, including Ontario. The most likely period for infection from another person was in summer and fall, and young people were most vulnerable. In fact the term "polio" wasn’t used until later. The disease was known as "infantile paralysis". Children were urged not to attend large gatherings, and for a couple of years, instead of schools opening the day after Labor Day, the first few weeks were cancelled.

Thus it was that year, so a friend, Donald Courtnage, who was about my age, 16, and I decided to cycle through Algonquin Park and on to Ottawa, using Youth Hostels where available, since we were active members of CYH in Brantford, Ontario.

On our second night, we found our way to Longford Mills, where we had booked to stay with Miss Jowett. She was a slim lady with a quiet voice and a German shepherd dog (which we called a "police dog" in those days). Her house was quite small, on the east side of Lake Couchiching. Almost across the road was the entrance to Geneva Park. She had a flower garden, and when we left the next morning, we noticed a tiny community just north, called Floral Park.

The hostel accommodation was in a cabin separate from her house. There was another young chap there the night we stayed, and I think she provided our supper, but I’m not certain of this.

Because we came from Brantford, we were familiar with the Six Nations tribes of Iroquois Indians, as First Nations people were universally known at the time. For that reason we were interested to come through the Rama Reserve en route Longford. As on most reserves of the period, housing was mostly ramshackle, and people’s clothing looked worn. However, the depression had produced similar appearances for a very large percentage of the population over the previous decade, so contrast between the Rama folks and their neighbors was not as obvious as one might expect.

Miss Jowett told us that she had come from England as a little girl and that she had become a nurse. She did not work at the hospital, but visited homes. These included people in Rama, for whom medical facilities were scarce. She told us about the many tourists who came to Geneva Park and other resorts on Lake Couchiching.

We had good weather, and set off again fairly early the next morning. We probably made our own breakfast, because we carried cereal, bread and jam with us, and bought milk as we travelled.

That is the extent of my acquaintance with Miss Jowett, but I’ll add a couple of things which you may find of interest, even though only the first involves her..

Several decades ago, when my wife’s parents were considering a move to a retirement home, we visited Balmoral Lodge, on Sparrow Lake. It was a rather sparse domain, but it provided accommodation less expensively than many others, so it had considerable custom. When we were conducted into the Common Room, a number of residents were sitting in the armchairs, and I realised I recognized one of them. I was sure it was Miss Jowett, the Longford Mills Youth Hostel houseparent. My wife, Marion, who had also stayed in her Youth Hostel, agreed. Unfortunately, Miss Jowett was asleep, and did not wake up before we left, so we missed the opportunity to renew our acquaintance, and not many months later, I saw a Death Notice for her.

Now, the other recollection. In 1944, I had completed my first year at the University of Toronto, and for a week during the summer, my parents had rented a small cottage on Peninsula Lake, east of Huntsville. A passenger boat left Huntsville each morning, came through Fairy Lake and a small canal into Pen Lake and stopped at the North Portage dock. A narrow gauge railway climbed the hill from this dock and travelled about two kilometres to a dock at South Portage on Lake of Bays. The railway, known as The Portage Flyer, was billed as "The World’s Shortest Railway". The engines and a car or two continue to operate in Huntsville.

From South Portage, another boat offered cruises to Bigwin Island, where a well known resort operated, and on to Dorset. The whole process was repeated in the afternoon to return all the passengers to their starting points.

My parents had decided that we should take the train and cruise from North Portage while we were at the cottage, so we were already on the train when the boat arrived one morning. I noticed two young ladies getting off the boat, one of whom was wearing a CYH emblem on her shorts. After the Flyer arrived in South Portage, I asked the girls if they were members of the Youth Hostel Association. They were. One was from Kitchener, the other from Toronto, and they had cycled from Toronto, stopping first at a hostel near Schomberg, then at Longford Mills, and had stayed the night before in the Huntsville hostel.

The one wearing the CYH badge told me that she was to begin an Occupational Therapy course at the University of Toronto in September. I told her that I was the Editor of the CYH Newsletter and asked if she would be interested in helping put issues in envelopes, write the addresses and put on the stamps. She thought she might be, and told me her name.

Back in Toronto that fall, I realized that I remembered her first name, Marion, but couldn’t remember her last name. However, I met another first year OT from Kitchener, and asked if she knew a classmate from her city named Marion. She didn’t, but she said "I’ll ask around" and within a couple of days I had the phone number of Marion’s aunt, with whom she was staying. So, I phoned and she agreed to take the streetcar down to Union Station where the CYH had a small office. This is where the newsletters were prepared for mailing.

I invited Marion to attend Hart House concerts with me, which were free, and she did so. We got to know one another quite well. Hers was a two year course so she graduated in 1946, and I a year later. The year after that, 1948, we were married. We still are, almost 65 years later. We came to Gravenhurst in 1951, after youth hostelling in Ontario, the US, and for two months, around Europe. Here we have raised two girls and a boy, who have done their own travelling and now live in places starting with A, namely Aurora, Alberta and Australia.

The Canadian Youth Hostels Association was one of these. It was founded by two ladies in the Calgary area, whose initiative led to extensions in other provinces, including Ontario and Quebec.

Members paid an annual fee of one dollar if my memory is accurate. There was no age limit in Canada, You wrote ahead, or telephoned, but long distance was something you used rarely in those days. You arrived at the hostel, and paid 25 cents per person for an overnight. There were cooking and washing facilities, usually a kerosene stove, and possibly a shower. The owner of the premises was known as the "Houseparent", and some of these were willing to provide meals, if booked ahead. I believe there was a standard charge, about $1.25.

In 1942, poliomyelitis was epidemic in much of Canada, including Ontario. The most likely period for infection from another person was in summer and fall, and young people were most vulnerable. In fact the term "polio" wasn’t used until later. The disease was known as "infantile paralysis". Children were urged not to attend large gatherings, and for a couple of years, instead of schools opening the day after Labor Day, the first few weeks were cancelled.

Thus it was that year, so a friend, Donald Courtnage, who was about my age, 16, and I decided to cycle through Algonquin Park and on to Ottawa, using Youth Hostels where available, since we were active members of CYH in Brantford, Ontario.

On our second night, we found our way to Longford Mills, where we had booked to stay with Miss Jowett. She was a slim lady with a quiet voice and a German shepherd dog (which we called a "police dog" in those days). Her house was quite small, on the east side of Lake Couchiching. Almost across the road was the entrance to Geneva Park. She had a flower garden, and when we left the next morning, we noticed a tiny community just north, called Floral Park.

The hostel accommodation was in a cabin separate from her house. There was another young chap there the night we stayed, and I think she provided our supper, but I’m not certain of this.

Because we came from Brantford, we were familiar with the Six Nations tribes of Iroquois Indians, as First Nations people were universally known at the time. For that reason we were interested to come through the Rama Reserve en route Longford. As on most reserves of the period, housing was mostly ramshackle, and people’s clothing looked worn. However, the depression had produced similar appearances for a very large percentage of the population over the previous decade, so contrast between the Rama folks and their neighbors was not as obvious as one might expect.

Miss Jowett told us that she had come from England as a little girl and that she had become a nurse. She did not work at the hospital, but visited homes. These included people in Rama, for whom medical facilities were scarce. She told us about the many tourists who came to Geneva Park and other resorts on Lake Couchiching.

We had good weather, and set off again fairly early the next morning. We probably made our own breakfast, because we carried cereal, bread and jam with us, and bought milk as we travelled.

That is the extent of my acquaintance with Miss Jowett, but I’ll add a couple of things which you may find of interest, even though only the first involves her..

Several decades ago, when my wife’s parents were considering a move to a retirement home, we visited Balmoral Lodge, on Sparrow Lake. It was a rather sparse domain, but it provided accommodation less expensively than many others, so it had considerable custom. When we were conducted into the Common Room, a number of residents were sitting in the armchairs, and I realised I recognized one of them. I was sure it was Miss Jowett, the Longford Mills Youth Hostel houseparent. My wife, Marion, who had also stayed in her Youth Hostel, agreed. Unfortunately, Miss Jowett was asleep, and did not wake up before we left, so we missed the opportunity to renew our acquaintance, and not many months later, I saw a Death Notice for her.

Now, the other recollection. In 1944, I had completed my first year at the University of Toronto, and for a week during the summer, my parents had rented a small cottage on Peninsula Lake, east of Huntsville. A passenger boat left Huntsville each morning, came through Fairy Lake and a small canal into Pen Lake and stopped at the North Portage dock. A narrow gauge railway climbed the hill from this dock and travelled about two kilometres to a dock at South Portage on Lake of Bays. The railway, known as The Portage Flyer, was billed as "The World’s Shortest Railway". The engines and a car or two continue to operate in Huntsville.

From South Portage, another boat offered cruises to Bigwin Island, where a well known resort operated, and on to Dorset. The whole process was repeated in the afternoon to return all the passengers to their starting points.

My parents had decided that we should take the train and cruise from North Portage while we were at the cottage, so we were already on the train when the boat arrived one morning. I noticed two young ladies getting off the boat, one of whom was wearing a CYH emblem on her shorts. After the Flyer arrived in South Portage, I asked the girls if they were members of the Youth Hostel Association. They were. One was from Kitchener, the other from Toronto, and they had cycled from Toronto, stopping first at a hostel near Schomberg, then at Longford Mills, and had stayed the night before in the Huntsville hostel.

The one wearing the CYH badge told me that she was to begin an Occupational Therapy course at the University of Toronto in September. I told her that I was the Editor of the CYH Newsletter and asked if she would be interested in helping put issues in envelopes, write the addresses and put on the stamps. She thought she might be, and told me her name.

Back in Toronto that fall, I realized that I remembered her first name, Marion, but couldn’t remember her last name. However, I met another first year OT from Kitchener, and asked if she knew a classmate from her city named Marion. She didn’t, but she said "I’ll ask around" and within a couple of days I had the phone number of Marion’s aunt, with whom she was staying. So, I phoned and she agreed to take the streetcar down to Union Station where the CYH had a small office. This is where the newsletters were prepared for mailing.

I invited Marion to attend Hart House concerts with me, which were free, and she did so. We got to know one another quite well. Hers was a two year course so she graduated in 1946, and I a year later. The year after that, 1948, we were married. We still are, almost 65 years later. We came to Gravenhurst in 1951, after youth hostelling in Ontario, the US, and for two months, around Europe. Here we have raised two girls and a boy, who have done their own travelling and now live in places starting with A, namely Aurora, Alberta and Australia.